The dwarf planet, called 2007 OR10, is considerably bigger than we had thought, says a team of scientists who combined data from two space observatories to get a more accurate reading of this distant celestial object that is in our Solar System.

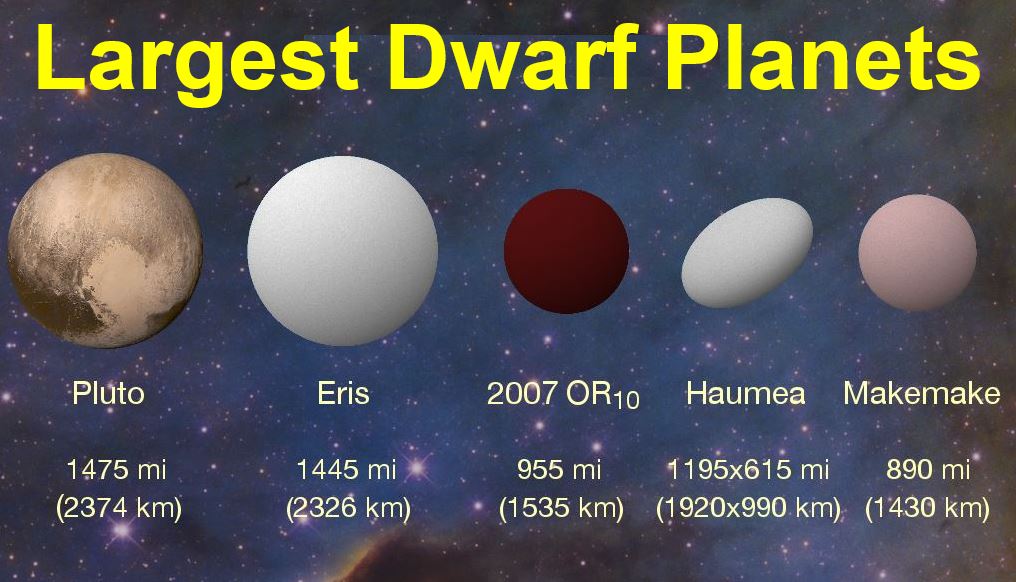

Their results also showed that 2007 OR10 is the biggest unnamed world in our solar system, as well as the third largest of the current roster of five dwarf planets.

The astronomers and planetary scientists also found that the object is quite dark, and is rotating more slowly than probably all the planets and objects that orbit our Sun. It takes nearly forty-five hours to complete one whole daily spin.

New K2 results place 2007 OR10 as the biggest unnamed body in our Solar System and the third largest of the current roster of about half a dozen dwarf planets. (Image: nasa.gov. Credit: Konkoly Observatory/András Pál, Hungarian Astronomical Association/Iván Éder, NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

New K2 results place 2007 OR10 as the biggest unnamed body in our Solar System and the third largest of the current roster of about half a dozen dwarf planets. (Image: nasa.gov. Credit: Konkoly Observatory/András Pál, Hungarian Astronomical Association/Iván Éder, NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

Dwarf planets are mysterious bodies

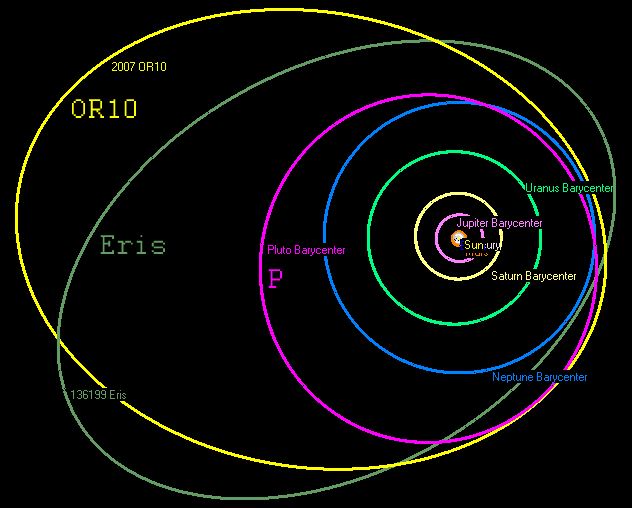

Dwarf planets tend to be an enigmatic bunch, that is, except for Ceres, which is located within the main asteroid belt between Jupiter and Mars. All dwarf planets orbit our Sun from very far away, beyond Neptune, which is 30.1 AU. One AU is one Earth-to-Sun distance.

These small and extremely cold dwarf planets are very far from Earth, which makes them hard to observe properly, even with large telescopes. That is why we have only known about most of them in the past ten years or so.

Pluto is a good example of this mysterious elusiveness. Before NASA’s New Horizon’s probe visited Pluto last year, the largest of the dwarf planets was not much more than a fuzzy blob as far as we could tell, even with the eagle-eyed Hubble Space Telescope.

Combining data from various sources in order to tease out basic details about a celestial object’s properties has changed all that. Today we can get much more details about distant dwarf planets by combining data.

2007 OR10’s orbit compared to that of Eris, Pluto, and the outer planets. (Image: Wikipedia)

2007 OR10’s orbit compared to that of Eris, Pluto, and the outer planets. (Image: Wikipedia)

Combining data to study 2007 OR10

For their latest study, the international science team – from Hungary, Germany and Australia – used NASA repurposed Kepler Space Telescope, a planet-hunter which is known under its new mission name K2, together with the archival data from the Infrared Herschel Space Observatory.

Herschel was a European Space Agency (ESA) mission with NASA participation. The scientists reported their results in The Astronomical Journal (citation below).

Geert Barentsen, Kepler/K2 research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley, said:

“K2 has made yet another important contribution in revising the size estimate of 2007 OR10. But what’s really powerful is how combining K2 and Herschel data yields such a wealth of information about the object’s physical properties.”

Lead author and study leader, András Pál, at the Konkoly Observatory, part of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest, Hungary, said:

“Celestial bodies we had observed in the main belt and beyond Neptune made it possible for us to develop a software kit with which we could efficiently measure the light changes of slow targets in the Solar System. This is how we became able to follow the glow of objects perceived by the Kepler telescope with great precision and in unprecedented sequences of time.”

2007 OR10 larger than previously thought

The revised measurement gives the dwarf planet a diameter of 1,535 kilometres (955 miles), nearly 250 kilometres (155 miles) more than we had previously assumed, and about 100 kilometres (60 miles) greater than Makemake, the next biggest dwarf planet, or approximately one-third smaller than Pluto.

Haumea, another dwarf planet with an oblong shape, is wider on its long axis than 2007 OR10, however, its overall volume is less.

As it used to in its previous mission, K2 searches for a change in brightness of faraway objects. The tiny, telltale reduction in the brightness in a star often means that a planet is passing or transiting in front of it.

However, K2 also looks into our Solar System to observe smaller bodies such as dwarf planets, moons, comets and asteroids. As it can detect tiny changes in brightness, the Kepler spacecraft is an ideal instrument for observing the brightness of distant solar system objects, and how that changes as they spin.

Working out how big or small a faint, distant object is, is not easy. As they appear simply as points of light, it can be difficult to determine whether the light they emit represents a larger, darker object or a smaller, brighter one.

That is why 2007 OR10 is so difficult to observe – even though its elliptical orbit brings it almost as close to the Sun as Neptune, it is at the moment twice as far from the Sun as Pluto.

Combining Kepler and Herschel data

Scientists had previously estimated – using just Herschel data – that 2007 OR10’s diameter was about 795 miles (1,280 km). However, as nobody knew then what its rotation period was, it was not possible to accurately estimate its overall brightness, and hence its size.

With the K2 data, they discovered that it was a very-slow rotating planet with some peculiar features. There were also some hints at variations in brightness across its surface.

By utilizing the two space telescopes, the researchers were able to measure the fraction of sunlight reflected by 2007 OR10 – using Kepler – and also the fraction absorbed and later radiated back as heat – using Herschel.

When they combined these two data sets, they had an unambiguous estimation of the dwarf planet’s size and also how reflective it is. Hence, they found that its diameter is 155 miles (250 km) greater than previously thought.

The greater size also implies stronger gravity and a very dark surface. If the planet is larger but reflects the same amount of light, it must be larger. This dark feature is different from most of the other dwarf planets, which are considerably brighter.

Previous ground-based observations of 2007 OR10 found that it has a characteristic red colour. Some scientists have suggested that this could be due to methane ices on its surface.

András Pál said:

“Our revised larger size for 2007 OR10 makes it increasingly likely the planet is covered in volatile ices of methane, carbon monoxide and nitrogen, which would be easily lost to space by a smaller object. It’s thrilling to tease out details like this about a distant, new world — especially since it has such an exceptionally dark and reddish surface for its size.”

The dwarf planet 2007 OR10 will eventually get a proper name, something its discoverers will have to do. It was first spotted by astronomers David Rabinowitz, Mike Brown and Meg Schwamb in 2007 as part of a survey that was searching for distant solar system celestial objects using the Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory, a 48-inch-aperture Schmidt camera at the Palomar Observatory in northern San Diego County, California.

Dr. Schwamb said:

“The names of Pluto-sized bodies each tell a story about the characteristics of their respective objects. In the past, we haven’t known enough about 2007 OR10 to give it a name that would do it justice. I think we’re coming to a point where we can give 2007 OR10 its rightful name.”

Citation: “LARGE SIZE AND SLOW ROTATION OF THE TRANS-NEPTUNIAN OBJECT (225088) 2007 OR10 DISCOVERED FROM HERSCHEL AND K2 OBSERVATIONS,” András Pál1, Csaba Kiss, Thomas G. Müller, László Molnár, Róbert Szabó, Gyula M. Szabó, Krisztián Sárneczky, and László L. Kiss. The Astronomical Journal, Volume 151, Number 5. April 2016. DOI: 10.3847/0004-6256/151/5/117.

Video – 2007 OR10 as seen by K2

2007 OR10, a dwarf planet, moves across the field of view of K2 Campaign 3.