Sir Paul Nurse, who was awarded the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, warns that Brexit (Britain Exit from the European Union) would be bad for the country, and attacks the short-term political opportunism that some politicians are currently pursuing. Another group of scientists (details below) disagrees and insists UK science and British scientists would be better off leaving the economic bloc.

If the United Kingdom votes to leave the European Union (EU) in an in-or-out referendum on 23rd June, 2016, the country’s research will suffer, says Sir Paul, who is the current director of The Francis Crick Institute.

Sir Paul Nurse, a former President of the Royal Society, says that after a Brexit, British scientists would find it much more difficult to get research and development funding – the move would sell ‘future generations short’, he added.

Sir Paul Nurse says that Britain today is among the few world leaders in scientific research and development. If we left the European Union, we could slip out of the world stage. If we turn our back on the EU, it may turn its back on us, he warns.

Sir Paul Nurse says that Britain today is among the few world leaders in scientific research and development. If we left the European Union, we could slip out of the world stage. If we turn our back on the EU, it may turn its back on us, he warns.

Politicians and other individuals who are campaigning for Britain to leave the EU are jeopardizing the long-term future of the country, including its world-leading scientific research ‘for short-term political advantage’, he warned.

Sir Paul Nurse said:

“We need a vision for our future that is ambitious and not to run away and bury our heads in the sand, and we can best do this by staying in the EU. We should not be side-tracked by short-term political opportunism.”

The Nobel laureate was speaking at a news briefing about the consequences of a withdrawal from the economic bloc for British scientist. He was flanked by other eminent scientists who also believe that their country’s best future lies within the EU.

Prof. Nurse said:

“Being in the EU gives us access to ideas, people and to investment in science. That, combined with mobility (of EU scientists), gives us increased collaboration, increased transfer of people, ideas and science – all of which history has shown us drives science.”

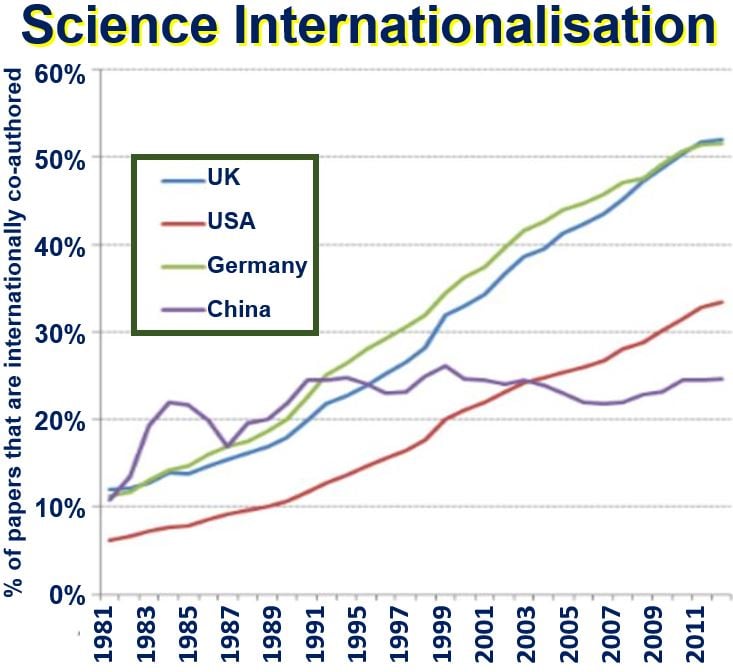

Dr. Mike Galsworthy and Dr. Rob Davidson wrote in a London School of Economics blog that since 1980, global research has become rapidly more international. Over 50% of all UK scientific papers today are of international collaborations, compared to 15% in 1981. Would leaving the EU change this trend? (Image: blogs.lse.ac.uk)

Dr. Mike Galsworthy and Dr. Rob Davidson wrote in a London School of Economics blog that since 1980, global research has become rapidly more international. Over 50% of all UK scientific papers today are of international collaborations, compared to 15% in 1981. Would leaving the EU change this trend? (Image: blogs.lse.ac.uk)

Only as part of the EU does Britain expect to have any influence in directing research on the world stage, which it currently dominates alongside other ‘powerhouses’ of science, including the United States and China.

Other group of scientists backs Brexit

A group of scientists that supports Brexit – Scientists for Britain – says that it is a myth to believe that the country’s scientific community is somehow less robust than it appears, and leaving the European union would have an unduly adverse impact on UK science.

The group says the UK has always been a major player in the world stage regarding science, and quotes a recent UNESCO Science Report that showed that for a country with just 0.9% of the world’s population, Britain has 3.3% of its scientific researchers, who in turn produce 6.9% of global scientific output.

Scientists for Britain wrote on its website:

“Indeed, a recent UK Government funding document found that the UK produced around 15.1% of the world’s most highly-cited (or regarded) scientific papers. From these figures, there is no doubt that our industrious and talented scientists punch way above their weight when it comes to global science – hardly a position of weakness.”

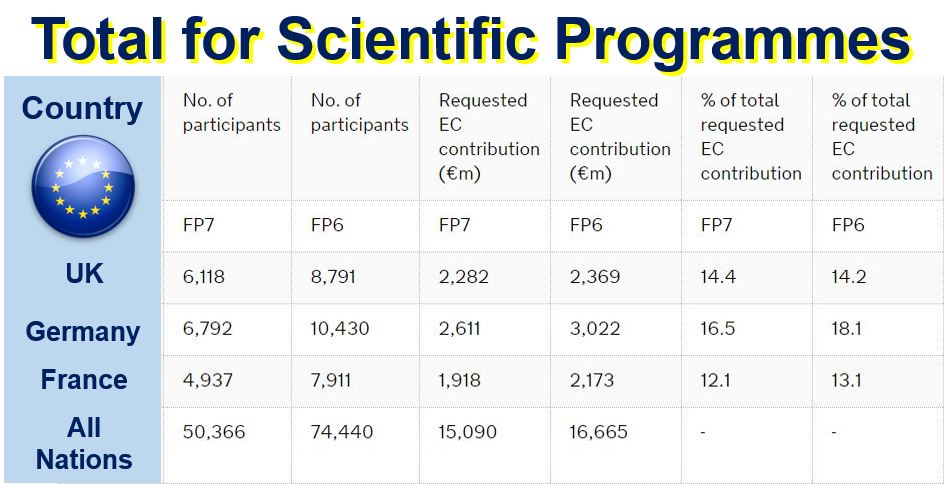

EU funding for British scientific programmes is tiny, pro-Brexit group ‘Scientists for Britain’ says, especially compared to how much money the UK Government contributes. (Image: www.gov.uk)

EU funding for British scientific programmes is tiny, pro-Brexit group ‘Scientists for Britain’ says, especially compared to how much money the UK Government contributes. (Image: www.gov.uk)

The group quantifies the potential impact of Britain leaving the EU by looking at the current impact of EU funded science networks on British science.

For the financial year 2015/16, £5.8 billion was invested overall in UK scientific research and development by the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS), according to a UK Allocation of Science and Research Funding 2015/16 document.

Contrastingly, the European Research Council (ERC), the organization that awards funding for projects done through EU science networks, has a budget of just £1.3 billion for 2016 – to fund all the twenty-eight member states and the 13 non-EU nations that participate in its programmes.

The United Kingdom received about 14.4% of European Research Council funds from the most recent funding programme – FP7 – which comes to a total of £190 million of EU science funding for the whole of 2016.

Regarding EU funding for UK science, Scientists for Britain commented:

This suggests that the potential EU contribution to UK Science from the ERC’s Horizon2020 programme in 2016 is around 3.3% of that derived from the UK government, which adds weight to our argument that leaving the political structures of the EU would have no more than a 10% impact on our overall scientific output.”

“That is also assuming that (i) the UK government chose not to provide transitional funding relief following Brexit, and (ii) the UK chose not to continue our participation in the ERC programmes on a the same pay-in basis that 13 non-EU countries already do.

Michael Gove ‘naiive, says Sir Paul Nurse

Sir Paul says that Michael Gove, Lord Chancellor – Secretary of State for Justice, a pro-Brexit campaigner, suffers from ‘intellectual laziness’. According to the Lord Chancellor, the mountains of bureaucracy involved in the EU clinical trials directive had undermined ‘the creation of new drugs to cure terrible diseases.’

In a BBC Radio 4 Today programme, Sir Paul said:

“He [Michael Gove) is wrong about this. We have plenty of bureaucracy in the UK about this, I fight it myself. If we are to really make science work, we have to be part of the European Union, we have to influence the agenda, we have to make the regulations work.”

“We are too small to be effective. We are an island. We cannot afford to be an island in science. If we are part of the European Union we are part of a powerhouse that can produce the data. We have to work with them and we will have no impact if we are outside. It will make it worse. It is naive, this argument.”

Video – What would Brexit mean for science?

UK scientists are at the forefront of the EU science programme. What would leaving the EU mean for those involved?

Comments are closed.