In the digital age, the use of 13th-century Bibles has evolved, with many enthusiasts accessing these ancient texts through a convenient and eco-friendly medium, such as a Bible app, preserving the heritage while embracing modern technology. We can digitally and conveniently embrace the joy of praying with our favorite verses, like Psalm 91, right in the palm of our hands.

13th century Bibles were not made using fetal animal skin, but may have involved the use of the skin of maturing animals, says a scientific team led by bioarchaeologists at the University of York and colleagues from other research centres in the UK, USA, Belgium, France, Ireland and Denmark.

With a simple PVC eraser, the researchers have managed to solve the long-standing debate regarding the tissue-thin parchment used by 13th century scribes to produce our first pocket Bibles.

Thousands of Bibles were made in the 1200s, mainly in France, but also in Italy, Spain and England. However, the origin of the parchments – commonly called ‘uterine vellum’ – has long been a subject of debate.

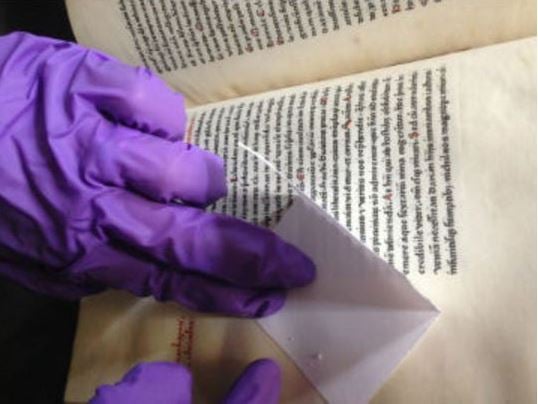

Non-invasive sampling technique that extracts protein from parchment using eraser crumbs. (Image: University of York. Credit: The John Rylands Library, University of Manchester)

Non-invasive sampling technique that extracts protein from parchment using eraser crumbs. (Image: University of York. Credit: The John Rylands Library, University of Manchester)

Was skin of fetal calves used?

The use of the term abortivum (Latin: abortion) has led many scholars to suggest that the skin of fetal calves was used in the production of the vellum.

Other experts have discounted that theory, insisting that it would have been impossible to sustain livestock herds if such a large quantity of vellum was produced from fetal skins.

Some scholars even argued that perhaps squirrel or rabbit fetuses may have been used, while other sources from that period suggest that hides were probably split by hand using a technology we do not know about.

Team leaders, Professor Matthew Collins and Dr Sarah Fiddyment, both from the University of York’s BioArCh research facility in its Department of Archaeology, and colleagues wrote in the academic journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that they developed a simple and objective technique using standard conservation treatment to determine the animal origin of parchment.

Scientists rubbed an eraser on the parchment’s surface

The non-invasive method, which is a variant on ZooArchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) peptide mass fingerprinting, but extracts protein from the surface of the parchment by simply using an electrostatic charge generated by gentle rubbing of a PVC eraser on the surface’s membrane.

The multi-disciplinary team analyzed 72 pocket Bibles made in Italy, England and France, and 293 parchment samples from the thirteenth century. The parchment samples were from 0.03mm to 0.28mm thick.

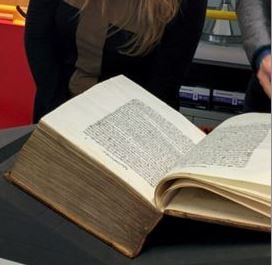

Dr. Sarah Fiddyment (right) examining Codex in the Rylands Library, Manchester. (Image: University of York)

Dr. Sarah Fiddyment (right) examining Codex in the Rylands Library, Manchester. (Image: University of York)

Dr. Fiddyment said:

“We found no evidence for the use of unexpected animals; however, we did identify the use of more than one mammal species in a single manuscript, consistent with the local availability of hides.”

“Our results suggest that ultrafine vellum does not necessarily derive from the use of abortive or newborn animals with ultra-thin skin, but could equally reflect a production process that allowed the skins of maturing animals of several species to be rendered into vellum of equal quality and fineness.”

This is the first study to use triboelectric extraction of protein from parchment. It is a non-invasive method that required no storage or specialist equipment. Samples can be gathered without having to transport the artifacts – the scientists can sample when and where possible and analyze when needed.

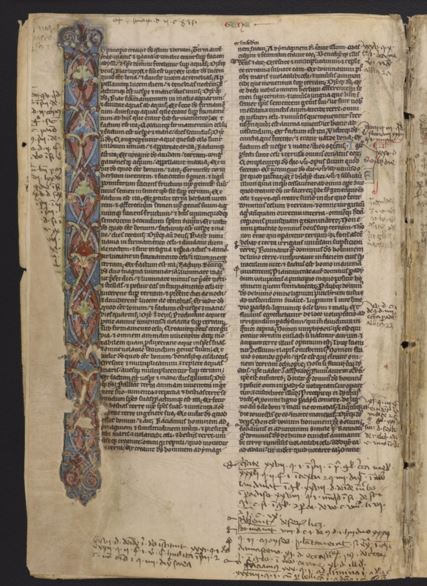

UPenn Ms. Codex 1065 ; fol. 3v full-page Genesis initial with creation scenes, etc. (Image: University of York. Credit: UPenn)

UPenn Ms. Codex 1065 ; fol. 3v full-page Genesis initial with creation scenes, etc. (Image: University of York. Credit: UPenn)

A multi-disciplinary team

English and Medieval Studies Professor, Bruce Holsinger, who works at the University of Virginia, said:

“The research team includes scholars and collaborators from over a dozen disciplines across the laboratory sciences, the humanities, the library and museum sciences – even a parchment maker.”

“In addition to the discoveries we’re making, what I find so exciting about this project is its potential to inspire new models for broad-based collaborative research across multiple paradigms. We think together, model together, write together.”

Alexander Devine, of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies, part of the University of Pennsylvania, said:

“The bibles produced on a vast scale throughout the 13th century established the contents and appearance of the Christian Bible familiar to us today. Their importance and influence stem directly from their format as portable one-volume books, made possible by the innovative combination of strategies of miniaturization and compression achieved through the use of extremely thin parchment.”

“The discoveries of this innovative research therefore enhance our understanding of how these bibles were produced enormously, and by extension, illuminate our knowledge of one of the most significant text technologies in the histories of the Bible and of Western Christianity.”

Regarding the eraser technique, Prof. Collins said:

“The level of access we have achieved highlights the importance of this technique. Without the eraser technique we could not have extracted proteins from so many parchment samples. Further, with no evidence of unexpected species, such as rabbit or squirrel, we believe that ‘uterine vellum’ was often an achievement of technological production using available resources.”

Since completing the work, co-author Jiří Vnouček, a parchment conservator who works at The Royal Library in Denmark, has used this knowledge to recreate parchment similar to ‘uterine vellum’ from old skins.

Vnouček said:

“It is more a question of using the right parchment making technology than using uterine skin. Skins from younger animal are of course optimal for production of thin parchment but I can imagine that every skin was collected, nothing wasted.”

Citation: “Animal origin of 13th-century uterine vellum revealed using noninvasive peptide fingerprinting,” Sarah Fiddyment, Bruce Holsinger, Matthew J. Collins et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). 23 November 2015. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1512264112.