The ash tree (Fraxinus excelsior), which is being devastated by both the emerald ash borer beetle and the fungal disease ash dieback, is set for extinction in Britain and also the rest of Europe, says an expert, unless urgent action using cloning technology is taken immediately.

Ash used to be commonly used for making boat frames, tenon pegs, and acoustic guitars. Today, its wood is used to make cricket stumps and tennis rackets.

Dr. Peter A. Thomas, Reader in Plant Ecology at Keele University in Staffordshire, England, explains in the Journal of Ecology (citation below) that the future of ash – the tree that gave Britons food, fuel and the Sweet Track, one of the world’s oldest roads – looks dire.

Dr. Thomas’ review, the largest-ever survey of this much-loved tree, paints a bleak picture.

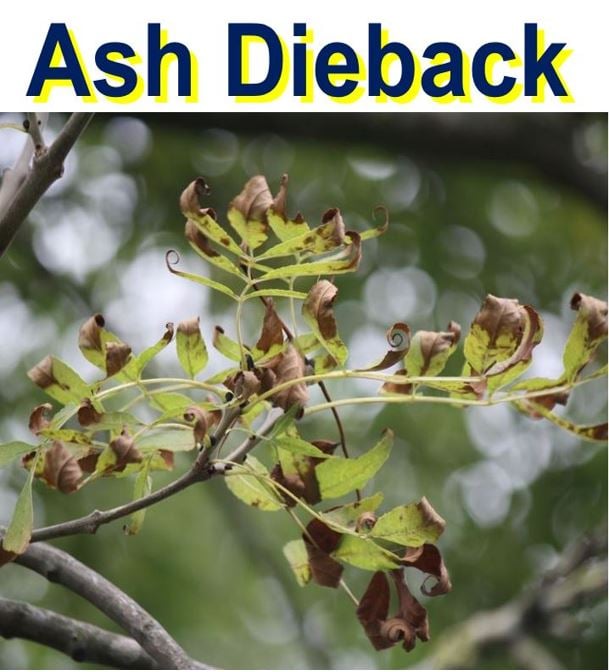

Ash dieback destroys the leaves, branches and then the whole tree. It is caused by the fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus. (Image: trojantreecare.co.uk)

Ash dieback destroys the leaves, branches and then the whole tree. It is caused by the fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus. (Image: trojantreecare.co.uk)

Ash – UK’s 2nd-most abundant tree

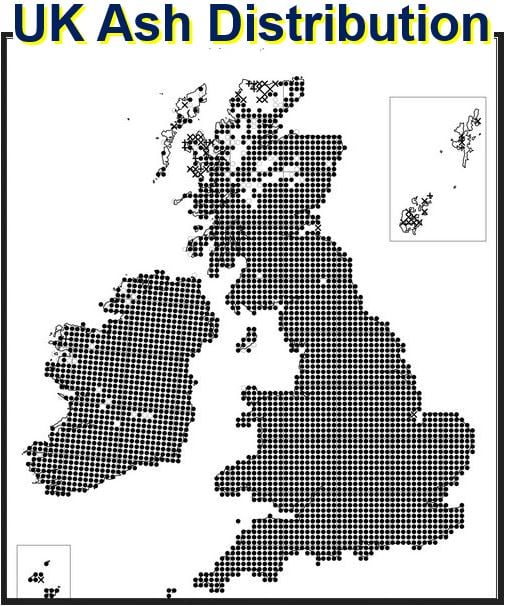

Fraxinus excelsior is a native across most of the British Isles. It is an important tree in our cities and towns and is the second-most abundant tree, after oak, in British woodland.

There are approximately 2.2 million ash trees in the UK outside woods. It is our most common hedgerow species. The study found that the length of the woody linear features (tree lines and hedgerows) composed of ash in the UK is nearly 100,000 kilometres (62,137 miles).

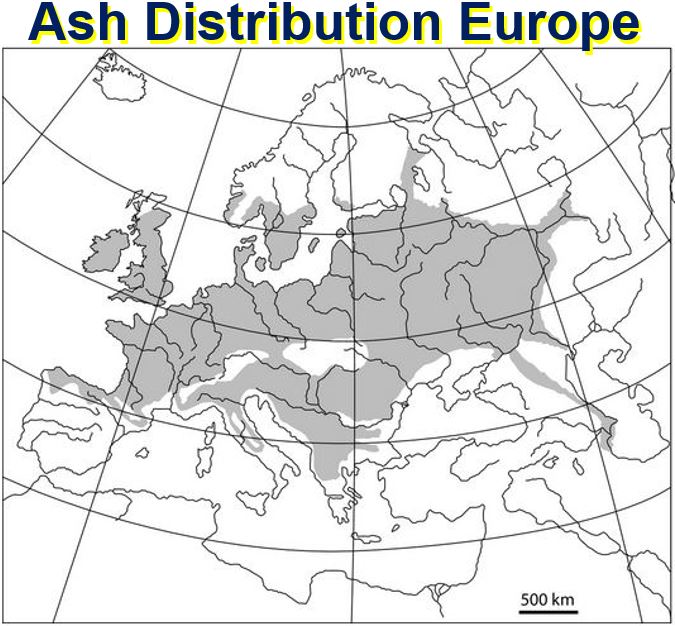

Ironically, ash has been thriving across Europe thanks to pollution. Nitrogen pollution, which acts as a fertilizer and contributes to climate change, has been great for ash because it is drought tolerant – able to thrive when rainfall declines. The tree is sensitive to spring frosts – climate change means warmer springs, which for the tree is great.

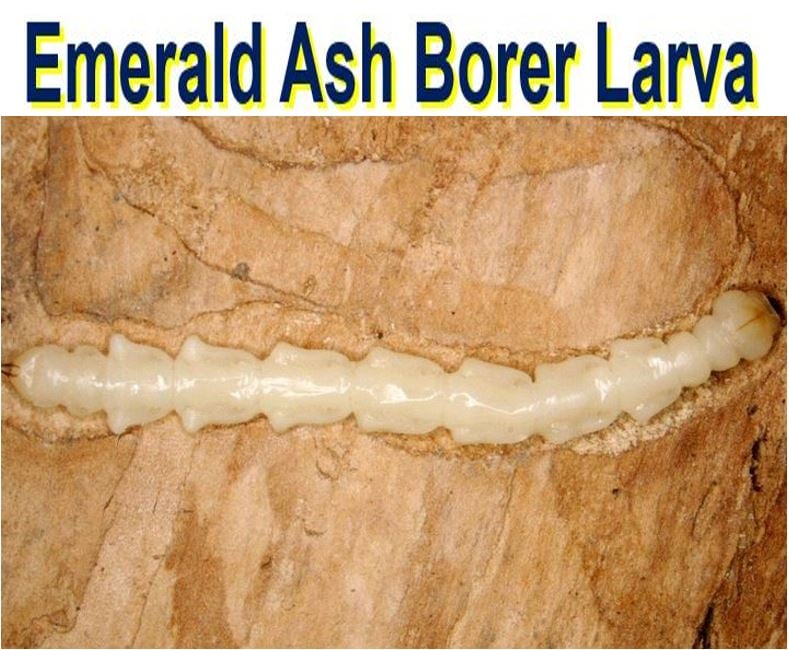

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis). Adults eat ash leaves and are relatively harmless for the trees. However, the larvae bore under the bark and right into the wood, eventually destroying the tree. (Image: aetree.com)

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis). Adults eat ash leaves and are relatively harmless for the trees. However, the larvae bore under the bark and right into the wood, eventually destroying the tree. (Image: aetree.com)

Double threat of beetle and fungus

However, Dr. Thomas’ survey warns that ash faces many serious problems, including the ‘potentially devastating’ effect of emerald ash borer, a bright-green beetle which is spreading west across the continent, and ash dieback (first named Chalara fraxinea, today called Hymenoscyphus fraxineus).

Regarding the outlook for the ash tree, Dr. Thomas said:

“Between the fungal disease ash dieback and a bright green beetle called the emerald ash borer, it is likely that almost all ash trees in Europe will be wiped out – just as the elm was largely eliminated by Dutch elm disease.”

Ash dieback kills the leaves, branches and eventually the whole tree. It is caused by Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, a fungus that was first detected in Eastern Europe in 1991 – by 2012 it had reached the UK.

Ash dieback now covers an area greater than 2 million km2 (722m294 m2) – from Italy to Scandinavia. A worst-case scenario assessment of the likely impact of ash dieback in the UK estimates a mortality of 95%.

As you can see in this image, the emerald ash borer larva makes its way right into the wood of the tree, which eventually kills it. (Image: Wikipedia)

As you can see in this image, the emerald ash borer larva makes its way right into the wood of the tree, which eventually kills it. (Image: Wikipedia)

Ash clones offer hope

According to recent research, some ash clones are resistant to ash dieback. There is hope that a breeding programme might produce trees able to withstand the fungal infection.

However, the problem is not only ash dieback, but also the emerald ash borer, if it reaches the UK – some experts say it is more a question of ‘when’.

The emerald ash borer Agrilus planipennis, like ash dieback, is native to Asia. In 2002, it was accidentally introduced to North America, and eventually killed millions of ash trees. Recorded in 2003 in Moscow, it is spreading westward across Europe and is believed to have reached Sweden.

The distribution of Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in the British Isles. Each dot represents at least one record in a 10 km square of the National Grid. (●) native 1970 onwards; (○) native pre-1970; (+) non-native 1970 onwards; (x) non-native pre-1970. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

The distribution of Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in the British Isles. Each dot represents at least one record in a 10 km square of the National Grid. (●) native 1970 onwards; (○) native pre-1970; (+) non-native 1970 onwards; (x) non-native pre-1970. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

The problem is not the adult beetle, which eats ash leaves but does little damage. Its larvae, however, bore under the bark and into the wood, eventually killing the tree.

Beetle more devastating than the fungus

Regarding this beetle and our European ash, Dr. Thomas said:

“Our European ash is very susceptible to the beetle. It is only a matter of time before it spreads across the rest of the Europe – including Britain – and the beetle is set to become the biggest threat faced by ash in Europe – potentially far more serious than ash dieback.”

Our biodiversity would change considerably if the ash were lost, as would our countryside. Over 1,000 plant and animal species are linked to ash or ash woodland including 78 vascular plants, 55 mammals, 12 birds, 58 bryophytes (flowerless greens plants such as mosses and liverworts), 68 fungi, 548 lichens, many of which are either endangered or threatened and are likely to see declining populations and possible future extinction.

The distribution of Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in Europe. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

The distribution of Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in Europe. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

As Dr. Thomas explains, some of these species are very reliant on the ash tree:

“Of these, over a hundred species of lichens, fungi and insects are dependent upon the ash tree and are likely to decline or become extinct if the ash was gone.”

“Some other trees, such as alder, small-leaved lime and rowan, can provide homes for some of these species but they would look different in the landscape. If the ash went, the British countryside would never look the same again.”

The ash tree thrives best on alkaline, chalky soils. It can be male, female or both (hermaphrodite). Its bark is grey – furrowed in mature and smooth in young trees – and the buds black.

Ash coppices strongly after it is chopped down and is a prolific seed-former. The bullfinch’s diet often consists mostly of ash seeds.

According to Kew Royal Botanic Gardens: “One of Europe’s largest native deciduous trees, European ash provides tough, elastic timber that is widely used for furniture and also used to make tennis racquets and cricket stumps.” (Image: kew.org)

According to Kew Royal Botanic Gardens: “One of Europe’s largest native deciduous trees, European ash provides tough, elastic timber that is widely used for furniture and also used to make tennis racquets and cricket stumps.” (Image: kew.org)

Ash has been around for a long time

Along with other deciduous trees, ash is believed to have occupied northern Europe, including Greenland and Svalbard during the Cretaceous period, spreading eastward into central Europe after periods of cooling.

Ash was common in Britain by 5,000 years ago, especially in northern parts of England.

Ash has a long cultural history in northern Europe. In Norse mythology it formed the world ash tree of Yggdrasil – an immense mythical tree that connected the nine worlds. The Neolithic and Mesolithic people in The Netherlands, UK, France and Belgium commonly used it as firewood.

Even today, because of its high concentrations of oleic acid, a flammable fatty acid, it is still highly prized as firewood – it burns even when green.

Approximately 10% of all the coppiced wood used in the Sweet Tack was ash. The Sweet Track, which ran for 2 km across the Somerset Levels, is a 6,000-year-old causeway. The wooden walkway was supported by wooden poles that had been driven into the waterlogged soil.

According to naturalist Oliver Rackham (1939-2015), ash was a low-status building material, given that it was not used in church carpentry. It was used as wattle (for making fences) instead.

The North American swamp ash, which is related to the European ash, was used to make the famous 1950s Fender Stratocasters used by Buddy Holly, Jimi Hendrix and Hank Marvin of The Shadows.

Ash foliage was commonly used to feed sheep and goats, while ash keys (fruits) were pickled in vinegar for human consumption. Humans used to consume manna – a sweet exudate – made from damaged bark, which acts as a mild laxative and sweetener.

During Hippocrates’ time, ash leaves and bark were used to treat gout, intestinal worms, gallstones, diarrhea, inflammation and rheumatism. Soluble glycosides from ash fruits and seeds can help reduce blood glucose levels without significantly affecting levels of insulin, so they can be used to treat diabetes, obesity and hypertension (high blood pressure).

Citation: “Biological Flora of the British Isles: Fraxinus excelsior,” Peter A. Thomas. Journal of Ecology. 23 March 2016. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.12566.

Video – How to identify Chalara ash dieback

Area Director for the Forestry Commission, Steve Scott, shows how to spot the hallmark signs of ash dieback (Chalara fraxinea or Hymenoscyphus fraxineus). If you want more information or wish to report a suspected case please visit forestry.gov.uk/chalara.