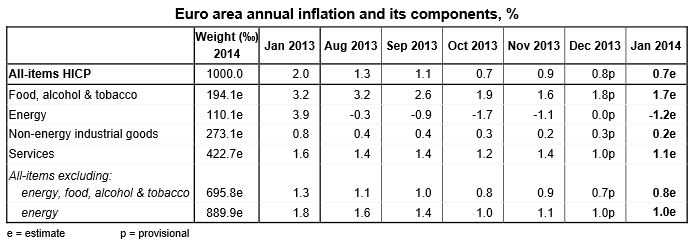

Eurozone deflation fears increased today after Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical agency, published figures showing that inflation dropped to 0.7% in January, compared to December’s 0.8%, moving further away from the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) target of 2%.

Economists had predicted a slightly higher inflation rate for January compared to December, not a fall. Inflation last fell by 0.7% in October 2013, which had been the lowest reading in nearly four years.

Calls are growing throughout the euro area for the European Central Bank (ECB) to take action to protect the region’s fragile economic recovery. If the area suffers deflation, economic growth would probably grind to a halt, and there would be a serious risk of a Japanese style long-lasting period of stagnation.

While the cost of tobacco, alcohol and food increased by 1.7%, energy costs declined by 1.2%.

(Source: Eurostat)

Why is deflation bad?

People with memories of the 1970s’ style runaway inflation may wonder why deflation is a bad thing. Deflation can harm an economy and push it into a long period of no growth or contraction.

People expect prices to fall – if consumers expect falling prices they become more reluctant to spend now, and less willing to borrow. Even simply just having cash and waiting is a good investment because after time has passed you can buy more things with that same amount of money.

If people and businesses spend less and don’t borrow, reaching full employment becomes much more difficult.

A deflationary trap ensues, with the economy staying depressed because people expect falling prices and do not spend, which further slows the economy down and pushes prices into a further downward spiral.

The position of debtors and creditors worsens – people who owe money (debtors) see an increasing burden of their debts if prices fall. In a deflationary environment prices fall, and so do wages, meaning if you have a mortgage for example, your monthly premiums gradually make up a higher percentage of your income, i.e. your debt burden grows.

A growing debt burden forces consumers to spend less, and borrow less, which forces prices further down and reduces the business for creditors (mostly banks). Put simply, a rising debt burden reduces spending, which further exacerbates deflation.

Eurozone deflation fears recently increased

Concerns about deflation in the European Union, particularly within the euro area, i.e. the 18 countries that use the euro as their national currency, have grown during the last few months.

Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), warned at the World Economic Forum last week that Eurozone inflation was “way below” the ECB target of 2%. She urged leaders not to ignore the risk to the bloc’s fragile economic recovery. Lagarde also warned about a global deflation risk in a speed at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. earlier this month.

ECB President, Mario Draghi, said he was confident Eurozone inflation will eventually return to target after a couple of years, even though it is currently subdued and is “expected to remain subdued.” He emphasized that the ECB will do whatever is necessary to prevent deflation.

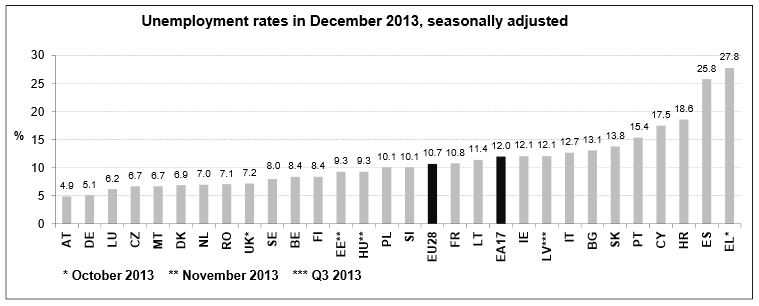

Eurozone unemployment still too high

Eurostat also revealed that unemployment in the euro area was 12% in December, unchanged from the month before.

Meaning of some abbreviations: Germany (DE), Estonia (EE), Greece (EL), Spain (ES), Croatia (HR), Slovenia (SI), Slovakia (SK). (Source: Eurostat)

The euro area had approximately 19.1 million unemployed people in December 2013, 130,000 more than in December 2012, but 129,000 fewer than in November 2013.

ECB under pressure to reduce interest rates – CNN Money quoted Howard Archer, IHS Insight’s chief European economist, who said “[January’s inflation figure] puts significant pressure on the ECB to take further stimulative action at its February policy meeting next Thursday.” He added that cheaper energy was largely to blame for the fall in inflation, as well as a stronger euro which has been pulling down the prices of imports.