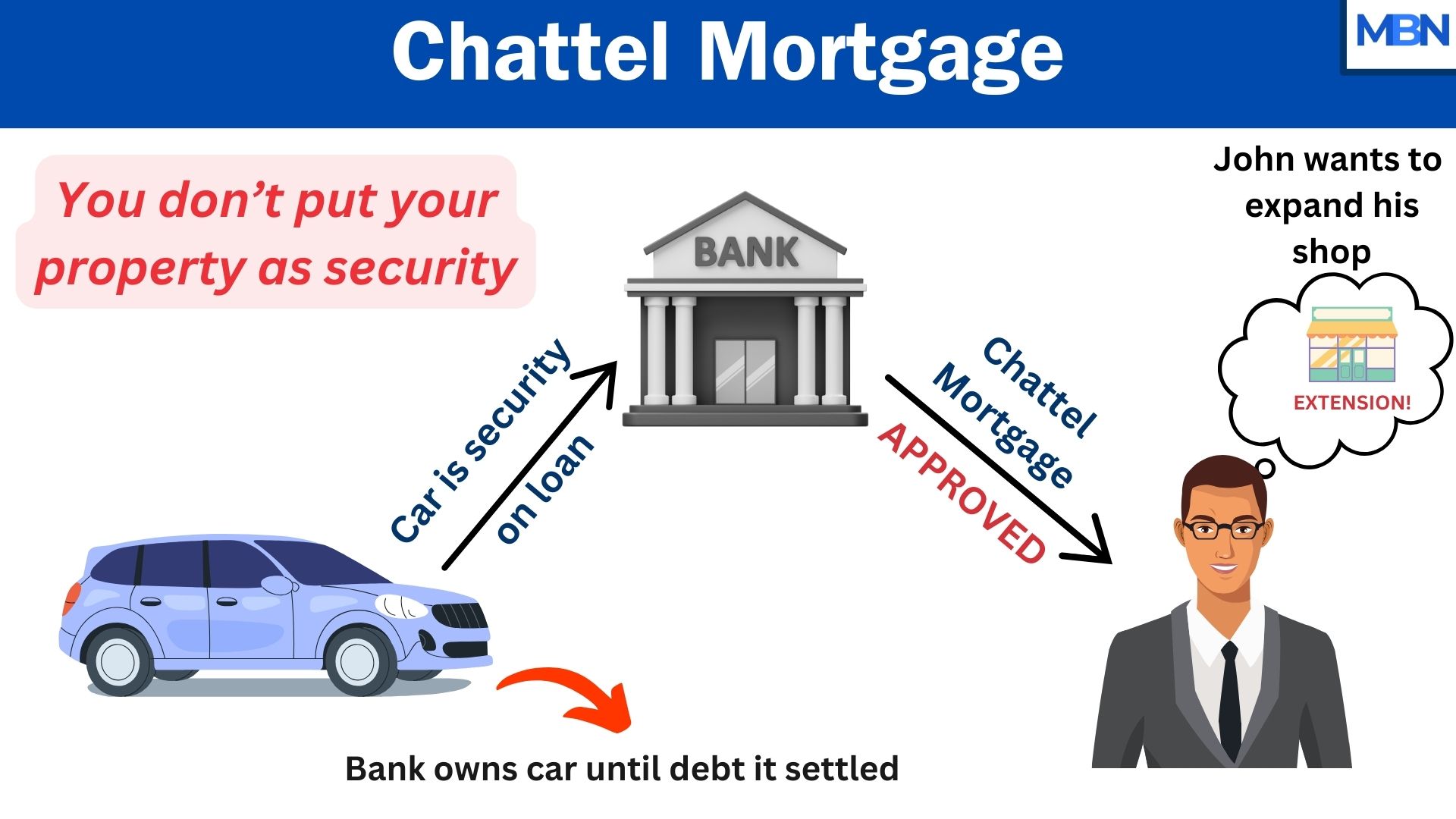

A chattel mortgage is a type of loan that is secured by a movable piece of personal property. With a chattel mortgage, you borrow money to buy something that isn’t fixed to land (for example, a car or a piece of equipment), and that item itself is used as collateral (security) for the loan.

This is similar to a regular home mortgage, but instead of a house or real estate, the loan is tied to a chattel, which means a movable item. The borrower gets the item and can use it, but the lender has a legal claim on it until the loan is repaid. Once you finish paying off the loan, the lender’s claim is removed and the item is completely yours.

Chattel is an item of property other than freehold land. The word originally comes from an old word for cattle, which were considered movable property in historical times.

If you require leverage for a loan, there are other options apart from using your house – you do not have to put your home on the line. You can use free standing possessions as security. That is where a chattel mortgage is a useful option.

Popular in Australia

Australia makes extensive use of chattel mortgages, especially for business financing. In Australia, a chattel mortgage is a common way for businesses (companies, partnerships, sole traders) to finance the purchase of vehicles or equipment that are used for business purposes.

For example, if an Australian small business wants to buy a delivery van or a piece of machinery, they might take out a chattel mortgage. The business immediately takes ownership of the vehicle (the van is registered in the business’s name), and the lender’s interest is registered on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR) – an official registry of security interests in personal property, similar in concept to the UCC filings in the U.S.

One reason chattel mortgages are popular for business in Australia is tax treatment. Under Australian tax rules, if the business accounts for GST (Goods and Services Tax) on a cash basis, it can claim the full GST paid on the purchase upfront on its next Business Activity Statement. This can help with cash flow, effectively giving a GST credit. The business can also often deduct the interest paid on the chattel mortgage and claim depreciation on the asset, as it both owns the asset and is merely using it as loan security. In essence, it’s very similar to how a business might finance a company car or equipment through a secured loan in other countries, but the term “chattel mortgage” is specifically used in Australia to describe this product.

Another point in Australia is that stamp duty (a kind of tax on loan documents) may apply to chattel mortgage arrangements in some states, which is a consideration for the cost of financing. Despite any fees, chattel mortgages are favored by many Australian businesses over leasing, because with a chattel mortgage the business owns the asset from day one, which can be beneficial if the asset’s value is likely to be higher than the loan balance as time goes on.

For Australian consumers, the term chattel mortgage isn’t as commonly applied to personal purchases (they might simply say “car loan”), but any secured loan for personal property follows the same principles. Australia’s laws ensure that lenders register their security interests and that borrowers are protected similarly to other developed countries in case of default.

Usage in other countries

In the United States, the term is not used as commonly in everyday language today, but the concept definitely is. U.S. law treats this kind of arrangement under the broad category of secured transactions.

In the United Kingdom, chattel mortgages exist but are less common in consumer finance today. UK law historically allowed individuals to use personal goods as security through documents called Bills of Sale.

In fact, England has some very old statutes – the Bills of Sale Acts of 1878 and 1882 – that lay down the format and rules for a valid chattel mortgage by individuals. Under these laws, an individual could transfer title of personal goods to a lender as security and get it back upon repayment (this is essentially a chattel mortgage). However, these arrangements have had a mixed reputation in the UK, sometimes being associated with “loan sharks” and high-rate lending in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The lender holds a lien against the chattel until the debt is paid off in full. In fact, the borrower only assumes ownership after the final loan repayment. Chattel in this context means movable property.

For something to be chattel, it must not cause any damage or change to a freehold real estate property. In other words, it must not change or damage the borrower’s building or land.

Businesses often use chattel mortgages when they need money. Companies use chattel mortgages to buy additional property. In such cases, they use their machinery and vehicles as collateral.

Examples

Car

Imagine you finance the purchase of a car using a chattel mortgage. You borrow money from the bank to buy the car, and the car is registered in your name. However, the bank is listed as a lienholder on the car’s title. You drive the car and are responsible for insurance and maintenance, just like any owner.

You make monthly loan payments to the bank. After, say, five years when you’ve made all payments, the bank’s lien is removed and the car is truly all yours. But if you had stopped making payments halfway, the bank could reclaim the car, sell it, and use the money to cover the remaining loan balance. This way, the bank is protected against the loss because the car’s value helps cover the debt.

Mobile home

Another common example is financing a mobile home (manufactured home). If the home is in a mobile home park or on someone else’s land (so the buyer owns the home but not the land underneath), a regular real estate mortgage isn’t viable because the home is considered personal property, not real property. Instead, the buyer might use a chattel mortgage. The loan is secured by the home itself as collateral.

The buyer lives in the home and pays off the loan over time. The lender holds a security interest in the structure. If the owner decides to move the mobile home to a new location, the loan can move with it because it’s tied to the home, not the land. Once the loan is fully paid, the owner owns the home free and clear. If the borrower defaults, the lender can seize the mobile home, just as with a vehicle, to recover the debt.

Business equipment

Chattel mortgages can also be used for business equipment. For example, if a company finances a piece of heavy machinery or farm equipment, the equipment acts as the chattel. The company gets the machine and uses it for its operations, but the seller or lender retains a security interest.

If the company fails to pay according to the agreement, the lender can reclaim the equipment. This arrangement allows the business to put the equipment to work and generate income while paying for it over time, but ensures the lender can get the equipment (or its value) back if the business doesn’t pay.

Chattel mortgages convenient for lenders

Lenders like chattel mortgages because if the borrower defaults they can seize the movable security. They subsequently sell that movable security. Lenders know they can sell it rapidly.

Be careful what you put up as security. You should choose a movable possession that you do not need urgently. For example, a laptop with personal files is not a good idea.

A chattel mortgage is essentially a secured loan on a movable item. The term “chattel” just means personal property, and “mortgage” in this context means the property is tied to the loan as security. By understanding chattel mortgages, you understand how consumer and business finance works: you get something now, you promise to pay over time, and the lender’s interests are protected by the ability to take back the item if you don’t pay. This system has evolved over centuries, and while laws and names differ across the world, the basic idea is common.