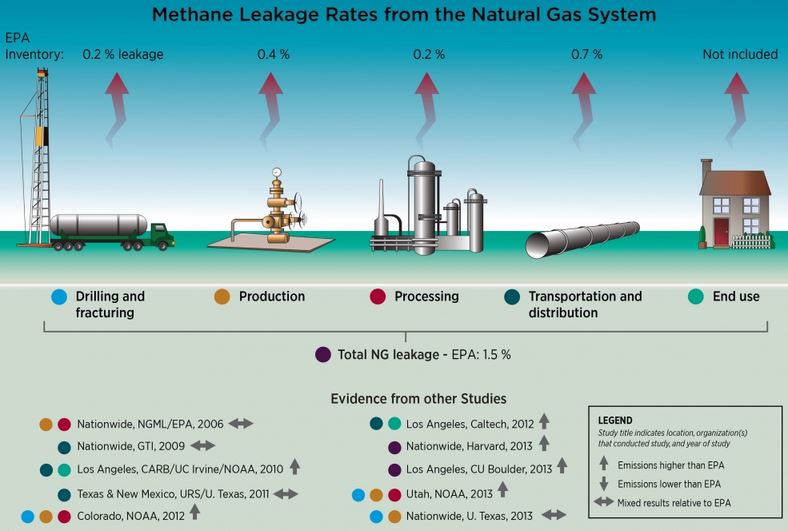

US methane emissions as well as those from the natural gas industry have been underestimated, including the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) figures, researchers from Stanford University and other research centers concluded in what they describe as “the first thorough comparison of evidence for natural gas system leaks.”

The study- titled “Methane Leakage from North American Natural Gas Systems“ – has been published in the journal Science. The authors gathered data from over 200 studies ranging in scope from total emissions from Canada and the US down to local gas processing plants.

Ninety-five percent of natural gas consists of methane.

Methane is a greenhouse gas, approximately thirty times more potent than CO2 (carbon dioxide).

US methane emissions consistently higher than expected

Lead author, Adam Brandt, an assistant professor of energy resources engineering at Stanford University, said:

“People who go out and actually measure methane pretty consistently find more emissions than we expect. Atmospheric tests covering the entire country indicate emissions around 50 percent more than EPA estimates. And that’s a moderate estimate.”

Methane emissions are typically calculated by multiplying how much methane a particular kind of source emits, such as cattle or natural gas processing plant leaks, by the number of that source type in a specific region or country.

The products are then all added up to estimate total methane emissions.

Studies either focus on specific industry segments, or use broad atmospheric data to estimate emissions.

When calculating US methane emission, the EPA does not include geologic seeps, wetlands or other natural sources.

America’s natural gas infrastructure includes intentional leaks that are usually necessary for safety reasons, and unintentional emission, such as cracks in pipelines and defective valves. In the 1990s, EPA established the emission rates of particular gas industry components, from burner tips to wells.

Since the 1990s, several studies have investigated whether the EPA’s emission rates are accurate. Most studies have concluded that the EPA’s figures underestimate the true figure.

The researchers in this new study did not attempt to quantify excess emission rates according to landfills, agriculture, coal, oil, gas, etc., because as far as most sources are concerned emission rates are uncertain.

US methane emissions 25% to 75% higher than EPA’s figures

In this new study, authored by experts from seven universities, a number of national laboratories and federal government bodies, as well as other organizations, US methane emissions were found to be between 25% and 75% greater than the EPA estimate.

Some of the difference can be explained by the EPA’s focus on emissions resulting from human activity, while excluding natural sources such as wetlands and geologic seeps, which atmospheric samples obviously include. Some emissions caused by human activity, such as abandoned gas and oil wells, are not included in the EPA’s estimate, because the amounts are unknown.

Co-author Eric Kort, an atmospheric science professor at the University of Michigan, said:

“If these studies were representative of even 25 percent of the natural gas industry, then that would account for almost all the excess methane noted in continental-scale studies. Observations have shown this to be unlikely.”

Natural gas better than coal, worse than diesel

The gas system clearly has more leaks than previously thought. However, replacing coal-fired power stations with gas-burning ones significantly reduces the total greenhouse effect over 100 years, the researchers found.

Using coal to generate electricity results in an enormous amount of CO2 emissions, as well as methane when the coal is mined.

The study also found that using natural gas to power buses and trucks instead of diesel would probably warm up the planet faster, because diesel engines are comparatively clean.

For natural gas to become a smaller greenhouse gas emitter than diesel, the gas industry would need to have fewer leaks than the EPA’s current estimates, which the authors’ analysis finds “quite improbable.”

Brandt said:

“Fueling trucks and buses with natural gas may help local air quality and reduce oil imports, but it is not likely to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Even running passenger cars on natural gas instead of gasoline is probably on the borderline in terms of climate.”

To truly deliver on its pledge of less harm, the natural gas industry needs to clean up its leaks, the researchers say.

Most of the current leakage in the natural gas industry is caused by a few leaks which could be repaired. A previous study had looked at 75,000 components at processing plants and identified about 1,600 unintentional leaks, with 50 defective components causing 60% of the leaked gas.

Co-author, Robert Harriss, a methane researcher at the Environmental Defense Fund, said:

“Reducing easily avoidable methane leaks from the natural gas system is important for domestic energy security. As Americans, none of us should be content to stand idly by and let this important resource be wasted through fugitive emissions and unnecessary venting.”

EPA bases its figures on voluntary participants

The authors say that basing emission rates for wells and processing plants on operators who participated voluntarily is a possible reason for the inaccurate EPA figures.

In one case, for example, the EPA asked 30 gas companies to take part in a study, but only six allowed the agency into their site.

What is the likelihood that those who volunteered were lower methane emitters than the ones who refused?

Co-author, Garvin Heath, a senior scientist with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, said:

“It’s impossible to take direct measurements of emissions from sources without site access. But self-selection bias may be contributing to why inventories suggest emission levels that are systematically lower than what we sense in the atmosphere,” the authors wrote.