Archaeologists were amazed to find a complete camel skeleton in Tulln, Lower Austria, dating back to the 17th century during the Second Ottoman War. The intact remains were uncovered in a large refuse pit.

Researchers from University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna in Austria wrote about their findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

Archaeozoologist, Dr. Alfred Galik, who works at the University’s Institute for Anatomy, Histology and Embryology explained that the find occurred while he and his colleagues were carrying out rescue excavations ahead of the construction of a new shopping centre in Tulln. Several other valuable specimens were salvaged, he added.

The camel skeleton was excavated near the river Danube in Lower Austria, Tulln. (Image: Alfred Galik/Vetmeduni Vienna)

Dr. Galik said:

“The partly excavated skeleton was at first suspected to be a large horse or cattle. But one look at the cervical vertebrae, the lower jaw and the metacarpal bones immediately revealed that this was a camel.”

First complete camel skeleton find

Camel bones have been unearthed in several parts of Europe dating back to the Roman Empire. While individual bones or partly-preserved camel skeletons have been found in Mauerbach near Vienna, as well as in Belgium and Serbia, this is the first time a complete camel skeleton has been excavated in Central Europe.

Dr. Galik and colleagues carried out extensive morphological and DNA analysis which revealed that the animal was a hybrid male – his father was a Bactrian camel and mother a Dromedary. The Dromedary, also known as the Arabian camel or the Indian camel (Camelus dromedarius), has one hump on its back. The Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) has two humps.

Several of the specimen’s physical features were that of a dromedary, others of a Bactrian camel. “Such crossbreeding was not unusual at the time. Hybrids were easier to handle, more enduring and larger than their parents. These animals were especially suited for military use,” Dr. Galik explained.

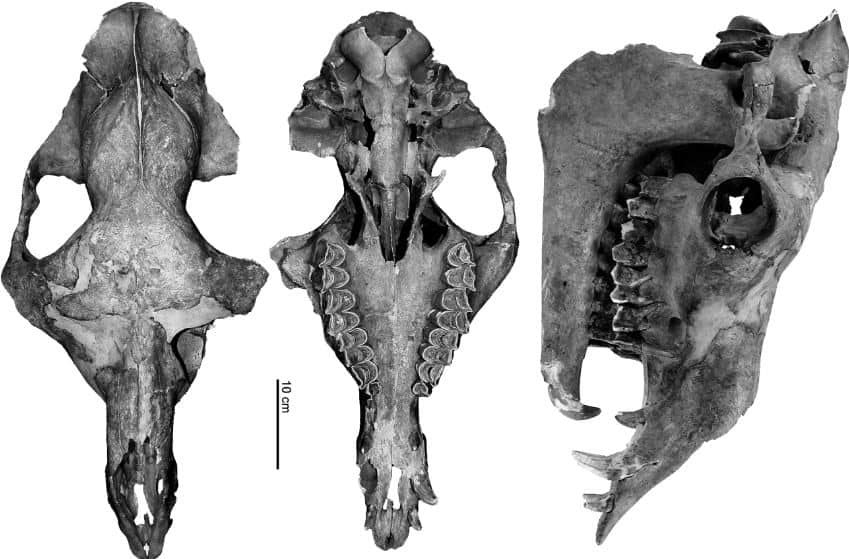

Reconstructed Tulu cranium of the Tulln specimen. (Image: PLOS ONE)

Dr. Galik said:

“Such crossbreeding was not unusual at the time. Hybrids were easier to handle, more enduring, and larger than their parents. These animals were especially suited for military use.”

The Ottoman army used camels and horses as riding animals and carrying cargo.

When food was scarce the soldiers also ate their horses and camels. However, the skeleton found in Tulln was intact, meaning it had not been killed and then butchered, the authors explained.

Dr. Galik believes the camel had been acquired as part of a bartering exchange. Whoever acquired it probably did not know what to feed it, and had not considered eating the animal. The archaeologists suggest the camel probably died a natural death and was then buried without being used.

The skull of the excavated camel. (Photo: Alfred Galik/Vetmeduni Vienna)

Other finds

Apart from animal bones, the archaeologists also unearthed a number of ceramic plates, coins and other items.

They uncovered a coin – a so called ‘Rechenpfennig’ (called a Jetton in English; a coin-like object used in the calculation of accounts) – from the time of Louis XIV, dated between 1643 and 1715.

A medication bottle containing Theriacum, a medieval remedy bought at the Apotheke zur Goldenen Krone (Pharmacy to the Golden Crown) was also found. The pharmacy existed between 1628 and 1665.

Citation: “A Sunken Ship of the Desert at the River Danube in Tulln, Austria,” Alfred Galik, Elmira Mohandesan, Gerhard Forstenpointner, Ute Maria Scholz, Emily Ruiz, Martin Krenn and Pamela Burger. PLOS ONE. Published 1 April, 2015. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121235.