What is the discount rate? Definition and meaning

The discount rate can mean: 1. The interest rate that the central bank charges on money it lends to commercial banks. The US Federal Reserve, for example, does it through its discount window loan process. 2. A reduction of an invoice total if the purchaser pays before a specific date. In this sense, it also means the reduction in price per item if you buy more than a certain number. 3. The interest rate we use in discounted cash flow analysis to determine the current value of future cash flows. 4. The rate at which you can cash in an accounts receivable or bill of exchange before its maturity date.

The term may also apply to the fees that merchants have to pay when their customers use credit cards.

The bank rate, base rate, and federal discount rate all have the same or very similar meanings to the discount rate.

The word ‘discount,’ on its own, has many possible meanings.

Federal Reserve System discount rate

The discount window allows financial institutions to borrow money for short-term – 24 hours or less – operating needs.

Each of the Federal Reserve banks determine the interest rate. The Federal Reserve System’s Board of Governors reviews and also determines this.

The discount rate is generally the same across all the twelve Federal Reserve Banks, except when the discount rate changes.

Twelve Federal Reserve banks

The twelve Federal Reserve banks are: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Three loan programs

The discount window offers three loan programs, each one with its own discount rate:

– Primary Credit: the Feds main lending program for eligible financial institutions in ‘generally sound financial condition’.

– Secondary Credit: specifically for financial institutions that are not eligible for the primary program, but still need very short-term loans. They need the loans to resolve severe financial difficulty or fund short-term requirements. These loans carry a slightly higher discount rate.

– Seasonal Credit: for smaller financial institutions that have recurring cash flow fluctuations.

According to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in the United States:

“The discount rate is the interest rate charged to commercial banks and other depository institutions on loans they receive from their regional Federal Reserve Bank’s lending facility–the discount window.”

Discounted cash flow analysis

The discount rate in discounted cash flow analysis (DCF) takes into account the time value of money. It also takes into account the risk or uncertainty of future cash flows plus the effects of inflation.

The discount rate rises according to the level of uncertainty of future cash flow. It is an equation that tells us how much a series of future cash flows is worth. Specifically, how much it is worth as a single lump sum value now.

This calculation is useful for investors who wish to value investments with predictable cash flow and profits. They also use the calculation to value businesses.

DFC analysis – example

Imagine John Doe Inc., a fictitious company. It is a large blue-chip company that is over 100 years old. It it has considerable and consistent market share.

While John Doe is consistently profitable, it does not have the opportunity of faster growth. This stable, consistent and predictable company is a prime candidate for a DCF analysis.

If we can predict its future earnings, we can use DFC to determine what its valuation should be today. There is more to it than just adding up the cash flow figures and coming to a value. This is where the discount rate comes onto the scene.

Cash flow tomorrow and today

Cash flow tomorrow is worth less than cash flow today. This is mainly because of inflation and unexpected events. No future projection is 100% accurate – simply, because we just don’t know what will happen. This includes a surprise decline in John Doe’s earnings.

Cash flow today, on the other hand, is what it is – it has no such uncertainty. We must discount future cash flow, given that any future forecast carries a risk, to compensate for the risk we take in waiting for it to come.

These two factors – the uncertainty risk and money’s time value – together form the theoretical basis for the discount rate. The greater the uncertainty the higher the discount rate, and the lower the current value of our future cash flow.

According to ft.com/lexicon, the discount rate is:

“The interest rate charged by a central bank to commercial banks when lending short-term funds (by discounting government paper or using government paper as collateral). In the US, the discount rate, which acts as a reference rate for commercial banks’ own lending rates, is one of the two key rates manipulated by the Federal Reserve to control money supply (the other being the Federal funds rate).”

“The discount rate is also the interest rate at which commercial banks discount bills of exchange. The term also refers to the interest rate used to calculate discounted cash flow.”

Discounted bill of exchange

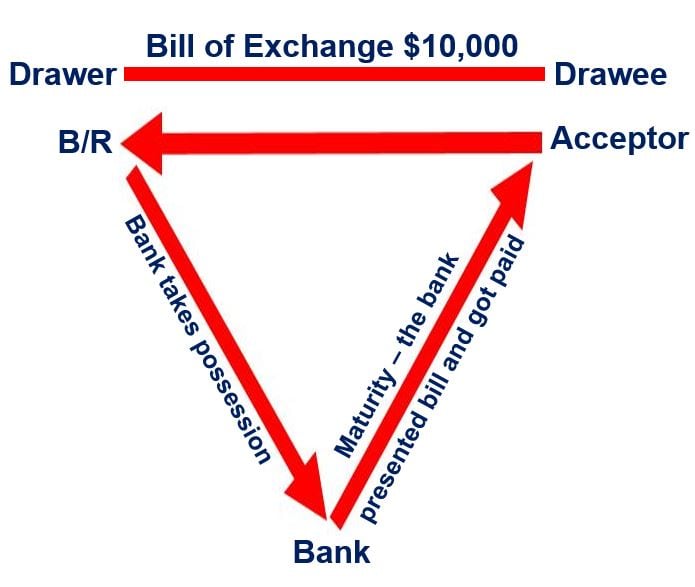

Discount may also refer to an accepted draft or bill of exchange that is sold to a bank or credit institution for early payment at less than face value after the bank deducts applicable interest charges and fees.

The bank then collects the bill of exchange’s or draft’s full value when payment comes due.

For example, imagine you have a bill for $10,000. You discount this bill with your bank two months before its due date at 15% p.a. rate of discount. We calculate the discount as follows:

1,000 × 15/100 × 2/12 = 250

So, you will receive $9,750 in cash and bear a loss of $250. The bank will hold onto this bill until the due date and present it to the acceptor. The acceptor – if the bill is honored – will pay the $10,000 to the bank.

If the bill is not honored, you will be liable, i.e. you will have to pay the cash to the bank.