Since the 1800s, there has been an explosion of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) populations in the lakes of Europe and North America, which threatens to poison our drinking water and maybe raise the risk of developing Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, British, Canadian, French, Italian, Spanish and Malaysian researchers reported this week.

Scientists from McGill University in Canada and the University of Nottingham in England, who published their findings in the academic journal Ecology Letters, say the algae surge is a result of pollution.

The team gathered and examined data on over 100 lakes in alpine and lowland areas of Europe and North America and were surprised to find an alarming increase in the amount of cyanobacteria in our waters over the past 200 years.

Cyanobacteria populations have increased more in lakes near farmland. (Image: McGill University)

The researchers say theirs is the first study to show that the algae’s available nutrient sources phosphorus and nitrogen – commonly resulting from sewage discharge and fertilizers – are probably the main factors driving the increase in concentrations of cyanobacteria in so many lakes across such a huge geographical area.

The scientists also discovered that global warming can aggravate the problem. Water management challenges are likely to grow as the planet gets warmer in future, they commented.

Zofia Taranu, who led the study as a PhD candidate in McGill’s Department of Biology, said:

“We found that cyanobacterial populations have expanded really strongly in many lakes since the advent of industrial fertilizers and rapid urban growth.”

“While we already knew that cyanobacteria prefer warm and nutrient-rich conditions, our study is also the first to show that the effect of nutrients, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, overwhelm those of global warming.”

Water contamination

The majority of municipal water treatment plants do not routinely check their water supply for cyanobacterial toxins. The only ones that do are those with a known history of algal blooms.

The algae, when detected, can be removed by adding a chemical that binds them together, then they can be separated out. While this is an effective way of removing the cells, they may have already broken down and released toxins into the water.

In Australia and the United Kingdom, the environmental costs associated with this alga are estimated to be more than $100 million annually.

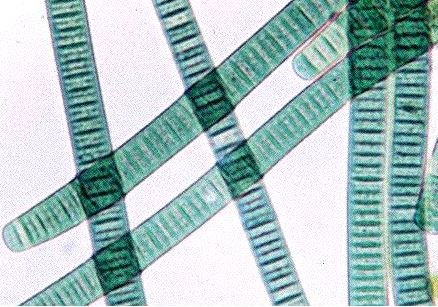

Cyanobacteria obtain their energy through photosynthesis (Image: University of California Museum of Paleontology)

Nottingham researchers Heather Moorhouse, Mark Stevenson, and Dr Suzanne McGowan took samples cores of sediment from lakes in the major UK lake districts including the upland lakes in Northern Ireland, Scottish lochs, the West Midland Meres, and the English Lake District, and analysed them for pigments left behind by the blue-green algae.

These pigments, which remain stable over thousands of years, act as biomarkers and provide scientists with data on past levels of algae found in water over the course of decades.

Rapid increase in lakes near farms

The analysis showed that 58% of lakes over the past 200 years had seen considerable increases in blue-green algae pigment concentrations, but only 3% showed significant increases in algae populations.

Lowland lakes next to agricultural land were found to be especially susceptible to increases in cyanobacteria populations. Most British lakes are near agricultural catchments.

The authors also reported that since 1945 the incidence of blue-green algae has increased faster than the growth of other kinds of water-borne algae.

The greatest increases were observed in more temperate lowlands – 70% in Europe and 61% in North America – which were nearer to farms than in alpine areas (36%).

Analysis of blue-green algae population trends across 10 countries in three continents showed that growth was mainly driven by a change in the amount of nutrients – nitrogen and phosphorus – found within the lakes.

The authors say their findings underlie the importance of further study into how to control the inputs of phosphorus- and nitrogen-rich pollutants, and ways to monitor the resulting toxins in our drinking water.

Cyanobacteria neurotoxin BMAA linked to neurodegenerative disease risk

Over the past few years, some scientific studies have started linking exposure to the cyanobacteria neurotoxin BMAA with a higher risk of developing several types of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and ALS.

A study published in the academic journal Acta Neurologica Scandinavica concluded:

“The occurrence of BMAA in North American ALS and AD patients suggests the possibility of a gene/environment interaction, with BMAA triggering neurodegeneration in vulnerable individuals.”

Citation: “Acceleration of cyanobacterial dominance in north temperate-subarctic lakes during the Anthropocene,” Zofia E. Taranu, Irene Gregory-Eaves, Peter R. Leavitt, Lynda Bunting, Teresa Buchaca, Jordi Catalan, Isabelle Domaizon, Piero Guilizzoni, Andrea Lami, Suzanne McGowan, Heather Moorhouse, Giuseppe Morabito, Frances R. Pick, Mark A. Stevenson, Patrick L. Thompson and Rolf D. Vinebrooke. Ecology Letters. Published online Feb 26, 2015. DOI: 10.1111/ele.12420.