Giant icebergs slow down global warming as they melt in the ocean, say researchers from Sheffield University’s Department of Geography. Melting water from mega icebergs releases enormous quantities of iron and other nutrients into the sea.

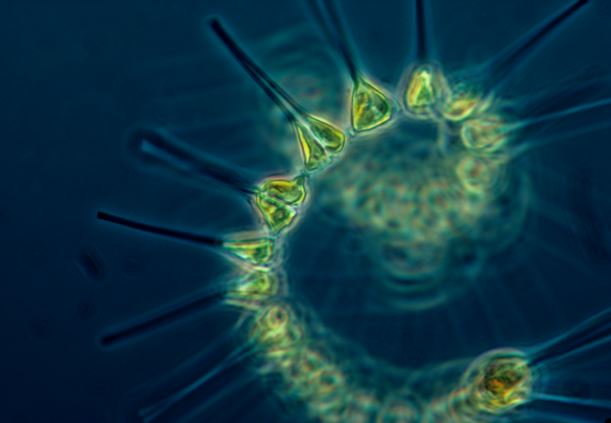

This release helps maintain unexpectedly high levels of phytoplankton growth. Phytoplankton are microscopic plants that live in the ocean. They are at the base of the oceanic food chain. Many small fish and whales eat them. They also absorb carbon dioxide during photosynthesis.

This activity of phytoplankton – known as carbon sequestration – assists in the long-term storage of CO2 (carbon dioxide) in the atmosphere, thus helping slow down global warming.

Giant icebergs are responsible for storing up to 20% of carbon in the Southern Ocean, the Sheffield study found. (Image: sheffield.ac.uk)

Giant icebergs are responsible for storing up to 20% of carbon in the Southern Ocean, the Sheffield study found. (Image: sheffield.ac.uk)

Melting icebergs indirectly boost carbon sequestration

Carbon sequestration is a process (natural or artificial) by which CO2 is removed from the air and held in liquid or solid form.

Details of this latest study were published in an article in the scientific journal Nature Geoscience.

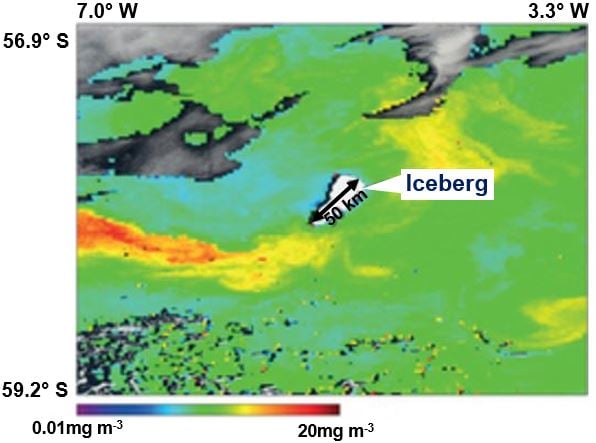

During the study, which the authors claim is the first of its kind on this scale, team leader Grant Bigg, Professor in Earth Systems Science at Sheffield University’s Department of Geography, and colleagues analysed 175 satellite images of ocean colour. The colour of the ocean is an indicator of phytoplankton productivity on the surface of the sea.

They focused on the water around a range of icebergs in the Southern Ocean that were at least 18 kilometres (11.2 miles) long – approximately the length of Manhattan island.

The Southern Ocean, also called the Antarctic Ocean or the Austral Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean.

Greater phytoplankton productivity around giant icebergs

The satellite images captured from 2003 to 2013 showed that greater phytoplankton productivity extended hundreds of kilometres from the giant icebergs, and persisted for at least one month after the iceberg had passed. This has a direct impact on carbon storage in the ocean.

Chlorophyll-a concentration on 12 January 2013, from the MODIS Aqua satellite. Giant iceberg C16 is visible in the centre of the image, with enhanced levels spreading southwest and northeast from the iceberg. Greyscale areas represent cloud cover. (Image: nature.com)

Chlorophyll-a concentration on 12 January 2013, from the MODIS Aqua satellite. Giant iceberg C16 is visible in the centre of the image, with enhanced levels spreading southwest and northeast from the iceberg. Greyscale areas represent cloud cover. (Image: nature.com)

Prof. Bigg said:

“This new analysis reveals that giant icebergs may play a major role in the Southern Ocean carbon cycle. We detected substantially enhanced chlorophyll levels, typically over a radius of at least four-10 times the iceberg’s length.”

“The evidence suggests that assuming carbon export increases by a factor of five-10 over the area of influence and up to a fifth of the Southern Ocean’s downward carbon flux originates with giant iceberg fertilisation.”

“If giant iceberg calving increases this century as expected, this negative feedback on the carbon cycle may become more important than we previously thought.”

Phytoplankton are the foundation of the oceanic food chain. They are too small to be individually seen with the naked eye. The water from melting giant icebergs helps phytoplankton growth, which reduces CO2 levels in the atmosphere. (Image: Wikipedia)

Phytoplankton are the foundation of the oceanic food chain. They are too small to be individually seen with the naked eye. The water from melting giant icebergs helps phytoplankton growth, which reduces CO2 levels in the atmosphere. (Image: Wikipedia)

This study challenges previous findings

The Southern Ocean plays a major role in the global carbon cycle. Approximately 10% of all the carbon sequestration in our oceans – through a combination of biologically and chemically driven processes, including phytoplankton growth – occurs in the Southern Ocean.

The findings in this study challenge previous research which had suggested that ocean fertilization from icebergs made relatively minor contributions to phytoplankton uptake of carbon dioxide.

This research, however, clearly shows that melting water from giant icebergs is responsible for up to 20% of the carbon sequestered to the depths of the Southern Ocean.

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors concluded:

“Assuming that carbon export increases by a factor of 5–10 over the area of influence, we estimate that up to a fifth of the Southern Ocean’s downward carbon flux originates with giant iceberg fertilization. We suggest that, if giant iceberg calving increases this century as expected4, this negative feedback on the carbon cycle may become more important.”

Citation: “Enhanced Southern Ocean marine productivity due to fertilization by giant icebergs,” Luis P. A. M. Duprat, Grant R. Bigg & David J. Wilton. Nature Geoscience. 11 January, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo2633.