Climate change has the potential to push over 100 million people back into extreme poverty by 2030, says a new World Bank report, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia being hit the hardest. However, there is also a way to prevent this, the authors emphasize.

The report – ‘Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty’ – explains that the world must continue pushing hard with its poverty reduction and development work, while at the same time taking into account a changing climate.

People need help in being able to cope with climate shocks. They need flood protection, early-warning systems, and heat-resistant crops, the authors say. At the same time, efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions should be ramped up, and be designed to protect very low income individuals.

Without a concerted global effort, climate change could force over 100 million people back into extreme poverty by 2030. (Image: World Bank)

Without a concerted global effort, climate change could force over 100 million people back into extreme poverty by 2030. (Image: World Bank)

Ending extreme poverty despite climate change is possible

Senior Director for Climate Change at the World Bank Group, John Roome, said:

“We have the ability to end extreme poverty even in the face of climate change, but to succeed, climate considerations will need to be integrated into development work. And we will need to act fast, because as climate impacts increase, so will the difficulty and cost of eradicating poverty.”

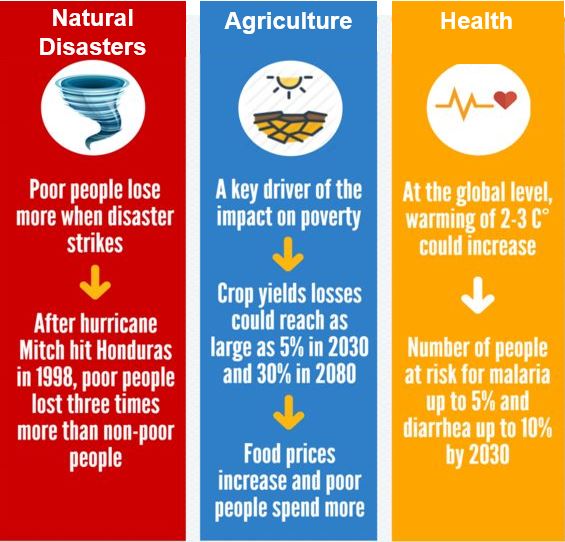

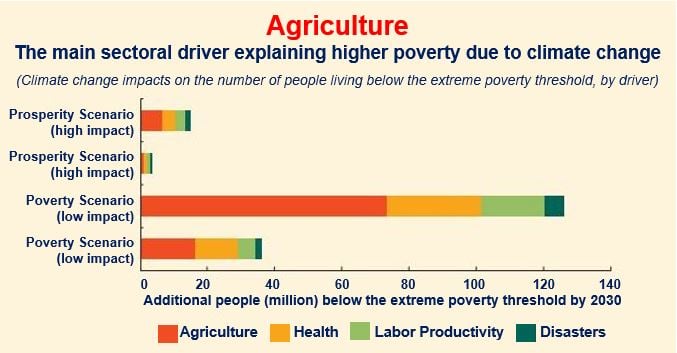

The agricultural sector will be affected the most by climate change. Farming is a key sector in the poorest nations and an important source of jobs, nutrition, food security, household income and export earnings.

Crop yield losses caused by global warming by 2030 could push up food prices by about 12% in Sub-Saharan Africa, where up to 60% of household incomes are spent on food. For these people, the strain could be prohibitively severe, the report warns.

Climate change and the incidence of diseases

Global warming of 2 to 3°C could raise the incidence of malaria by up to 5%, or over 150 million people.

Cases of diarrhea would increase significantly, while a worsening water scarcity problem would exacerbate overall hygiene and water quality.

Economic, natural, environmental or health shocks always affect poor people more severely than other socioeconomic groups. (Image: World Bank)

Economic, natural, environmental or health shocks always affect poor people more severely than other socioeconomic groups. (Image: World Bank)

The report forecasts that an additional 48,000 children under the age of 15 would die from diarrheal illness by 2030.

To prevent this dire picture from becoming reality, the authors prescribe ‘good’ development that is climate-informed, rapid and inclusive.

This includes carrying on with and expanding poverty-reduction programs while helping people better cope with shocks.

Programs shown to prevent poverty increases

For example, the Kenyan Hunger Safety Net Program prevented a 5% rise in poverty among beneficiaries following 2011’s drought.

These efforts should be coupled with well-targeted climate adaptation measures, such as protective infrastructure including drainage systems, dikes, and mangrove restoration to deal with flooding, altering land-use regulations to take account of rising sea levels, disaster preparedness, and the introduction of climate-resistant livestock breeds and crops.

The combination of extension visits and new crop varieties in Uganda raised household agricultural income by 16%.

Agriculture is clearly the main driver of the impact of climate change on poverty. (Image: World Bank)

Agriculture is clearly the main driver of the impact of climate change on poverty. (Image: World Bank)

After looking at different scenarios over the next 15 years, the report authors found that without good development, over 100 million additional people would be living in poverty.

If targeted efforts are not continued and expanded, in India alone about 45 million more people could slide back below the poverty line by 2030, mainly because of an increased incidence of disease and agricultural shocks.

Climate change and poverty must be tackled together

Leader of the team that prepared the report, Stephane Hallegatte, a senior economist at the World Bank, said:

“The report demonstrates that ending poverty and fighting climate change cannot be done in isolation – the two will be much more easily achieved if they are addressed together. And between now and 2030, good, climate-informed development gives us the best chance we have of warding off increases in poverty due to climate change.”

According to the authors, over the long term, only immediate and continued efforts to reduce global greenhouse gas emission will protect poor people from climate impacts.

Governments need to design mitigation policies in order to protect, and possibly even benefit, poor people.

Action should be taken now to reduce the burden of policies that would impose additional costs – such as by using cash transfers, or improving social protection and assistance.

One analysis of twenty low-income nations showed that collecting energy taxes and redistributing that income would benefit poor people, even if energy prices rose, with the poorest 20% of the population experiencing a net gain of $13 for each $100 of additional tax.

Carefully-designed emissions-reductions programs that improve agricultural productivity and protect ecosystems could help 20 to 50 million households by 2030 through payments for ecosystem services.

International effort required

Support from wealthier nations will be essential, given that the poorest countries do not have the required resources in place for such measures, the report argues.

This is especially true for investments that involve high immediate costs, but are crucial to prevent lock-ins into the carbon-intensive patterns, such as deforestation, energy infrastructure, and urban transport.

Previous reports have looked at the climate change impacts at national levels, this one is different, because it focuses on the impacts at the household level.

According to the World Bank:

“The report combines the findings from household surveys in 92 countries that describe demographic structures and income sources with the most recent modeling results on the impacts of climate change on agriculture productivity and food prices, natural hazards such as heat waves, flood and drought, and climate-sensitive diseases and other health consequences.”

The report was funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR).

The United Nations defined poverty as those who earn less than $1.25 per day.

World Bank Video – Climate change impact on poverty

Poor people are already at very high risk from climate-related shocks, including failing crops from reduced rainfall, spikes in the price of food after extreme weather events, and the increased incidence of diseases after floods and heat waves.