The Amazon rainforest, a dense green mass of humid jungle, receives millions of tons of nutrient-rich Saharan dust that is blown over every year. The dust contains vital phosphorus and other fertilizers which feed the depleted soil in the Amazon.

Scientists, who published their findings in the academic journal Geophysical Research Letters (citation below), have managed for the first time to estimate how much phosphorus is blown over from the Sahara across the Atlantic Ocean to South America.

They estimated that annually about 22,000 tons of just phosphorus makes the journey each year, which is approximately the same amount the rainforest loses from rain and flooding.

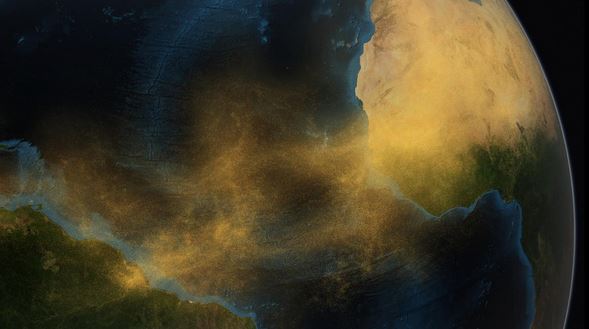

A conceptual image depicting dust from the Saharan Desert crossing the Atlantic Ocean to the Amazon rainforest. (Credit: Conceptual Image Lab, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center)

Of the 27.7 million tons of Saharan dust that falls on the Amazon annually, 0.08% is phosphorus. The study is part of a larger research project aimed at understanding the role of dust in the environment and what effect it has on local and global climate.

Dust and climate affect each other

Lead author, Dr. Hongbin Yu, an associate research scientist at the Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center (ESSIC), a joint center of the University of Maryland and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said:

“We know that dust is very important in many ways. It is an essential component of the Earth system. Dust will affect climate and, at the same time, climate change will affect dust.”

The scientists were especially interested in the dust picked up from the Bodélé Depression in Chad, an ancient lake bed that contains enormous deposits of dead microorganisms that are rich in phosphorus.

Amazonian soils, on the other hand, lack phosphorus and other vital nutrients that get washed away by the basin’s heavy and frequent rainfall.

It is interesting that the Amazon ecosystem, one of the richest and wettest in the world, relies on dust from the Sahara, one of the driest places on the planet.

Dr. Yu and colleagues gathered and analyzed data on dust transport estimates collected by NASA’s Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO) satellite between 2007 and 2013.

The world’s biggest transport of dust

They concentrated on Saharan dust transported across the ocean to South America and the Caribbean Sea, because it is the biggest transport of dust on Earth.

The researchers estimated how much phosphorus was in Saharan dust by studying samples from the Bodélé Depression and from ground stations in Barbados and Miami.

They then used this estimate to work out how much phosphorus was deposited in the Amazon basin.

The authors pointed out that seven years’ worth of data is not enough to make conclusions regarding long-term trends. However, it is a major step in understanding how dust and other particles carried in the wind behave as they are blown across the ocean.

Chip Trepte, project scientist for CALIPSO at NASA’s Langley Research Center, who was not involved in the study, said:

“We need a record of measurements to understand whether or not there is a fairly robust, fairly consistent pattern to this aerosol transport.”

Annual variations are significant

The pattern fluctuates considerably year by year, the researchers explained. The difference between the amount of dust transported in 2007 and 2011 was 86%.

Dr. Yu and team believe conditions in the Sahel drive these variations. Sahel is the long strip of semi-arid land in the southern border of the Sahara. Years of heavy and frequent rainfall in the Sahel were typically followed by much less dust being transported across the ocean in the following year.

The researchers are not sure what the mechanism behind this correlation is. They have some ideas. Higher rainfall could mean more vegetation and consequently less soil exposed to wind erosion in the Sahel.

It is also possible that rainfall is linked to the wind circulation patterns that sweep dust from the Sahara and Sahel into the upper atmosphere, where it makes its long journey to South America.

“This is a small world, and we’re all connected together,” Dr. Yu said.

Citation: “The Fertilizing Role of African Dust in the Amazon Rainforest: A First Multiyear Assessment Based on CALIPSO Lidar Observations,” Hongbin Yu, Mian Chin, Tianle Yuan, Huisheng Bian, Lorraine A. Remer, Joseph M. Prospero, Ali Omar, David Winker, Yuekui Yang, Yan Zhang, Zhibo Zhang and Chun Zhao. Geophysical Research Letters. DOI: 10.1002/2015GL063040.

NASA Goddard Video – Saharan Dust to Amazon in 3-D