The Gulf Stream, which keeps winters in north-west Europe warmer than they could be, is slowing down faster than it ever has during the past 1,000 years. Since 1970, the slowdown has been more accentuated, researchers say. If it continues slowing it could eventually collapse.

Does this mean that countries in north west Europe, including the United Kingdom, will freeze over in winters to come?

Probably not, but the warming effects of climate change will likely be partially offset, scientists involved in a study led by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research believe.

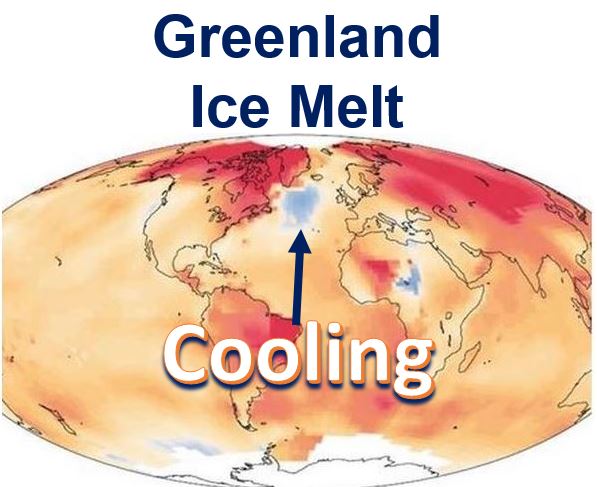

Just above the arrow, below Greenland, you can see a large blue area of sea, that is where the water is cooling. (NASA GISS warming map 1901-2013)

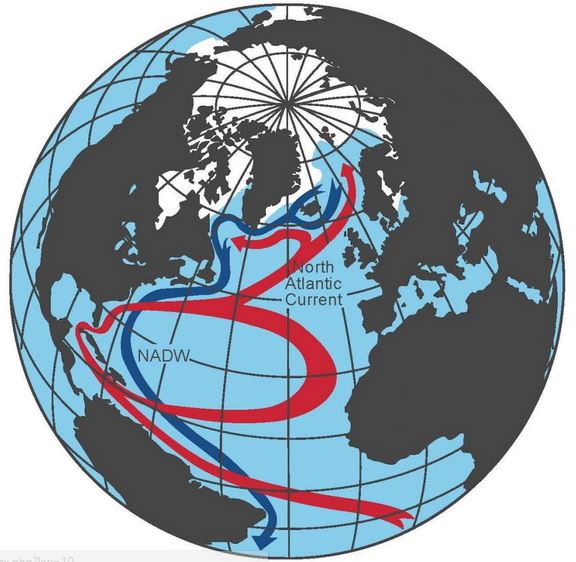

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

There are two major flows of water in the Atlantic Ocean, referred by scientists at the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (Atlantic Overturning).

There is a northward flow, that originates at the tip of Florida, of warm, salty water to the upper layers of the Ocean (this is the Gulf Stream), and another south-moving flow of colder water in the deep Atlantic. Atlantic overturning is a major component of our planet’s climate system.

Over the last 100 years, Atlantic overturning has slowed down by between 15% and 20%. Since 1970, this rate of deceleration has intensified, the researchers wrote in the journal Nature Climate Change.

This slowdown is likely largely caused by the gradual melting of the Greenland ice sheet, which is occurring due to man-made climate change. The ice sheet is melting at a progressively faster pace, the authors wrote.

Eastern North America and North West Europe will be affected

If these Atlantic currents continue to weaken, which looks likely, the weather systems in parts of Europe and North America, as well as sea levels and marine ecosystems will be affected, the authors warn.

Lead study author, Professor of Physics Stefan Rahmstorf, said:

“It is conspicuous that one specific area in the North Atlantic has been cooling in the past hundred years while the rest of the world heats up.”

Previous studies have pointed to the melting of Greenland’s ice as the cause of the Atlantic overturning slowdown.

Mr. Rahmstorf explained:

“Now we have detected strong evidence that the global conveyor has indeed been weakening in the past hundred years, particularly since 1970.”

This illustration shows the movements of currents in the Atlantic Ocean – a graph of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. (Image: Stefan Rahmstorf/PIK)

Given that they had no available data on direct ocean current measurements, Rahmstorf and colleagues used atmospheric and sea-surface temperature data to derive information about the currents in the Atlantic Ocean, exploiting the fact that the Ocean’s currents are the main cause of temperature differences in the sub-polar north Atlantic.

It is possible to reconstruct temperatures going back 1,000 years by gathering data from ice cores, coral, ocean and lake sediments, and tree rings.

The scientists found that changes since 900 AD are “unprecedented”, and believe they are caused by human-induced global warming.

Greenland’s ice melt likely affecting circulation

For currents to occur, parts of the ocean must have different densities. Warm water from the south, which is less dense and lighter, flows northward, while denser, colder water sinks deeper and flows southward.

Jason Box, who works at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, said “Now freshwater coming off the melting Greenland ice sheet is likely disturbing the circulation.”

Greenland’s ice sheet is frozen fresh water. As it melts and pours fresh water into the sea it reduces the salinity of the sea water. Less saline water has a lower density and is less likely to sink.

Mr. Box explains:

“So the human-caused mass loss of the Greenland ice sheet appears to be slowing down the Atlantic overturning – and this effect might increase if temperatures are allowed to rise further.”

Computer climate simulations have underestimated how much fresh water is flowing out of Greenland into the sea, according to data from observations.

Michael Mann, Distinguished Professor of Meteorology at Pennsylvania State University, said:

“Common climate models are underestimating the change we’re facing, either because the Atlantic overturning is too stable in the models or because they don’t properly account for Greenland ice sheet melt, or both.”

“That is another example where observations suggest that climate model predictions are in some respects still overly conservative when it comes to the pace at which certain aspects of climate change are proceeding.”

A new Ice Age? No, but it won’t be nice

As the Gulf Stream weakens the Northern Atlantic will cool. However, its impact will only marginally offset the warming effects of global climate change.

We are not facing another Ice Age, the scientists assure. “Thus the imagery of the ten-year-old Hollywood blockbuster ‘The Day After Tomorrow’ is far from reality,” they said.

However, any change in the circulation of the waters in the Atlantic Ocean will have considerably negative effects on the climate.

Prof. Rahmstorf said:

“If the slowdown of the Atlantic overturning continues, the impacts might be substantial. Disturbing the circulation will likely have a negative effect on the ocean ecosystem, and thereby fisheries and the associated livelihoods of many people in coastal areas.”

“A slowdown also adds to the regional sea-level rise affecting cities like New York and Boston. Finally, temperature changes in that region can also influence weather systems on both sides of the Atlantic, in North America as well as Europe.”

If the currents slow down too much they could collapse and disappear completely. Scientists have long considered that the Atlantic overturning could be a tipping element in the Earth System.

If it all stopped it would be irreversible and there would be nothing we could do about it.

According to an IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) estimate, there is a 1-in-10 chance this could happen this century. Some scientists say the risk is much greater.

Reference: “Evidence for an exceptional 20th-Century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning,” Rahmstorf, S., Box, J., Feulner, G., Mann, M., Robinson, A., Rutherford, S. and Schaffernicht, E. Nature Climate Change. Published 23 March, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/nclimate2554.

Video – Atlantic Ocean Currents

This NASA animation starts off by depicting thermohaline surface flows over surface density, and shows how water sinks in the dense ocean near Greenland and Iceland. The surface of the ocean then fades away and the animation pulls back to show the global thermohaline circulation.