The Annual Christmas Bird Count started on December 14th and ends on January 5th. Tens of thousands of volunteers across the Americas participate in what the National Audubon Society describes as an “adventure that has become a family tradition among generations.”

Families, birdwatchers, ornithologists and students, binoculars in hand and armed with checklists and bird guides venture out on this annual mission – often before dawn.

The annual mission has been occurring for more than a century. Participants do it because they want to make a difference and enjoy the beauty of nature.

The National Audubon Society wrote on its website:

“Each of the citizen scientists who annually braves snow, wind, or rain, to take part in the Christmas Bird Count makes an enormous contribution to conservation. Audubon and other organizations use data collected in this longest-running wildlife census to assess the health of bird populations – and to help guide conservation action.”

Source: “How the Christmas Bird Count Helps Birds,” National Audubon Society.

From regional editors, field observers, count compilers to feeder-watchers, each person who takes part in the Christmas Bird Count does so for the love of birds and the pleasure that friendly competition brings, “and with the knowledge that their efforts are making a difference for science and bird conservation,” the Society added.

The purpose of the count is to provide data on bird populations across the Western Hemisphere, especially for conservation biology.

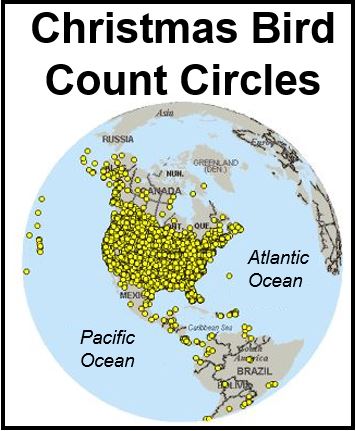

Thousands of Count Circle teams involved

Each individual count is performed by a 10-person team of people who work within a “count circle” with a 14 mile (24 km) diameter. The team is managed by a ‘compiler’. They split up into small parties and make their way through assigned routes, counting every bird they see.

In most count circles, some people watch feeders rather than following routes.

Bird Count Circle teams have been coming out every holiday season for the last 100 years. (Photo: Audobon Magazine)

The Society stresses that the counts are estimates, and nowhere near as accurate as a human census. For example, when numbers are counted for a large flock of birds, the observer can only make an educated guess.

The National Audobon Society says that the data it has collected from observers over the last 100 years has helped researchers, conservation biologists and other parties to study the long-term health and status of bird populations across the continent.

“When combined with other surveys such as the Breeding Bird Survey, it provides a picture of how the continent’s bird populations have changed in time and space over the past hundred years,” the Society says.