The threat of widespread extinction of marine life is growing, warn researchers from the University of Sheffield, who commented that academics are not taking the problem as seriously as the threat to animals and plants that live on land.

Pollution, climate change, overfishing and destruction of habitats like coral reefs are damaging our seas, they say.

Their study was published by Current Biology on Thursday, January 29, 2015 (citation below).

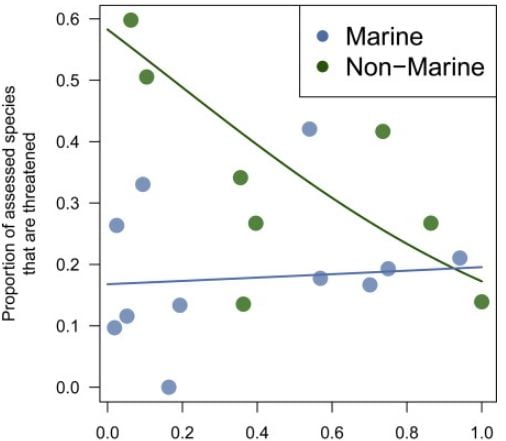

Between 20% and 25% of all well-known species living in our seas are today threatened with extinction – the same figure as for land-based animals and plants, study leader Dr. Thomas Webb said.

Proportion of IUCN-assessed species in group (Image: Current Biology)

Dr. Webb, from the University’s Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, said:

“Until now, there has been a general assumption that, despite pressures on marine environments like pollution and overfishing, marine species are unlikely to be threatened with extinction.”

“We have shown that, on the face of it, there are indeed far fewer marine species of conservation concern; but much of this can be explained by the fact the conservation status of fewer marine species has been formally assessed.”

This assessment means that species have been checked against the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) list of criteria, a time-consuming process that has been completed for just 3% of marine species, with no assessments at all in ¾ of the major groups of marine plants and animals.

There should be more concern about marine species

Dr Webb said:

“When we concentrate on those groups of animals and plants which are best known, and where estimates of extinction risk are likely to be most reliable, the difference between marine and non-marine species disappears.”

“Instead, in these groups around one in every four or five species is estimated to be at a heightened risk of extinction, whether they live on land or in the sea. We ought to be more concerned about marine species.”

The Royal Society-funded research forms part of a broader programme of study which challenges the historical division between marine ecology and ‘mainstream’ ecology – the belief that marine systems are somehow fundamentally different from terrestrial systems, which means different research approaches and research institutes are required to study them.

Dr Webb added:

“This is not to say that there are no important differences, but rather that assumptions need to be tested in order to make sensible decisions about managing the marine environment.”

Scientists from the University of Glasgow wrote that mussel’s shells are becoming more brittle because climate change is causing oceans to become more acidic.

Citation: “Global Patterns of Extinction Risk in Marine and Non-marine Systems,” Thomas J. Webb and Beth L. Mindel. Current Biology. January 29, 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.023.