In 1959, the Natural History Museum’s principal scientific officer, Dr. Denys Tucker (1921-2009), said he saw Nessie the Loch Ness Monster, a claim which displeased his bosses and eventually cost him his job.

Dr. Tucker, an eminent zoologist and fish expert, and a world authority on eels, was a well-respected scientist when he joined the Museum in 1949 as a scientific officer in the zoology department, after serving as a pilot in WWII.

At the age of 28, he was by far the youngest scientist at the Museum. He rapidly climbed the career ladder until becoming a senior scientist in 1951 and then principal scientific officer in 1957.

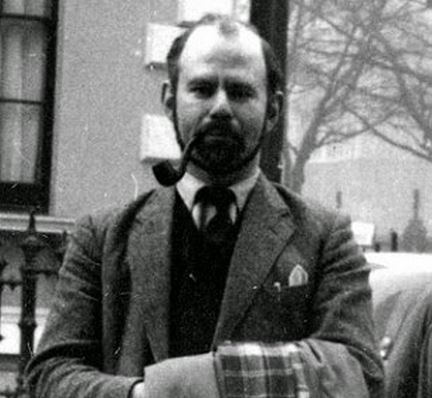

Denys Tucker (1921-2009). (Image: lochnessmystery.blogspot.co.uk)

According to papers released under the Freedom of Information Act and reported by the Independent, senior academics and his bosses once said “Most people who know him would agree that in intelligence he is to be classed with a few of our most brilliant colleagues.”

Nessie sighting ruined his career

However, in 1959 his career dramatically changed paths after he claimed he had seen an ‘unnamed animal’ breach the surface of Loch Ness.

In a letter to the New Scientist, Dr. Tucker said the animal he saw must have been an Elasmosaurus, a genus of plesiosaur with an extremely long neck that existed in the Late Cretaceous period (Campanian stage), 80.5 million years ago.

Dr. Tucker wrote:

“I am quite satisfied that we have in Loch Ness one of the most exciting and important findings of British zoology today.”

Members of the general public were fascinated by his claim, and many visited Loch Ness in an attempt to see what he had claimed to witness. His sighting triggered three decades of academic research into the Scottish lake.

Dr. Tucker believed the creature he saw could only be an Elasmosaurus. (Image: paleoaerie.org)

Unsuitable topic for top scientist

However, Museum bosses were displeased. Documents show that Museum chiefs asked Dr. Tucker whether he considered his new interest in Nessie to be a suitable topic for an eminent scientist working in one of the world’s most prestigious museums.

Stories and rumours started circulating about his previous work and his ‘dubious’ disciplinary record. There was even speculation about the sex lives of colleagues and claims he had once waved a pistol at a superior.

Things came to a head in 1960 when Dr. Morrison-Scott, who became the Museum’s new director, decided to fire Dr. Tucker.

Dr. Tucker reacted to his dismissal by launching a legal campaign to be reinstated – Museum trustees were sued in person.

In those days, suing trustees was not like taking a bunch of academics to court today. In 1960, Dr. Tucker had to launch cases against the Speaker of the House of Commons, Harry Hylton-Foster, and Archbishop Lord Fisher, who was head of the Church of England. A marquess was also taken to court as were two viscounts.

There was serious concern among those in power that if Dr. Tucker won, they would never again be able to fire a civil servant.

Dr. Tucker’s case made it all the way to the Court of Appeal, despite concerted efforts by the government to keep top figures out of the witness box. The Court of Appeal tossed out the case.

Dr. Tucker became convinced for life that the corridors of power were involved in an attempt to cover up claims of Nessie sightings. He never held an academic post again.

Dr. Tucker settled in Wimbledon following the collapse of his court case, and then moved to France, where he died in 2009.