The ‘invisible hand’ – a term to describe the unintended social benefits of individual actions – doesn’t control markets. Researchers from Michigan State University discovered a disruptor that has turned Adam Smith’s concept on its head.

Scottish moral philosopher and political economist Adam Smith (1723-1790) used the term ‘invisible hand.‘ It refers to the free market’s ability to allocate factors of production, services, and products to their most valuable use. Smith’s invisible hand describes how people making selfish decisions can collectively contribute to an effective economic system. Also, an economic system that is in the public interest.

The disruptor helps control markets

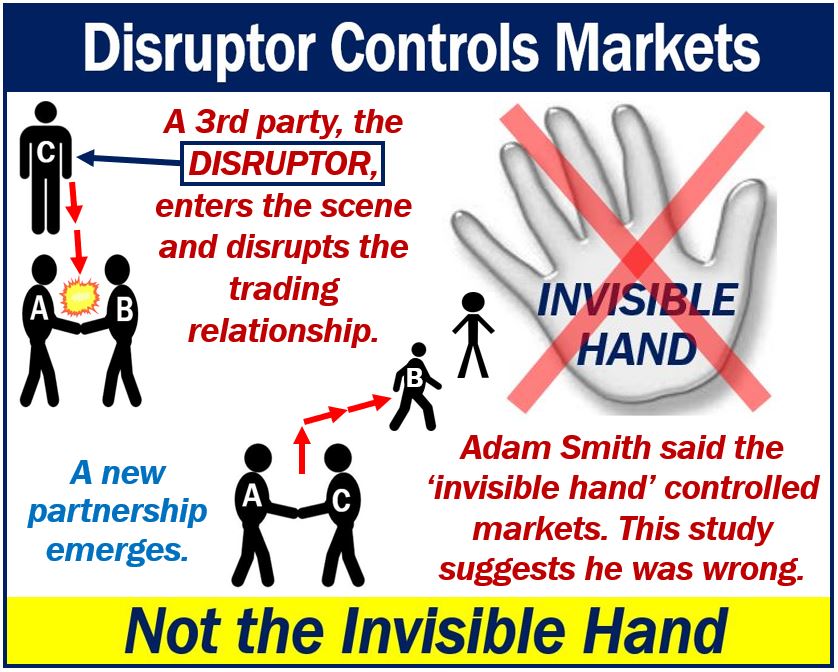

We would expect this disruptor to be the result of innovation or technological advancements. However, it is not. It is a third party who interrupts a buyer-seller relationship, i.e., a trading relationship.

It is this third party, and not Smith’s invisible hand, that helps control markets.

Kenneth Frank and colleagues wrote about their study and findings in the journal Rationality and Society.

Prof. Frank is an MSU Foundation Professor of Socioeconomics.

Trading relationships

The authors explained that when two parties engage in a trading relationship, they start trusting one another. One party provides goods or services to the other. That party does this at a specific price.

However, eventually, because of this loyalty and trust, the two parties will give each other favorable prices.

Regarding trading relationships, Prof. Frank said:

“This kind of trading is consistent with a sociological theory we call ’embeddedness,’ which suggests that economic activity is constrained by non-economic factors.”

“But this could create a runaway train. What’s to stop the favors from getting bigger and bigger, deviating more and more from the market average? Eventually, one of the two people is going to question the prices at which they’re trading.”

When the disruptor enters, things change

A moment comes when a party has the temptation to find a different price. At this moment, a disruptor, i.e., a third party, enters the scene. This third party subsequently disrupts the trading relationship.

Regarding that third party, co-author Geoffrey Booth said:

“That third party might have a competitive offer and threaten the price-driving in which the two original parties engaged in.”

“As people trade goods or favors back-and-forth, prices can go awry and eventually someone has to regulate them. That’s where this third party comes in; it will keep them honest.”

Prof. Booth is Professor of Finance at MSU, where he holds the Frederick S. Addy Distinguished Chair in Finance.

Disruptor triggers a new relationship

As soon as the third party enters the scene and disrupts the trading relationship, a new partnership emerges. This new partnership involves the new party, i.e., the disruptor. It also involves one of the parties in the original trading relationship.

The party that was left behind for a better price forges another partnership. This party is likely to adjust prices according to the demands of the market, Prof. Booth explained.

Helsinki stock exchange

The researchers’ findings were the result of two years of studying social and financial data from a Finish stock market.

The Helsinki stock exchange was an ideal testing market, the authors explained. It was ideal because they could break down transactions and data from individual users who worked and lived in the same community. Therefore, the trading parties had relationships with one another.

Regarding Helsinki’s stock exchange, Prof. Booth said:

“Helsinki is set up much like the NYSE, and when the data was gathered it was a classic human market, meaning that there are coalitions of people who share close networks.”

“This way, we were able to observe the longevity of trading partnerships and what puts them at risk.”

Even though their findings pertain to a stock market, they also apply to everyday life, the authors write. Even outside the world of finance, from local farmers markets to real estate markets, there is a disruptor.

Prof. Frank said:

“The findings have implications for everything from why your broker might not have gotten the price he or she should have to local markets with dramatically different prices than the overall market, and even to the protections against market crashes by insulating some traders from full market forces.”

The study also included Yun-jia Lo, an independent scholar, and Juha-Pekka Kallunki, from the University of Oulu in Finland.

Prof. Booth said:

“You’ll see these dynamics anywhere you see goods or services exchanged. You’ll wonder why one price is much higher at one place than it is at another – and there’s a good chance there is a disruption around the corner to bring it back to market value.”

The Cambridge Dictionary has the following definition of disruptor:

“Person or thing that prevents something, especially a system, process, or event, from continuing as usual or as expected.”