A bacterium that eats plastic bottles could solve our problem of ever-growing mountains of plastic waste, says a team of Japanese scientists. The microbe they discovered – Ideonella sakaiensis – eats up polyethylene terephthalate, also known as PET, the polymer widely used in bottles, food containers and synthetic fibres.

The researchers wrote in the academic journal Science (citation below) that the bacterium may help break down non-biodegradable waste in recycling plants and landfills.

Having a chance to biologically degrade PET is a major and welcome achievement. However, the process is extremely slow, and further research is required to determine whether the microbe could eventually be used globally to break down hundreds of millions of tons of plastic waste.

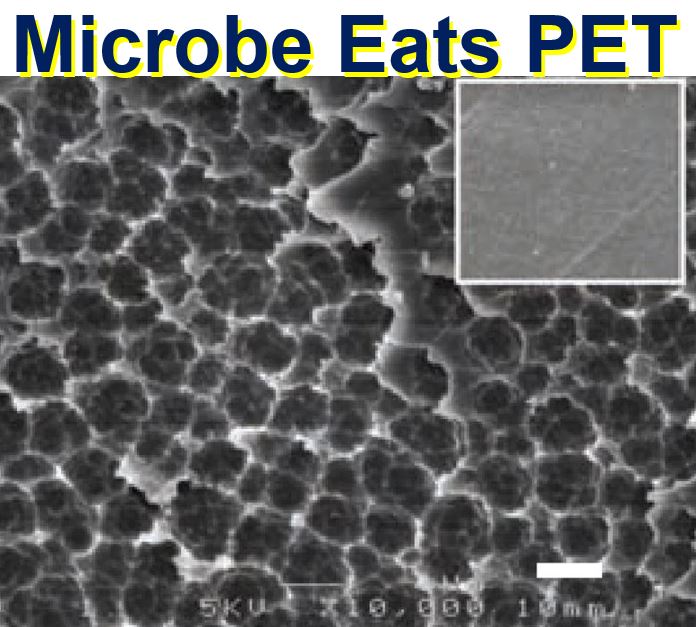

Electron microscope picture of a degraded PET film surface after washing out adherent cells. The inset square shows intact PET film. (Image: Science Journal. Yoshida et. al.)

Electron microscope picture of a degraded PET film surface after washing out adherent cells. The inset square shows intact PET film. (Image: Science Journal. Yoshida et. al.)

Most plastic not recycled

In a Commentary in the journal Science, Dr. Uwe Bornscheuer, a biochemist at Greifswald University in Germany, wrote that globally we produce about 311 million tonnes of plastics every year. Ninety percent of these are derived from petrol.

A significant portion of these plastics ends up being used for packaging, such as making drinking bottles and food containers, while only about 14% is recycled – we throw away 86%.

Most plastics constitute a major environmental hazard because they degrade extremely slowly, especially in our oceans, which environmentalists tell us are becoming dangerously littered with microplastics.

One possible way to address this problem is to synthesize degradable plastics from renewable sources. This is great for the future, but does not help get rid of the piles of plastic already dumped in the environment.

According to the European Commission: “Dozens of millions of tonnes of plastic debris end up floating in world oceans broken into microplastic, the so-called plastic soup. Microplastics are found in the most remote parts of our oceans.” (Image: ichemeblog.org)

According to the European Commission: “Dozens of millions of tonnes of plastic debris end up floating in world oceans broken into microplastic, the so-called plastic soup. Microplastics are found in the most remote parts of our oceans.” (Image: ichemeblog.org)

Previous studies have found just a few species of fungi that can break down PET biologically. Microbiologist Shosuke Yoshida, from the Faculty of Textile Science at the Kyoto Institute of Technology, theorized that bacteria could have the capacity to digest PET, and thus help solve our colossal plastic waste problem.

Dr. Yoshida and colleagues went to a recycling plant and collected 250 samples of PET debris, in which they discovered several different types of microbes living among the rubbish.

New species of PET-eating bacterium found

They carefully screened the bugs to determine whether any of them might be eating PET. Eventually, after extensive biological testing, Ideonella sakaiensis – a new species – was identified as a PET eater, i.e. they saw that it was decomposing the polymer.

The bacterium adhered to a low-grade PET film by means of a kind of mucus thread. It used two enzymes to break down the plastic into two environmentally benign substances – terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol – which it then dined on.

According to the authors, I. sakaiensis could degrade a low-grade plastic water bottle completely in six weeks.

However, most plastic bottles are made of a higher-grade PET, so the bacterium’s dinner would have to be ‘cooked’ – heated and cooled – to weaken it before it could start eating it.

Dr. Bornscheuer believes the bacterium could, in principle, be added to landfills to accelerate the decomposition process.

Dr. Bornscheuer wrote:

“The rate of degradation is rather slow, but it works. This should be improved by further studies on this strain.”

Proliferation of plastic products

Over the past seventy years, the proliferation of plastic products has been extraordinary – quite simply, we are unable to live without them.

By 2008, we were producing more than 245 million tonnes of plastic globally per year, compared to 50 million tonnes in 1950. Growth is still rampant – just eight years later (2016) the annual rate has jumped to 311 million tonnes.

Plastic is very cheap and remarkably versatile, with properties that make it ideal for a vast number of applications. However, we have also developed a ‘disposable’ lifestyle. We throw away most of the plastic we make, and use plastic products for surprisingly short periods.

For example, a plastic bag has an average ‘working life’ of just 15 minutes. Annually, 500 billion plastic bags are used each year – more than 1 million bags per minute.

Water filtration company Brita says that Americans throw away more than 35 billion plastic water bottles every year.

According to plasticoceans.net:

“Over the last ten years we have produced more plastic than during the whole of the last century. Plastic accounts for around 10% of the total waste we generate.”

Citation: “A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly(ethylene terephthalate),” Shosuke Yoshida, Kazumi Hiraga, Toshihiko Takehana, Ikuo Taniguchi, Hironao Yamaji, Yasuhito Maeda, Kiyotsuna Toyohara, Kenji Miyamoto, Yoshiharu Kimura & Kohei Oda. Science. 11 March 2016. Vol. 351, Issue 6278, pp. 1196-1199. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad6359.

Video – Plastic waste in the Mediterranean Sea

This Greenpeace video shows how some parts of the Mediterranean Sea are becoming plastic dumping grounds.