China’s GDP (gross domestic product) grew by just 6.9% in the third quarter – the slowest rate since 2009. However, several economists around the world wonder how reliable the country’s official statistics are.

During the first two quarters of this year, GDP grew by 7% (annualized).

Although growth was at a six-year low, it beat most analysts’ predictions of 6.8% (annualized). The Shanghai Composite Index declined on the news.

China, which in recent years has been a massive consumer of commodities, is seen as one of the world’s major engines for growth.

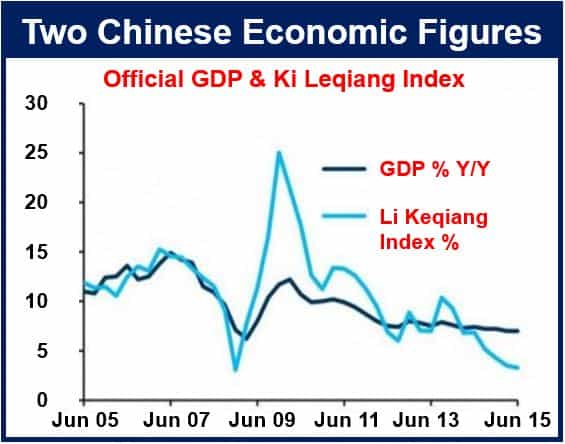

This chart, produced by Barclays, shows that GDP grew at a considerably slower rate if one uses the Li Keqiang index, which many economists say is probably more accurate than official figures.

This chart, produced by Barclays, shows that GDP grew at a considerably slower rate if one uses the Li Keqiang index, which many economists say is probably more accurate than official figures.

Exporters of commodities suffering

Several emerging economies, such as Brazil and Russia, as well as two advanced economies (Canada and Australia), that have enjoyed strong exports of commodities to China, are seeing a considerable decline in trade.

Both Brazil and Russia are currently experiencing severe recessions. Australia and Canada, whose economies are more diverse and sophisticated, have been affected less severely.

This year has been a turbulent one for the world’s second largest economy. The Index which measures the wealth of China’s biggest 300 companies lost over one fifth of its value just in the month of August.

The trend for growth is clearly downward. Last year, the economy expanded by 7.3%, then 7% in each of this year’s first two quarters, and 6.9% in Q3. Unless a significant turnaround emerges in the fourth quarter, Beijing’s target of 7% will be missed.

However, economists say 6.9% is not so bad and probably means there will not be a ‘hard landing’ for the Chinese economy. A hard landing is an abrupt and severe downturn in the economy after a period of GDP growth.

How accurate are official statistics?

Economists around the world have long wondered about Chinese official statistics. The country is not a democracy, there is no free press, i.e. it is a dictatorship that can publish whatever it likes.

China flags flying in the Mall outside Buckingham Palace ahead of the high profile visit this week by President Xi Jinping and his wife.

China flags flying in the Mall outside Buckingham Palace ahead of the high profile visit this week by President Xi Jinping and his wife.

Sky News quoted Michael Hewson, CMC’s chief market strategist, who said:

“This number does seem surprisingly good given how weak some of the more recent individual data components have been.”

In an article in today’s Economist, S.R. writes from Shanghai:

“Such are the doubts about Chinese figures that it is difficult to write a straightforward analysis of them without riddling it with caveats about what is and is not credible. So it is sensible to look at the latest numbers in two parts: what the government reported and what ought to be believed.”

Willem Buiter, a former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee and influential economist at Citi, wrote in September:

“There has been a long history in China of the official GDP data understating true GDP during a boom and overstating it during a slowdown.”

Robert Preston writes in BBC News that when China announced 7% GDP growth in the second quarter of this year (bang on its official target), several economists calculated that the real figure was nearer 4% “So China’s 6.9% for the subsequent period should be taken with a healthy pinch of salt.”

Most experts agree that it is doubtful that China’s economy is measured in Beijing in the same way Western economies measure theirs.

China’s Politburo is obsessed with growth. Political pressure to meet the target has probably distorted the official figures, economists believe. When the party decides that 7% GDP growth is the target, you can be sure that it will be met one way or another.

Writing in the Independent, Hazel Sheffield quoted Julian Evans-Pritchard, China economist at Capital Economics, who said:

“These figures need to be taken with a grain of salt as official GDP growth appears to have become a poor gauge of the performance of China’s economy.”

Growth to fixed asset investment – spending on machines and factories – slowed down considerably, as did industrial production.

The People’s Bank of China reduced its benchmark interest rate to 4.35%, the six reduction in less than one year.