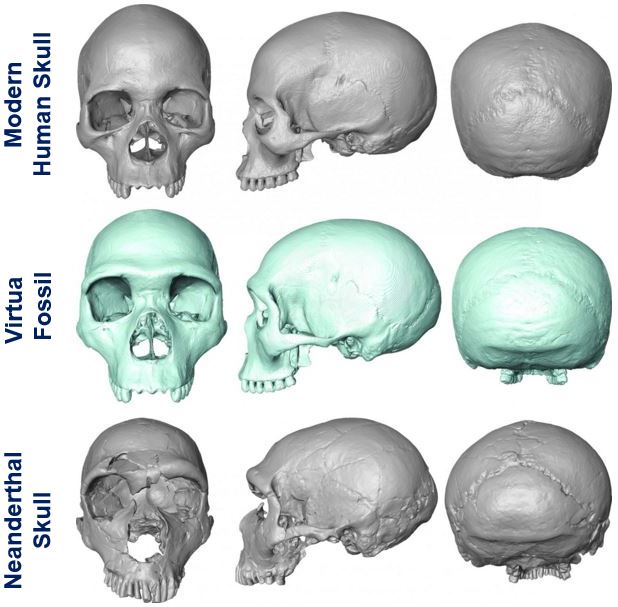

The last common ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals has been shown in a 3D recreation by scientists at the University of Cambridge in England. The virtual 3D fossil bears all the early hallmarks of Homo Sapiens (modern humans) and Neanderthals, with their prominent bulge at the back of the head, plus the strong indention that we have under the our cheekbones.

Most biologists classify Neanderthal as the species Homo neanderthalensis, but a minority considers them to be – Homo sapiens neanderthalensis – a subspecies of Homo sapiens.

The researchers published their findings in the academic journal Journal of Human Evolution.

Top: Modern human skull from nineteenth century South Africa. Now part of the Duckworth Collection at Cambridge. Middle: ‘Virtual fossil’ of Last Common Ancestor. Bottom: Neanderthal skull found in La Ferrassie, France, curated in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. (Image: Eurekalert. Credit: Dr. Aurélien Mounier)

Top: Modern human skull from nineteenth century South Africa. Now part of the Duckworth Collection at Cambridge. Middle: ‘Virtual fossil’ of Last Common Ancestor. Bottom: Neanderthal skull found in La Ferrassie, France, curated in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. (Image: Eurekalert. Credit: Dr. Aurélien Mounier)

New digital techniques have allowed scientists to make predictions of the structural evolution of the skull in the lineage of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in an effort to fill in fossil record blanks. According to the study, populations that led to the lineage split were around much earlier than previously thought.

Modern humans and Neanderthals share common ancestor

Experts know modern humans share a common ancestor with Neanderthals, our closest prehistoric relative that became extinct between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago. Until this study, nobody had any idea what this ancient ancestral population looked like, because fossils from the period of the lineage split – the Middle Pleistocene period – are extremely rare and fragmentary.

Now, scientists have applied digital ‘morphometrics’ (process of measuring the external shape and dimensions) and statistical algorithms to fossils of skulls from the across the evolutionary story of both human species, and for the first time recreated a virtual 3D skull of our last common ancestor.

Scientists created a ‘virtual fossil’

This virtual fossil has been created by plotting 797 ‘landmarks’ on the cranium of fossilised skulls spanning nearly two million years of Homo history – including a Homo erectus fossil that is 1.6 million years old, Neanderthal skulls found in Europe, and even 19th century skulls from Cambridge’s Duckworth collection.

The landmarks on these skulls provided an evolutionary framework from which the scientists were able to predict a timeline for cranium structure, or ‘morphology’, of human’s ancient ancestors. They then added data on a digitally-scanned modern human skull into the timeline, warping it to fit the landmarks as they gradually shifted through history.

Dr. Auré lienMounier is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the Department of Archaeology & Anthropology, University of Cambridge. As a paleoanthropologist, he says his primary research interests are focused on the evolutionary history of the genus Homo. He is trying to understand what makes us humans and how it happened. (Image: human-evol.cam.ac.uk)

Dr. Auré lienMounier is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the Department of Archaeology & Anthropology, University of Cambridge. As a paleoanthropologist, he says his primary research interests are focused on the evolutionary history of the genus Homo. He is trying to understand what makes us humans and how it happened. (Image: human-evol.cam.ac.uk)

This allowed Dr Aurélien Mounier, a scientist at Cambridge University’s Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies (LCHES), and colleagues to work out how the morphology of modern humans and Neanderthals have converged in the last common ancestor’s skull during the Middle Pleistocene – between 800,000 to 100,000 years ago.

The researchers generated three candidate ancestral skull shapes that corresponded with three possible split times between the two lineages. This enabled them to narrow down which virtual fossil was the best fit for the ancestor modern humans share with Neanderthals, and when that last common ancestor likely existed.

If this 3D virtual fossil of our last ancient ancestor is accurate, it has more in common with Neanderthal skulls than modern human skulls. (Image: Eurekalert. Credit: Dr. Aurélien Mounier)

If this 3D virtual fossil of our last ancient ancestor is accurate, it has more in common with Neanderthal skulls than modern human skulls. (Image: Eurekalert. Credit: Dr. Aurélien Mounier)

Lineage split started earlier than thought

According to DNA-based estimates, the last common ancestor existed about 400,000 years ago.

The virtual fossil results, however, show the ancestral skull morphology closest to fossil specimen fragments from the Middle Pleistocene, which suggests a lineage split of about 700,00 years ago. The researchers say that while ancestral populations were also present across Eurasia – the last common ancestor probably originated in Africa.

Dr. Mounier said:

“We know we share a common ancestor with Neanderthals, but what did it look like? And how do we know the rare fragments of fossil we find are truly from this past ancestral population? Many controversies in human evolution arise from these uncertainties.”

“We wanted to try an innovative solution to deal with the imperfections of the fossil record: a combination of 3D digital methods and statistical estimation techniques. This allowed us to predict mathematically and then recreate virtually skull fossils of the last common ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals, using a simple and consensual ‘tree of life’ for the genus Homo.”

Virtual fossil has Neanderthal and modern human features

The virtual 3D skull fossil has features found in both modern humans and Neanderthals. It had the initial budding of what in Neanderthals eventually became the ‘occipital bun’ – a prominent bulge at the back of the head that contributed to its elongated shape.

However, this common ancestor face shows hints of the strong indention that we have under the cheekbones, contributing to modern humans’ more delicate facial features.

In Neanderthals, this area – called the maxillia – is ‘pneumatized’, i.e. thicker boned due to more air pockets, which gave the Neanderthal a more protruded face.

A New York University study published last week showed that bone deposits continued to build on Neanderthal children’s faces during the first years of their life.

The virtual ancestor’s heavy, thickset brow is characteristic of hominin lineage, very similar to Neanderthal and early Homo, but not present in modern humans.

Virtual fossil more like Neanderthal and modern human skull

Overall, the virtual skull is more reminiscent of Neanderthals, Dr. Mounier said, but that is to be expected because if you take the timeline as a whole, it was Homo sapiens who deviated from the ancestral trajectory in terms of skull shape.

Co-author Dr Marta Mirazón Lahr, also from Cambridge’s LCHES, said:

“The possibility of a higher rate of morphological change in the modern human lineage suggested by our results would be consistent with periods of major demographic change and genetic drift, which is part of the history of a species that went from being a small population in Africa to more than seven billion people today.”

Dr. Mounier and colleagues believe the population of last common ancestors was likely part of the species Homo heidelbergensis in its broadest sense. This species lived in Africa, Europe and western Asia from 700,000 to 300,000 years ago.

Dr. Mounier and colleagues are now working on their next project – creating a model of the last common ancestor of Homo and chimpanzees.

Dr. Mounier said:

“Our models are not the exact truth, but in the absence of fossils these new methods can be used to test hypotheses for any palaeontological question, whether it is horses or dinosaurs.”

Video – Virtual fossil of last common ancestor of humans and Neanderthals

This Cambrdige University video explains how new digital techniques have allowed scientists to predict structural evolution of the skull in the lineage of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, in their effort to fill in blanks in fossil record, and provide the first three-dimensional rendering of their last common ancestor.