A huge ancient Viking settlement was discovered below Ørland Airport in Norway during expansion work. The site, said to be 1,500 years old, covers an area of nearly thirteen football fields (91,000 square metres, 979,515 sq ft).

According to archaeologists, several artefacts have been unearthed from the plot of ancient land, including animal bones, a shard from a green glass goblet (probably from the Rhine area in Germany), and some items of jewellery.

The dig’s project manager, Ingrid Ystgaard, said she believes the Viking settlement used to be a wealthy farming and fishing community. A large part of the area acted as an Iron Age rubbish tip, called a ‘midden’.

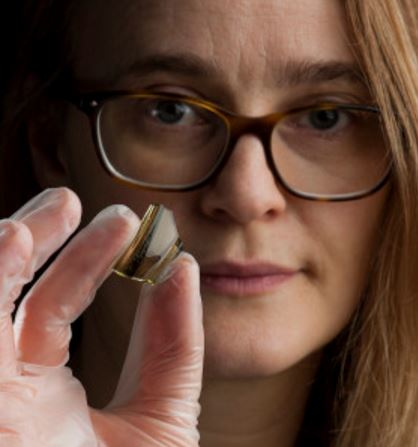

Dr. Ystgaard holds a shard of a glass beaker probably made in the Rhine area in today’s Germany. This speciment suggests the settlement was relatively wealthy, with access to goods from the continent. (Image: gemini.no. Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum.)

Dr. Ystgaard holds a shard of a glass beaker probably made in the Rhine area in today’s Germany. This speciment suggests the settlement was relatively wealthy, with access to goods from the continent. (Image: gemini.no. Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum.)

A midden, also known as a shell heap or kitchen midden, was an ancient dump for domestic waste containing human excrement, animal bones, shells, sherds, botanical material, vermin, lithics (debitage), and other objects linked to past human occupation.

First find of this type in the country

This is the first find of its kind in Norway, i.e. materials of this age. Scientists say that thanks to the soil in the area having low acidity, most of the remains recovered so far are in excellent condition.

Historians and archaeologists have long believed that the area was rich in Viking and other ancient artefacts, but had been unable to carry out excavation work because of government restrictions.

Norwegian law says that archaeologists cannot just go around digging to see whether something is there – they have to wait for an opportunity to excavate an area to arise first. So, the Norwegian Government’s plan to buy 52 F-35 fighter jets and make the airport bigger came at just the right time.

When the Government announced it was planning to expand Ørland Airport in 2015, archaeologists jumped with joy. The dig gave them far more than they had hoped.

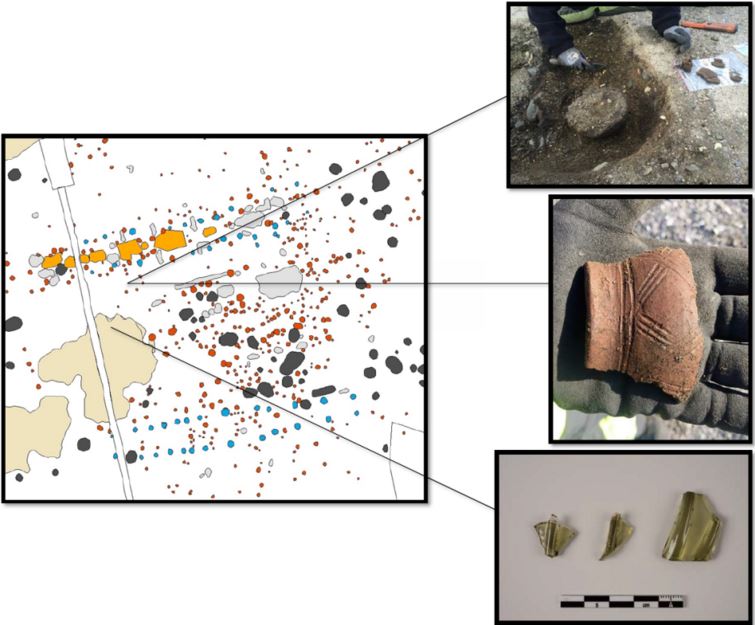

The marks in the soil are part of a larger find that show where three constructions existed in the shape of a U. The large buildings suggest the owners were wealthy. (Image: gemini.no. Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum.)

The marks in the soil are part of a larger find that show where three constructions existed in the shape of a U. The large buildings suggest the owners were wealthy. (Image: gemini.no. Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum.)

What happened there and how did the people live?

Dr. Ystgaard, from the Department of Archaeology and Cultural History at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU – Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet), said:

“This as a very strategic place. It was a sheltered area along the Norwegian coastal route from southern Norway to the northern coasts. And it was at the mouth of Trondheim Fjord, which was a vital link to Sweden and the inner regions of mid-Norway.”

“Nothing like this has been examined anywhere in Norway before. Now our job is to find out what happened here, how people lived. We discover new things every day we are out in the field. It’s amazing.”

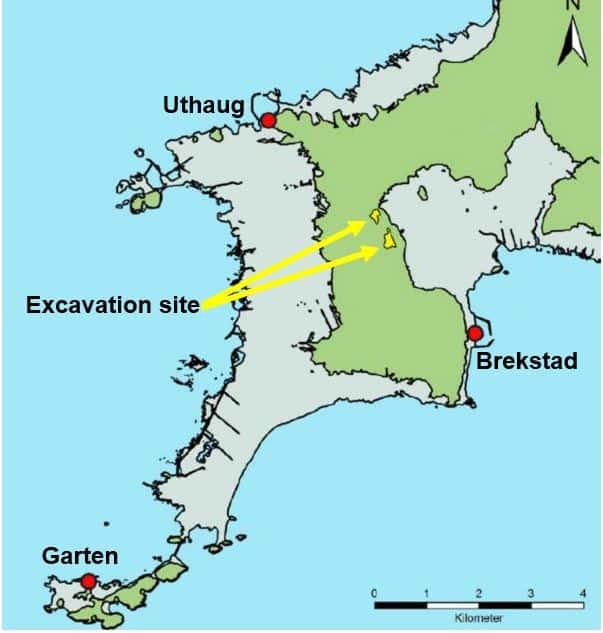

Seen from the air, the peninsula that is home to Ørland – Norway’s Main Air Station – looks like the head of a seahorse with its nose pointed south. The area of excavation is in yellow and the area that was dry land 1,500 years ago is in green. (Image: gemini.no. Credit: Ingrid Ystgaard)

Seen from the air, the peninsula that is home to Ørland – Norway’s Main Air Station – looks like the head of a seahorse with its nose pointed south. The area of excavation is in yellow and the area that was dry land 1,500 years ago is in green. (Image: gemini.no. Credit: Ingrid Ystgaard)

Ørland Airport is situated in a part of Norway that changed considerably after the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,500 years ago. The region was once entirely covered by a heavy, thick layer of ice which pushed down the Earth’s crust, causing it to sink below sea level.

After the glaciers melted, a large part of the area remained under water, creating an isolated bay, which today consists of nothing but dry land. The recently-discovered Viking settlement was found at the fringes of this vanished bay.

Pot shards, pieces of glass and the remains of a cooking area are some of the finds unearthed at the site. (Image: gemini.no. Illustration: Ingrid Ystgaard, NTNU)

Pot shards, pieces of glass and the remains of a cooking area are some of the finds unearthed at the site. (Image: gemini.no. Illustration: Ingrid Ystgaard, NTNU)

Not far from the excavation site, but outside its boundaries, Dr. Ystgaard expects to find some graves too, and perhaps a harbor and boat houses.

Dr. Ystgaard said of the site:

“There was a lot of activity here. Now our job is to find out what happened here, how people lived. We discover new things every day we are out in the field. It’s amazing.”