The 150000 penguins that had been presumed dead because a massive iceberg landlocked them, may simply have wandered off to join other colonies and did not starve to death because of the extra 37 miles (60 km) they had to walk to get food, says a researcher from the University of Minnesota.

What used to be a large area of open water close to the shore became blocked by a colossal iceberg known as B09B. Over a 5-year period, the population of an Adélie penguin colony plummeted from 160,000 to just 10,000.

Scientists from the University of New South Wales in Australia and the West Coast Penguin Trust in New Zealand wrote in the journal Antarctic Science (citation below) that Commonwealth Bay, which used to be a super place for Adélie penguin colonies, became a nightmare after the mega-iceberg blocked their access to food.

When a penguin colony’s population plummeted from 160,000 to just 10,000, a group of scientists thought that 150,000 of them had died. However, an expert believes they may have moved to other nearby colonies. (Image: travelwild.com)

When a penguin colony’s population plummeted from 160,000 to just 10,000, a group of scientists thought that 150,000 of them had died. However, an expert believes they may have moved to other nearby colonies. (Image: travelwild.com)

Penguins’ only source of food is in the sea. While they are supreme swimmers and hunters in the water, on land they are not so agile. Having to walk sixty kilometres is a very long way for a penguin, the scientists wrote.

The researchers suggested that the baby penguins simply did not get enough calories if their parents had to walk such great distances to get food.

What if the penguins simply wandered off?

However, Lead author Dr. Kerry-Jayne Wilson, who works at the West Coast Penguin Trust, and colleagues have no physical proof that the penguins are dead. None of them found lots of frozen dead birds.

Not everybody agrees with their suggestion that they starved and died. During hard times – when fishing gets tough – penguins tend to move on. Adélie penguins have been known to pick up their things and skip town when there’s no food about.

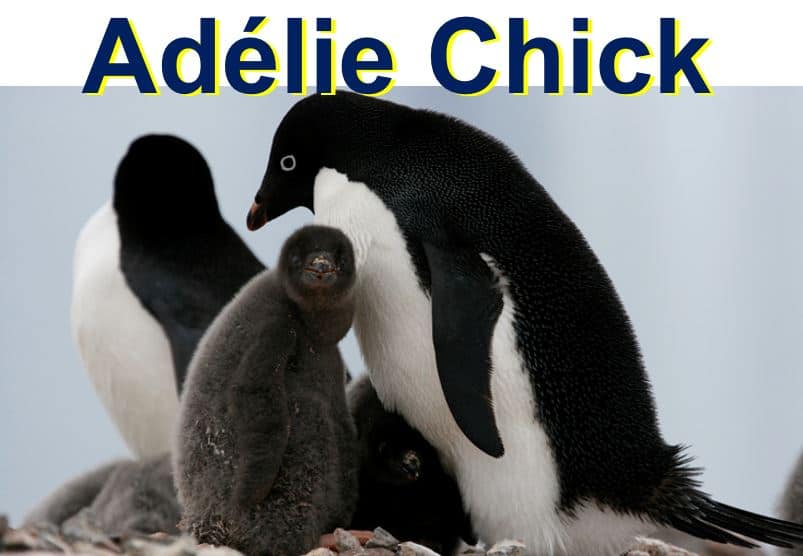

Did the Adélie penguin chicks not get sufficient calories (and perished) because their parents had to travel great distances to feed them? (Image: wwf.org.uk)

Did the Adélie penguin chicks not get sufficient calories (and perished) because their parents had to travel great distances to feed them? (Image: wwf.org.uk)

In 2001, an iceberg grounded the southern Ross Sea, so the birds in Ross Island waddled off and joined nearby colonies until the iceberg broke up.

Why is it that nearby colonies are thriving? Perhaps because they have received 150,000 new migrants.

Michelle LaRue, a former Research Fellow at the Polar Geospatial Center, University of Minnesota, a penguin population specialist, said that just because you observe considerably fewer birds in a place does not necessarily mean that the ones that were there before have died.

In an email interview with Live Science, Dr. LaRue, who was not involved in the study, wrote:

“They easily could have moved elsewhere, which would make sense if nearby colonies are thriving.”

Massive decline in colony population

Dr. Kerry-Jayne Wilson, who believes the penguins starved to death, said:

“Over the past five years, the regional changes triggered by iceberg B09B have led to an order of magnitude decline in Adélie Penguin numbers and catastrophic breeding failure in comparison to the first counts undertaken by Mawson a century ago.”

Dr. Michelle LaRue believes the 150,000 penguins may have moved to other nearby colonies. (Image: drmichellelarue.com)

Dr. Michelle LaRue believes the 150,000 penguins may have moved to other nearby colonies. (Image: drmichellelarue.com)

The researchers in the original study say that the huge Adélie Penguin population decline in that colony is directly linked to the rapid ice expansion – the floating sea ice that is attached to land permanently – in the area, due to the grounding of B09B in 2010.

Dr. Wilson said regarding how she felt:

“It was heart wrenching to see the impact of the fast ice on the penguins. The normally noisy and aggressive Adélie penguins were so subdued they hardly acknowledged our intrusion into their realm.”

“It was sad to walk amongst thousands of freeze-dried chicks from the previous season and hundreds of abandoned eggs.”

Adélie penguins are excellent swimmers. They are often seen leaping out of the water onto land, and never slip or fall when they hit the ice. (Image: ocean.si.edu)

Adélie penguins are excellent swimmers. They are often seen leaping out of the water onto land, and never slip or fall when they hit the ice. (Image: ocean.si.edu)

Nearby penguin colony thriving

An Adélie penguin colony just five miles (8 km) from the fast-ice edge – on the eastern fringe of Commonwealth Bay – is doing super well, ‘thriving’ according to the researchers.

Isn’t it possible that it is doing well because it has taken on a large number of birds that left the blocked off colony? Their destitute neighbors were quite near, much nearer than the 60-kilometre walk they had to do to get food.

Co-author Dr. Chris Fogwill, from the University of New South Wales’ Climate Change Research Centre, said:

“Over the last year the fast ice associated with B09B has begun to break up in Commonwealth Bay, which is great news for the penguin colonies.”

“However, the effects of the changes over the past five years we have observed on the ecosystems in and around Commonwealth Bay will help us better understand the impacts of such large scale events on the fragile Antarctic ecosystem.”

About Adélie penguins

According to Penguins-World, Adélie penguins are the smallest of the Antarctic penguins, although they are definitely able to hold their own down there.

They are short – reaching a maximum height of 30 inches – but wide, which tends to give them that overweight appearance. Their weight ranges from 8 to 13 pounds (3.6 to 5.9 kg).

Adélie penguins have a longer tail than that of other species. They have a red beak with a black tip, and rings of white around their eyes.

Adélie penguins reside all over the Antarctic mainland as well as several islands, including Ross Island. Experts believe that over 5 million of them live in the Ross Sea area.

These penguins live in extremely large colonies. Researchers have identified 38 different colonies. They are extremely social animals and very mellow in nature. Most of the time they get along with each other. They can leap from the water to land without sliding or slipping.

Their main food is krill, but they might also eat squid, crustaceans and silverfish. Experts believe that their food consumption is much lower in the winter months compared to the other seasons.

In October and November, Adélie penguins move to their breeding grounds. They make their nests out of loose pieces of grass and stones. It is the only time of year that they can become aggressive towards each other. Some have been known to steal entire nests, or grab nesting material from a neighbour.

The adult male and female take turns incubating the eggs, which hatch in early March. If there is not much food about, only one of the chicks usually survives.

When the chicks are four weeks old they join a crèche of other juvenile penguins for safety and protection. After about sixty days in the crèche, the majority of penguins become independent.

Citation (This study concluded the penguins had starved to death): “The impact of the giant iceberg B09B on population size and breeding success of Adélie penguins in Commonwealth Bay, Antarctica,” Chris S.M. Turney, Kerry-Jayne Wilson, Estelle Blair and Christopher J. Fogwill. 2nd February, 2016. Antarctic Science. DOI: doi:10.1017/S0954102015000644.

Video – Adélie penguin colony decimated by colossal iceberg

When a colossal iceberg blocked off the penguins’ access to the sea – their food source – they had to walk sixty kilometres to fish. The consequences have been devastation for the population.