Migratory birds are at serious risk of extinction due to the loss of **habitat and lack of protection along their flight paths, a team of scientists revealed after carrying out a comprehensive study. Over ninety percent of migratory birds across the world are inadequately protected, say the researchers, led by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions (CEED), the world’s leading research centre for solving environmental management problems.

** An animal’s habitat is where it eats, sleeps, finds a mate, and finds shelter.

According to the study’s findings, which have been published in the journal Science, there are massive gaps in the conservation of migratory birds, particularly across India, China, and parts of South America and Africa.

This means that most species of migratory birds are flying over well-protected areas in one country, and then poorly-protected regions in another.

The Alaska Science Center tracked one Bar-Tailed Godwit (orange track) for 29,280 km. Another (blue track) was tracked for 21,210 km. (Image: alaska.usgs.gov. Credit: Battley et al. 2011, J. of Avian Biol. 43: 21-32)

The Alaska Science Center tracked one Bar-Tailed Godwit (orange track) for 29,280 km. Another (blue track) was tracked for 21,210 km. (Image: alaska.usgs.gov. Credit: Battley et al. 2011, J. of Avian Biol. 43: 21-32)

Migratory bird populations declining significantly

Lead author Dr. Claire Runge of CEED and the University of Queensland, said:

“More than half of migratory bird species travelling the world’s main flyways have suffered serious population declines in the past 30 years.”

“This is due mainly to unequal and ineffective protection across their migratory range and the places they stop to refuel along their routes. A typical migratory bird relies on many different geographic locations throughout its annual cycle for food, rest and breeding.”

“So even if we protect most of their breeding grounds, it’s still not enough – threats somewhere else can affect the entire population,” she says. “The chain can be broken at any link.”

Some birds travel incredible distances

These birds undertake extraordinary journeys, Dr. Runge explains, they navigate across sea and land to find refuge as the seasons change.

The Bar-Tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica), a large wader which breeds on Arctic coasts and tundra, spends its winters – 10,000 kilometres away – on coasts in temperate and tropical regions of the Old World and of New Zealand and Australia.

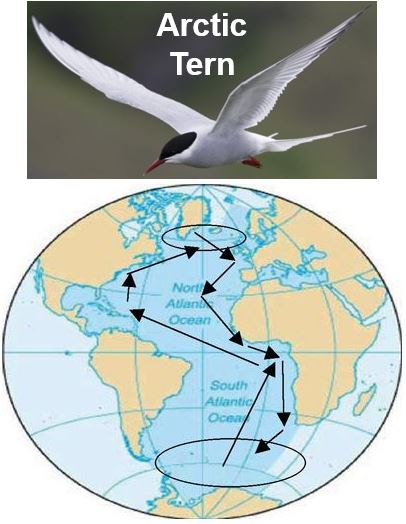

The Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea), a seabird of the tern family that sees two summers each year, flies the equivalent of the Moon and back three times during the course of its life.

The National Audubon Society says the Arctic Tern is famous as a long-distance champion. Some may migrate farther than any other birds, going from the high Arctic to the Antarctic. (Image: adapted from www.audubon.org)

The National Audubon Society says the Arctic Tern is famous as a long-distance champion. Some may migrate farther than any other birds, going from the high Arctic to the Antarctic. (Image: adapted from www.audubon.org)

Other examples include the Sooty Shearwater (Puffinus griseus), known as tītī or muttonbird in New Zealand, which flies 64,000 kilometres, and the tiny Blackpoll Warbler (Setophaga striata), which flies for three days non-stop over the ocean from eastern Canada to South America.

Lack of protection in many areas

Of the 1,451 migratory bird species studied in this latest research, 1,324 were found to have inadequate protection for at least one part of their migratory route.

Eighteen species have no protection at all in their breeding areas, while two species have no protection whatsoever along their whole flightpath.

For the migratory bird species that are listed as threatened – according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List by BirdLife International – fewer than 3% have sufficient protected areas.

Co-author Dr. Stuart Butchart, Head of Science at BirdLife International, said:

“For example, the red-spectacled amazon – a migratory parrot of Brazil – is threatened by habitat loss. And yet less than four per cent of its range is protected, and almost none of its seasonal breeding areas in southern Brazil are covered.”

The researchers also assessed more than 8,200 areas that have been identified as internationally important locations for migratory birds.

Only twenty-two percent of those areas were found to be completely protected. Forty-one percent partially overlap with protected areas.

Dr. Butchart said:

“Establishing new reserves to protect the unprotected sites – and more effectively managing all protected areas for migratory species – is critical to ensure the survival of these iconic species.”

The Blackpoll Warbler breeds in Northern Canada (yellow) and winters in South America (blue). (Image: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackpoll_warbler)

The Blackpoll Warbler breeds in Northern Canada (yellow) and winters in South America (blue). (Image: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackpoll_warbler)

International coordination crucial

Associate Professor Richard Fuller of CEED, who was also a co-author, said the results highlight the urgent need to coordinate all the protected areas along the birds’ full migration routes.

Prof. Fuller explained:

“For instance, Germany has protected areas for over 98 per cent of the migratory species that pass its borders, but fewer than 13 per cent of its species are adequately protected across their global range.”

“It isn’t just a case of wealthy nations losing their migratory birds to a lack of protection in poorer nations. Many Central American countries, for example, meet the targets for more than 75 per cent of their migratory species, but these same species have less protected area coverage in Canada and USA.”

While protected areas are generally designated by each nation, collaborative cross-border partnerships and inter-governmental coordination, as well as action are vital to safeguard the world’s migratory birds.

Prof. Fuller warned:

“It won’t matter what we do in Australia or in Europe if these birds are losing their habitat somewhere else – they will still perish. We need to work together far more effectively round the world if we want our migratory birds to survive into the future.”

Citation: “Protected areas and global conservation of migratory birds,” Claire A. Runge, James E. M. Watson, Stuart H. M. Butchart, Jeffrey O. Hanson, Hugh P. Possingham, and Richard A. Fuller. Science. 4 December 2015: 350 (6265), 1255-1258. [DOI:10.1126/science.aac9180].

Video – Migratory birds in danger

Discover more from Market Business News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.