We live in a drying world, and more than four billion people face a water shortage, that’s more than half our planet’s population, say two scientists from the University of Twente in the Netherlands. They say that people need to adapt and change, because with climate change, the situation is not going to get any better.

Quite simply, as far as more than half Earth’s population is concerned, we are using more water than is sustainably available – water demand is greater than supply for at least one month of each year. The number of people in this water scarcity club is likely to increase.

In some parts of the world, disputes and even battles over water have not been uncommon. The management of the Klamath River in the western United States has for generations seen communities clash. While potato farmers and livestock ranchers needed water for irrigation, native Americans, conservationists, anglers and hunters insisted that the river should be left alone so that wildlife – fish and waterfowl – could thrive.

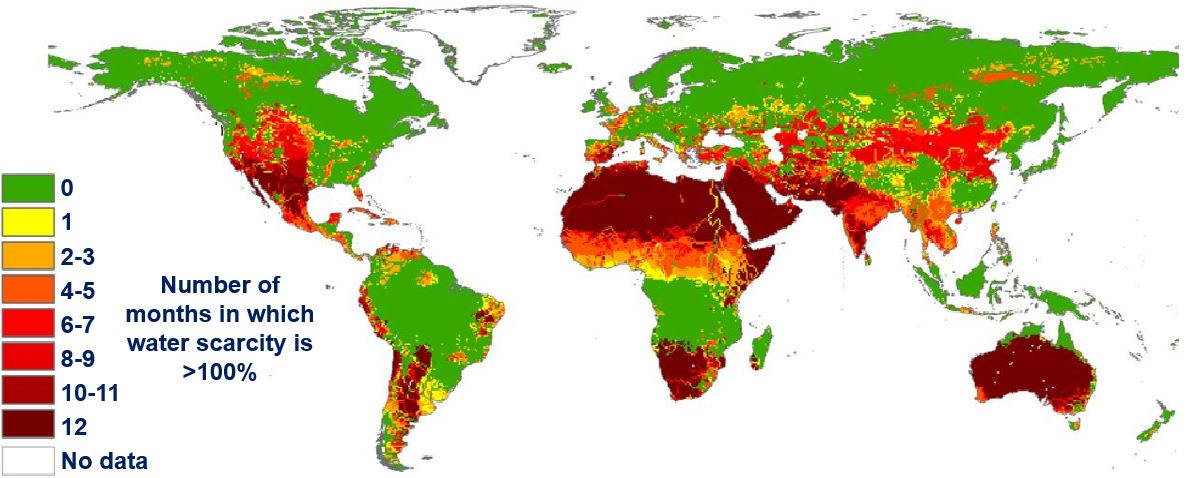

This map was for the period 1996-2005. The areas in dark red/brown will grow while the green regions will shrink as this century progresses. The authors say people must learn to adapt and change. (Image: Science Advances)

This map was for the period 1996-2005. The areas in dark red/brown will grow while the green regions will shrink as this century progresses. The authors say people must learn to adapt and change. (Image: Science Advances)

Even today, when summer arrives and the rains stop and water levels plummet, people’s blood still boils in that part of America.

However, no geographer worth his or her salt would ever have told you that the basin was experiencing a ‘water scarcity’, because it was a problem that only emerged during the dry summer.

What is a water scarcity?

Any scarcity, be it water, medicine, plumbers, or skills, exists when supply exceeds demand – when the usage or consumption of something is unsustainable.

As far as the Klamath Basin is concerned, the water scarcity exists only during the summer, but most studies in the past have been done on an annual basis. Water is only in short supply there during the months of July, August and September; for the rest of the year there has been no problem.

In this new study, carried out by Arjen Hoekstra and Mesfin Mekonnen, and written about in the academic journal Science Advances (citation below), water scarcity is shown on a monthly timescale.

In the Klamath Basin, their maps show that more water is taken out than the region can sustainably support for at least one month in every year. Across the world, more than four billion people live in similar areas.

The Klamath basin in western USA. It is amazing how reasonable people can be if you give them all the facts. Groups of people who for generations hated each other have sat down and agreed to consume less water. Now we need to get every community in water-scarce areas globally to sit down at the negotiating table. (Image: Wikipedia)

The Klamath basin in western USA. It is amazing how reasonable people can be if you give them all the facts. Groups of people who for generations hated each other have sat down and agreed to consume less water. Now we need to get every community in water-scarce areas globally to sit down at the negotiating table. (Image: Wikipedia)

A slightly smaller number of people (but nearly 4 billion) live in areas where two times as much water is withdrawn as is sustainably available for one month or more of each year.

Global assessments, which looked at water demand and supply on annual bases, calculated that from 1.7 to 3.1 billion people withdrew more water than was sustainably available.

Calculating water availability on a monthly basis

Mekonnen, who works at the Faculty of Engineering Technology at Twente’s Department of Water Engineering & Management, and Koeksra, chair of the Department of Water Engineering & Management, estimated monthly withdrawal of water for each location by combining data of crop types, water evaporation, and population density, and then compared the results with how much water was available in lakes and rivers.

They assumed that four-fifths of the water would have to remain in the lakes and rivers to support ecosystems. If locals started using this reserve, the scientists would judge that that location was ‘water scarce’ for that month.

Their maps include several ‘dry’ places, apart from the Middle East and Australia – areas we all know about. They include parts of Mexico and Africa, Turkey, southern Europe, northern China and Central Asia, regions of the world were periods of water shortage may cause hardship among local populations.

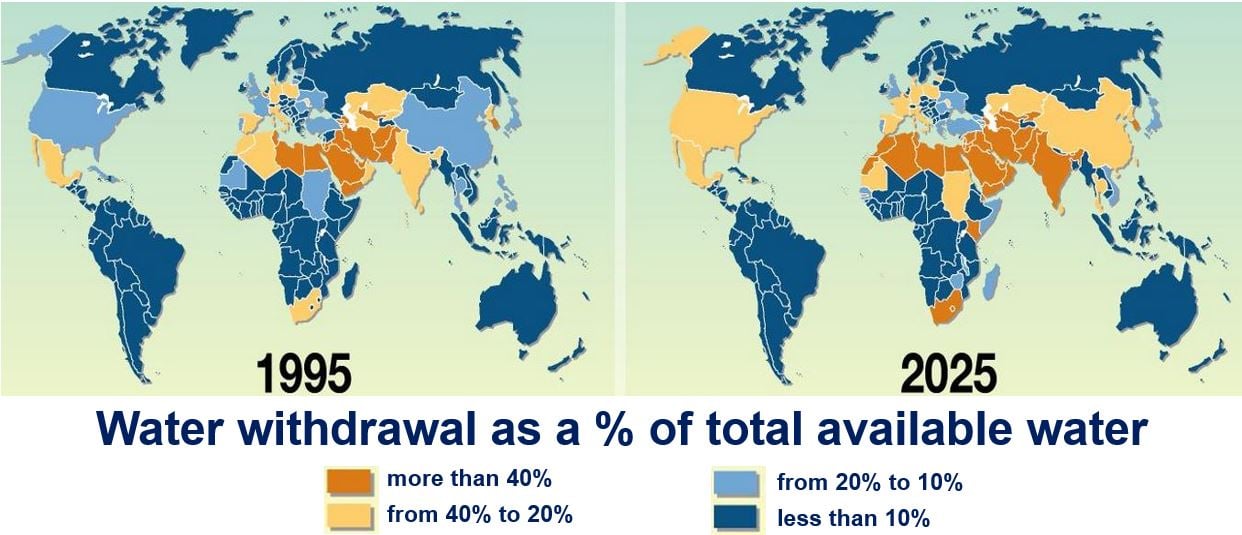

According to this United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) forecast, the USA, France, and China suddenly appear on the map in 2025 as countries with significant water scarcity problems in 2025. If nothing is done, what will the 2050 map look like? (Image: unep.org)

According to this United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) forecast, the USA, France, and China suddenly appear on the map in 2025 as countries with significant water scarcity problems in 2025. If nothing is done, what will the 2050 map look like? (Image: unep.org)

Effects of water scarcity not only local

Hoekstra explains that water scarcity does not only affect local people. For example, Europe imports food and other products from China, which relies on a healthy supply of water to deliver those goods.

Emma Marris, writing in Nature News, quotes Jacob Schewe, a water specialist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research in Germany, who says that Hoekstra’s and Mekonnen’s map can be seen as a guide for environmental and developmental institutions that work with water.

Schewe has created maps of water scarcity that make predictions regarding how the pattern will be affected by climate change. According to his maps, China is among several regions that will become drier as this century progresses.

Mekonnen and Hoekstra’s analysis begins to define how much water each area can safely withdraw on a monthly basis. Policymakers can use this data to determine consumption limits and prices.

Sometimes we need to feel it to understand it. The University of Texas at Austin wrote: “The 2011 drought in Texas, the state’s worst single-year drought in history … ended up being the mother of all teaching moments. The lessons learned are not pleasant, but addressing them will give the state a fighting chance when the next major drought comes around.” (Image: utexas.edu)

Sometimes we need to feel it to understand it. The University of Texas at Austin wrote: “The 2011 drought in Texas, the state’s worst single-year drought in history … ended up being the mother of all teaching moments. The lessons learned are not pleasant, but addressing them will give the state a fighting chance when the next major drought comes around.” (Image: utexas.edu)

What happens when we dip into water reserves?

Schewe said:

“You can still get water from somewhere, but it might mean you get it from a really important ecosystem that dries out and dies while you are swimming in your swimming pool.”

Klamath Basin coordinator for the Fish and Wildlife Service in Yreka, California, Matt Baun, says that the recent years’ over-consumption of water from the Klamath River has resulted in the deaths of many juvenile salmon. It has also reduced the amount of open water and food for migratory birds at wildlife refuges – the incidences of botulism and avian cholera because of crowding have increased considerably.

Hoekstra urges people who live in places that are water scarce – according to his map – to learn how to adapt and change.

In the Klamath Basin, former enemies are now agreeing to consume less water. Jason Atkinson, an American politician in the US state of Oregon – also a filmmaker who created a documentary ‘A River Between us‘ – said “If you heal people, they would heal the river.”

In an Abstract in Science Advances, Hoekstra and Mekonnen wrote:

“Putting caps to water consumption by river basin, increasing water-use efficiencies, and better sharing of the limited freshwater resources will be key in reducing the threat posed by water scarcity on biodiversity and human welfare.”

Citation: “Four billion people facing severe water scarcity,” Mesfin M. Mekonnen and Arjen Y. Hoekstra. Science Advances, Vol. 2, no. 2, e1500323. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500323.

Video – Fresh water scarcity

We cannot live without fresh water – and there’s nowhere near enough of it in the world right now. Why is that, and what could we do? Christiana Z. Peppard, Assistant Professor of Theology, Science, and Ethics at Fordham University in New York, lays out the big questions of our global water problem. Unfortunately, it is not as simple as taking shorter showers.