Golden handshake – definition and meaning

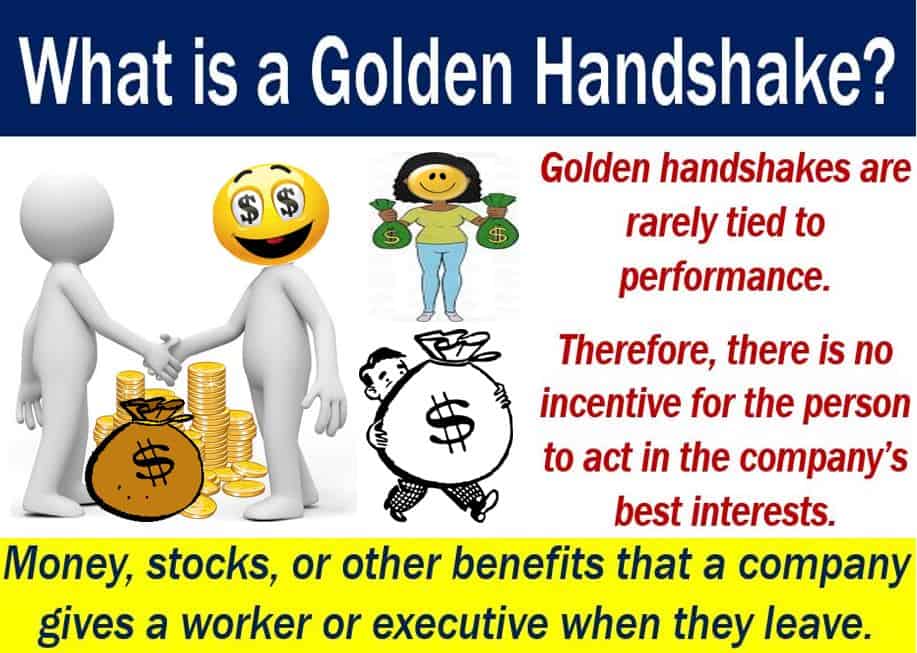

A golden handshake is money, often a large sum, that an employer gives an employee when they leave. The money is a reward for good work or many years of service. It is a bonus that the partners, directors, or employees get as a severance payment. Companies sometimes offer a golden handshake to encourage people to leave. The inducement may exist to prevent the employee from creating a controversy or making a fuss.

In other words, a golden handshake may be either ‘thank you’ money or a financial incentive to leave quietly.

Often, especially with directors, golden handshakes form part of their employment agreement. The agreement, for example, may state that the company will provide a generous severance package if the director must leave.

According to Merriam-Webster, a golden handshake is:

“A large amount of money that a company gives to an employee who is leaving the company.”

Frederick Ellis, City Editor of the Daily Express, a British tabloid, coined the term in the mid-1960s.

Golden handshake – many sizes

Golden handshakes can vary in size from a few hundred to several million dollars. For a long-serving factory worker, for example, it may consist of one week or month for each year of service.

However, for top executives, especially CEOs of giant multinationals, the amount could be hundreds of millions of dollars.

Frederick Ross Johnson, for example, received $53 million in 1989 when he left as CEO of RJR Nabisco.

In 2006, William McGuire received a golden handshake from UnitedHealth Group Inc. worth $1.6 billion in stock. During his fifteen years as CEO, the company’s revenue rose from $400 million to $70 billion.

Top executives argue that they deserve golden handshakes because of the inherent nature of their jobs. Put simply; they say they are much more likely to lose their jobs than other employees.

Some people wonder how many executives have deliberately tried to get fired. If their employment contract has a very generous golden handshake clause, mightn’t they try to organize their own dismissal?

Shareholder rebellions

Since the 2007 global financial crisis, shareholder rebellions have become more common. Investors get extremely angry when top executives of failing companies get a sendoff worth tens of millions of dollars.

In many cases, shareholders have initiated lawsuits and managed to recover some of the money. In other words, the shareholders sued.

The term ‘shareholder rebellion’ refers to irate stockholders who get together and challenge decisions that directors of a company made.

Shareholders are usually happy to reward a CEO who has increased dividend payments and reported healthy profits. However, they are not so keen when there have been no dividends or the company is failing.

Golden handshake and company’s public image

Golden handshakes have always been controversial. Typically, those who receive them argue that they are necessary, while most other people in the company disagree.

However, when a company is struggling, a large golden handshake can seriously damage its public image.

In 2010, BP, a British multinational oil giant, had a disastrous oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. We refer to it as the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Eleven people died in the explosion. It was the largest marine oil spill in petroleum industry history.

During the spill, approximately 4.9 million barrels of petroleum was discharged. The spill devastated local wildlife, beaches, and ruined many businesses.

BP had to pay out more than $60 billion following the accident. Not long after having to pay out the money, Tony Hayward, BP’s CEO, was pushed out.

However, Hayward received a golden handshake of $1.61 million plus a $17 million pension fund. The payout damaged BP’s public image considerably. It also confirmed many people’s suspicion that the fat-cat environment of big business had survived the 2007 global financial crisis.