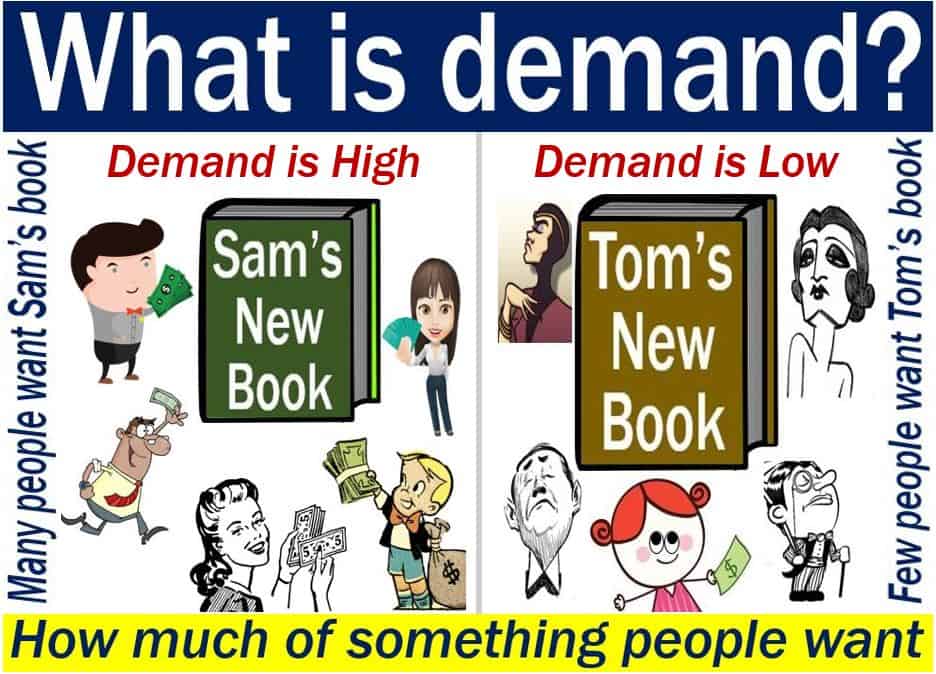

Demand in economics refers to the measure of desire to own and purchase a product or service. When the price of a product rises, demand for it goes down. In other words, demand is how much consumers are willing or able to buy something. It refers to a buyer’s willingness to pay a price for something.

It is how much an individual consumer or group of consumers want to buy something at a given price. When the price for a particular product goes down, more people will want it. In fact, the drop in price makes people want more of it.

However, if its price increases, the opposite occurs. We call this demand response to a price change the demand curve.

Several factors, apart from price, determine the level of demand. For example, the availability of similar products made by competitors can influence how much people want something. If something I want is not available, I might buy a substitute good.

To request/ask forcefully

If you ask for something strongly and show that you expect to get it, we say you ‘demand’ it. For example, when you say ‘I demanded a pay rise,’ it means you confidently asked for more money in your job, and you expected to get it.

The Cambridge Dictionary has the following definition of ‘demand’:

“1. (Verb) To ask for something forcefully, in a way that shows that you do not expect to be refused. 2. (Noun) A need for goods or services that customers want to buy or use.”

This article focuses on the term ‘demand’ when it is used in economics.

The opposite of ‘supply’

The term ‘supply’ has the opposite meaning. The higher the supply, the lower the proportional demand, and thus the price.

In some cases, demand is said to be infinite. No matter how much supply grows for some things, people’s desire for them appears to grow too.

For example, as suppliers provide more bandwidth, consumers seem to want more and more of it.

People’s desire for health services and products appears to be infinite. Medical breakthroughs nearly always result in greater demand for medical services.

Factors that determine demand

Several factors and circumstances can affect consumers’ willingness or ability to buy something. The most common ones are:

-

Price

Generally, as price rises consumers buy less of a product. Conversely, as the price declines people want more of it. This phenomenon is clearly visible in a consumer demand curve.

-

Prices of complements

The price of complements influences how much consumers want something. A complement is something that we used with the primary product.

For example, when we buy a hamburger we also consume ketchup – ketchup is the complement. Other examples include cars and gasoline (UK: petrol), or bread and butter.

Perfect complements, however, behave as a single item. For example, a left shoe is a perfect complement for a right shoe, and vice-versa.

If the product’s price increases, sales of its complement decline. Therefore, if people buy fewer cars, sales of gasoline will suffer.

-

Quality

Quality influences people’s purchasing decisions. It can even put people off – when this happens, we call it quality creep.

Quality creep occurs when the manufacturer keeps improving a product and raising its price. Eventually, consumers go elsewhere because they are not willing to pay a premium for all its ‘bells and whistles.’

-

Price of substitutes

Substitute goods are identical products made by competitors. For example, in the toothpaste market, Crest and Colgate are substitutes. Other examples include McDonald’s and Burger King hamburgers, Pepsi-Cola and Coca-Cola sodas.

In other words, we can use the substitute in place of the primary product. If the substitute’s price goes down, the demand for the primary product declines.

For example, if Burger King slashes the price of its hamburgers, sales of McDonald’s hamburgers decline. However, if Burger King raises prices, people will buy more McDonald’s hamburgers.

-

Personal Disposable Income

Personal disposable income refers to how much spare cash we have. The more disposable income we have, the more demand is likely to grow.

Personal disposable income is income after tax or ‘net income.’ We can also say ‘disposable personal income.’

Some people define personal disposable income as spare money after paying for everything. In other words, after paying tax, loan/mortgage monthly repayments, food, clothes, vacations, utilities, etc.

-

Preferences or Tastes

The stronger the desire to obtain or own a particular good, the more likely we are to buy it. Desire and demand are not the same.

With desire, we base our willingness to buy something on its intrinsic qualities. However, we base demand on our ability and willingness to act on that desire.

Many things can change our tastes or preferences. For example, if a famous and popular celebrity endorses a new product, some of us will want more of it.

Additionally, advertising and marketing strategies significantly impact demand by shaping consumer preferences, creating perceived needs, and often encouraging the consumption of certain products over others.

Moreover, the rise of digital platforms and e-commerce has revolutionized consumer behavior, making it easier for consumers to compare prices and products, thus often intensifying demand for goods and services in a more connected, global marketplace.

However, demand is likely to fall if a new health study warns that something is bad for you.

The weather can alter what we want to buy. For example, umbrella sales spike on a rainy day, while ice-cream sales rise during a heatwave.

-

Future Expectations

If you expect the price of something to go up soon, you are more likely to buy it now. However, if you expect its price to remain constant, you are less likely to purchase it now.

You are more likely to buy something now if you expect your income to rise soon. Availability or expected availability impact how much we want something, as well as its price.

-

Population

If a city’s population grows, so will the price of property in that city. Property prices within commuting distances will also rise.

-

A Basic Commodity

Demand for a basic commodity usually increases over time. A basic commodity is a staple farm produce that is produced in large quantities, such as sugar corn.

Demand and ‘the income effect’

Economists often talk of the income effect. The income effect refers to how a change in disposable income can change demand for a product.

Luxury goods, for example, are popular when people have more spare cash. However, the opposite occurs with inferior goods, such as bus-passes.

When consumers have more disposable income, they use cheaper forms of transport less and travel more by car.

When the desire to purchase something is still dormant we call it latent demand. This may occur if consumers cannot afford the item, the item is not available, or consumers think it is not available.

When we buy things that are bad for us, we call it unwholesome demand. We all know that smoking is bad for us. There are government warnings as well as documentaries telling us how dangerous cigarettes are. In spite of all these warnings, people still buy cigarettes.

Derivatives of ‘demand’

From the root word ‘demand’ we get many derivatives. Let’s have a look at them:

-

Demander (noun)

A person who demands. As in:

“The manager was a tough demander, always insisting on the highest standards from her team.”

-

Demanded (past tense and past participle of demand)

Indicating that something was requested or required firmly. As in:

“He demanded a refund for the faulty product he had purchased.”

-

Demanding (adjective)

Describing something or someone requiring much effort or attention. As in:

“Being a nurse is a demanding job, requiring both physical stamina and emotional strength.”

-

Undemanding (adjective)

Describing something that does not require much effort or attention. As in:

“She preferred undemanding tasks during the end of her shift to wind down.”

-

Demandable (adjective)

Capable of being demanded. As in:

“The overdue payment was demandable, so the creditor sent a formal request for immediate payment.”

-

Overdemanding (adjective)

Excessively demanding; requiring too much effort or attention. As in:

“His overdemanding nature led to high turnover in his department, as employees felt overwhelmed by his expectations.”

‘High turnover,’ in this context, refers to staff members leaving for a negative reason. If a department has a high turnover, it means that employees don’t stay long; they soon resign.

Video – What is demand?

This video, from our sister channel on YouTube – Marketing Business Network, explains what ‘Demand’ is using simple and easy-to-understand language and examples.