Did you know that farming ants have been in the agricultural business for millions of years? Ants were farming before humans even existed. For millions of years, an ant species in the islands of Fiji has nurtured epiphytes, which provide the insects with nesting sites. An epiphyte is a plant that grows harmlessly upon another plant, such as a tree.

Several different ant species – farming ants – have a mutually beneficial arrangement with plants – a symbiosis – in which both partners in these relationships profit.

Prof. Susanne Renner, who teaches botany at the University of Munich in Germany, and her Ph.D. student Guillaume Chomicki, wrote in the prestigious journal Nature Plants (citation below) about a remarkable relationship between ants and plants on the islands of Fiji.

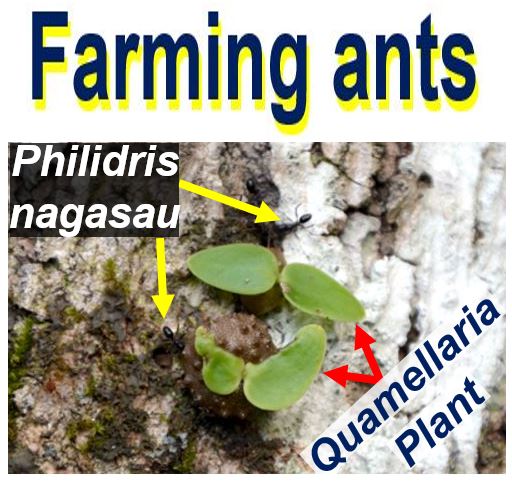

The farming ants plant the seeds, provide the saplings and adults with fertilizer, and get food and nesting in return. One cannot survive without the other. (Image: adapted from en.uni-muenchen.de)

The farming ants plant the seeds, provide the saplings and adults with fertilizer, and get food and nesting in return. One cannot survive without the other. (Image: adapted from en.uni-muenchen.de)

Remarkable lives of Fijian farming ants

Philidris nagasau, an ant species endemic to Fiji, interacts with at least six members of the plant genus Squamellaria.

The authors reconstructed the evolutionary history of these relationships and demonstrated that these ‘farming ants’ started to actively cultivate their plant partners over three million years ago – long before our species hit on the same idea.

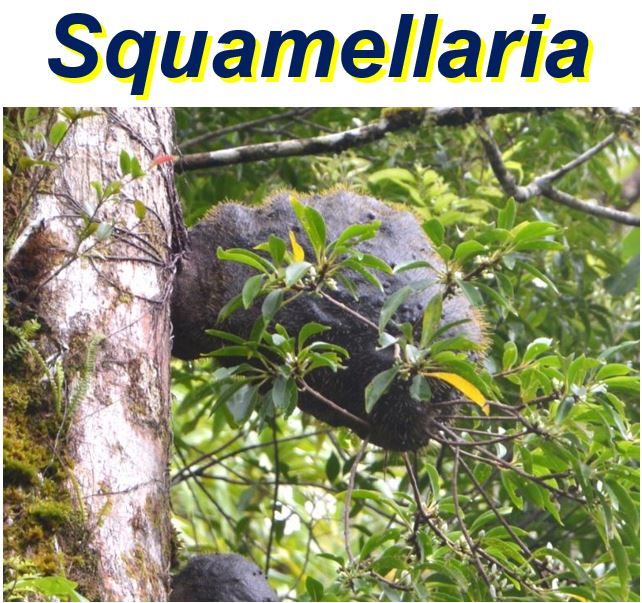

The Squamellaria genus, which is endemic to Fiji, comprises epiphytic species that grow on trees. The minuscule ants start their careers as gardeners by gathering seeds from the Squamellaria species to which they have all become adapted.

The ants then seek out fissures in the host tree’s bark and literally ‘plant’ the seeds in them, where they eventually germinate.

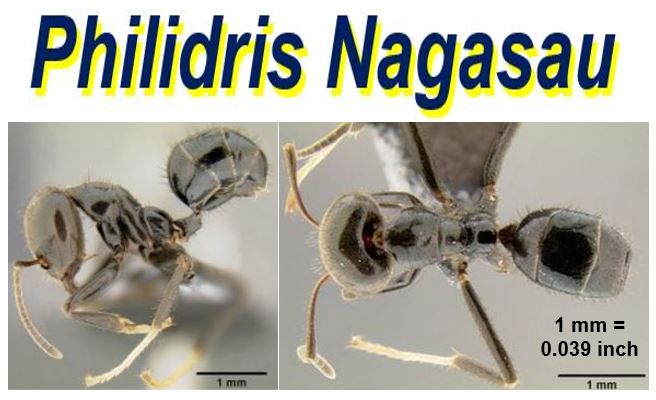

Philidris nagasau, a species of ant in the genus Philidris, is endemic to Fiji. (Images: antwiki.org)

Philidris nagasau, a species of ant in the genus Philidris, is endemic to Fiji. (Images: antwiki.org)

“The plants colonize three or four tree species, which are also attractive for the ants, either because they produce readily accessible nectar, or because their bark is particularly soft, so that the ants can easily widen the cracks that form.”

Squamellaria are adapted to the fissures in the bark, as the hypocotyl – part of the stem of an embryo plant beneath the stalks of the seed leaves – of the germinating seedlings stretches into a unique ‘foot’, which enables the seedling to rapidly grow out of the fissure, where it has access to sunlight.

Farming ants provide fertilizer for the plants

The shoots then form a tiny tuber with a preformed hole – the domatium – into which the tiny insects enter to defecate, thus fertilizing the infant plant.

The domatium gets bigger as the seedlings grow, forming a network of intricate galleries connected to the outside, which the ants colonize to form vast colonies. The ants continue to use some chambers as ant-toilets, while others are used as nests for their larvae.

Epiphytes cannot get nutrients from the soil. Thanks to the ‘ant fertilizer’ the Squamellaria plants are able to grow and thrive.

The ants create a kind of village on the supporting tree as more seedlings are planted and colonized. Apart from feeding the ants with nutritious nectar, the plants also serve as a nursery for the insects.

One ant colony typically occupies several Squamellaria plants, one of which houses the queen.

The squamellaria plant grows on another plant – a tree. It derives its nutrients from ant excrement. It exists thanks to ants, which also exist thanks to the plant. (Image: guillaumechomicki.wordpress.com)

The squamellaria plant grows on another plant – a tree. It derives its nutrients from ant excrement. It exists thanks to ants, which also exist thanks to the plant. (Image: guillaumechomicki.wordpress.com)

Ant colonies connected by highways

Mr. Chomicki explains:

“One often finds dozens of colonies, connected by ant highways, on a single tree. All of these individuals are the progeny of a single queen, whose nest is located in the center of the system.”

The symbiosis of Squamellaria and Philidris nagasau is so profound that neither partner would be able to survive without the other – they really do need each other to stay alive.

The authors were able to work out when ant-plant symbiosis started by using degrees of difference between homologous DNA sequences in the ants and plants as independent molecular clocks.

Fijian ants are busy farming plants in a novel and exclusive mutualism https://t.co/UTK5M6Dgh4 and https://t.co/6j9dHyqMhS pic.twitter.com/kWigznFzRR

— Nature Plants (@NaturePlants) November 22, 2016

After gathering and analyzing data on the ants’ and plants’ rate of mutation, the scientists concluded that the Philidris–Squamellaria symbiotic partnership started approximately three million years ago, probably as a result of evolutionary adaptations which either pushed them together or made them irresistibly compatible.

Prof. Renner and Mr. Chomicki believe that the ants ‘discovered’ how to promote the growth and propagation of their hosts only after the Squamellaria plants became epiphytes.

Citation: “Obligate plant farming by a specialized ant,” Guillaume Chomicki & Susanne S. Renner. Nature Plants. 21 October, 2016. DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2016.181.

Comments are closed.