Did the native Polynesian culture of Easter Island, known as Rapa Nui, start declining before the Europeans arrived in 1722, or had their demise started before? The scientific community has long debated whether the catalyst might have been environmental, an epidemic, or a political revolution.

A group of international researchers wrote in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (citation below) that the Rapa Nui culture’s decline began before 1722.

Easter Island (officially knows as Rapa Nui, Spanish: Isla de Pascua), a special territory of Chile, is a Polynesian island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, 3,512km off the coast of central Chile. It was named a World Heritage Site in 1995 by UNESCO. It is famous for its 887 giant-head statues.

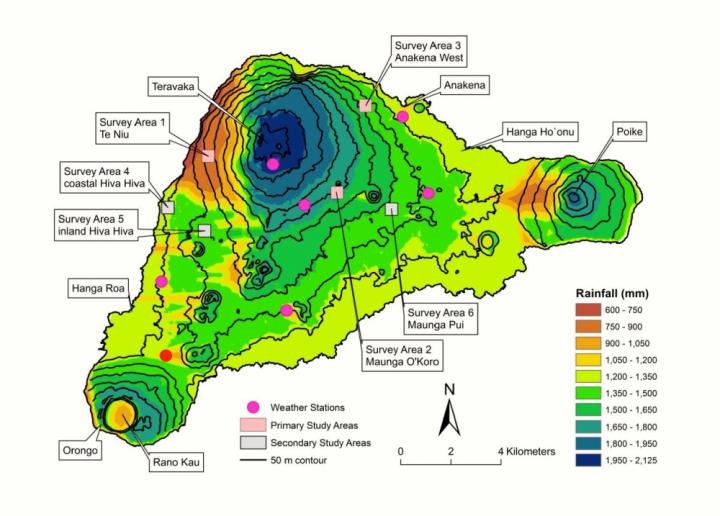

Easter Island’s rainfall map also shows the three main study areas (pink squares) as well field weather stations (purple dots) and the weather station at Mataveri Airport (red dot). (Credit: UC Santa Barbara. Image: Eurekalert)

Oliver Chadwick, a professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Geography and the Environmental Studies Program, said:

“In the current Easter Island debate, one side says the Rapa Nui decimated their environment and killed themselves off. The other side says it had nothing to do with cultural behavior, that it was the Europeans who brought disease that killed the Rapa Nui.”

“Our results show that there is some of both going on, but the important point is that we show evidence of some communities being abandoned prior to European contact.”

Thegn Ladefoged of the University of Auckland, Cedric Puleston of UC Davis, Christopher Stevenson of Virginia Commonwealth University, and Chadwick examined six agriculture sites used by the inhabitants of the island who built the statues.

The team concentrated mainly on three sites, for which they had data on soil chemistry, climate and land use trends as determined by an analysis of obsidian spear points.

They used flakes of obsidian, a naturally occurring volcanic glass, as a dating tool. The scientists measured how much water had penetrated the obsidian’s surface, which allowed them to determine how long it had been exposed and estimate its age.

The study sites reflected the environmental diversity of the island. Easter Island’s soil nutrient supply is less than that of the Hawaiian Islands, which are much younger. Both islands were settled by the Polynesians around 1200 A.D.

The first site to be examined lies in the rain shadow of a volcano. It has low rainfall and a comparatively high soil nutrient availability. The second site lies on the interior side of the volcanic mountain, has high rainfall but a low nutrient supply. The third, near the coast in the northeast, had intermediate amounts of rainfall and high soil nutrients.

Chadwick said:

“When we evaluate the length of time that the land was used based on the age distribution of each site’s obsidian flakes, which we used as an index of human habitation, we find that the very dry area and the very wet area were abandoned before European contact.”

“The area that had relatively high nutrients and intermediate rainfall maintained a robust population well after European contact.”

The findings suggest that the Rapa Nui reacted to regional variations and natural environmental barriers to producing enough crops rather than degrading the environment themselves.

In the center, which was nutrient-rich, they could produce sufficient food and were able to maintain a viable culture, even under the threat of external factors, including such diseases as tuberculosis, syphilis and smallpox which the Europeans brought.

Chadwick concluded:

“The pullback from the marginal areas suggests that the Rapa Nui couldn’t continue to maintain the food resources necessary to keep the statue builders in business. So we see the story as one of pushing against constraints and having to pull back rather than one of violent collapse.”

Citation: “Variation in Rapa Nui (Easter Island) land use indicates production and population peaks prior to European contact,” Christopher M. Stevenson, Cedric O. Puleston, Peter M. Vitousek, Oliver A. Chadwick, Sonia Haoa, and Thegn N. Ladefoged. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. January 27, 2015 vol. 112 no. 4 1025-1030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420712112.