What is the national debt? Definition and meaning

National debt is the total amount of money that the government owes, including what it borrowed from national creditors – internal debt – and foreign creditors – external or foreign debt. The money borrowed is used to finance public expenditure. The national debt also includes how much local government has borrowed.

It is all the money the government has ever borrowed and still owes, which is not the same as the annual public-sector budget deficit, which is the difference between how much a government receives in taxes and how much it spends in a single year. A government may have a massive budget surplus one year, but still have a sizable national debt.

The national debt, also known as the government debt, public interest or sovereign debt, is frequently described as a burden, even though the money borrowed typically has economic benefits.

Governments that become heavily in debt are said to be creating a burden for future generations, especially if the funds are mismanaged or invested unwisely.

According to lexicon.ft.com, the Financial Times’ glossary of business and economic terms, to define national debt is as follows:

“What a government borrows to ensure it can finance all its planned expenditure (and plug its budget deficit). If a government is running a budget surplus, it should not in principle need to increase its debt. A government will normally borrow money by issuing bonds or other securities. Local governments, specific departments or agencies may issue their own bonds to finance expenditure.”

“Rather than issuing paper, the government of a developing country with low credit ratings may need to negotiate loans from foreign governments, institutions such as the World Bank or overseas bank creditors.”

The US National Debt

Near Times Square in New York, there is an electronic billboard that tracks the US national debt. When it was first installed – 1989 – the national debt stood at about $3 trillion (twelve zeros). Since then, the US federal debt has soared to over $30 trillion.

How national debt is created

Governments, states, municipalities (UK: town or country councils), and other local authorities usually raise money by issuing government bills, government bonds, and securities.

Some emerging nations with low credit ratings may borrow from the World Bank, or another international organization.

Government bonds are bonds issued by a national government. They are usually denominated in the nation’s domestic currency.

Sometimes, the money is raised in a foreign currency, such as the US dollar. In the year 2000, seventy percent of all public debt was denominated in US dollars.

Government bonds are typically regarded as risk-free bonds, because the national government can, if it has to, create de novo to redeem the bond in its own currency at maturity.

In all the advanced economies and many emerging nations, governments are not allowed to create money directly – this is the central bank’s function. However, central banks may provide funds by purchasing government bonds, i.e. they monetize the debt.

If a government issues government bonds denominated in a foreign currency, there is a risk that the debt may increase dramatically if the domestic currency devalues. Additionally, if obtaining that foreign currency to service the debt is difficult, there could be serious problems.

Munis are municipal bonds in the United States; debt securities issued by municipalities (local governments).

National debt-to-GDP ratio

The national debt-to-GDP ratio is the ratio of the national debt and the country’s GDP (gross domestic product). A low debt-to-GDP ratio shows that the country produces and sells products and services in sufficient quantities to pay back and service debts without further borrowing.

Often, economists and newspapers use the term government debt-to-GDP, which is expressed as a percentage. For example, if a country’s national debt is $110 billion and its GDP is $100 billion, its government debt-to-GDP is 110%.

According to TradingEconomics.com, in 2015, the United States recorded a government debt-to-GDP ratio of 104.17%. From 1940 to 2015, the country’s government debt-to-GDP averaged 61.94%. In 1946, it reached an all-time-high of 121.70%, while in 1974 it registered its lowest debt burden – 31.70%.

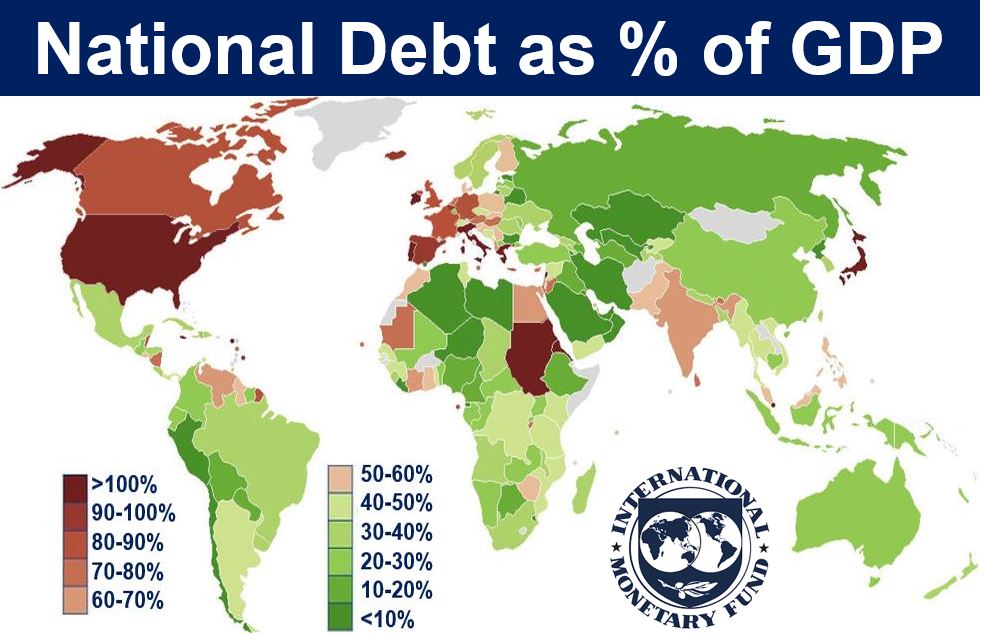

With the exception of Australia and New Zealand, national debt as a percentage of GDP is considerably higher in the advanced economies than in the emerging ones. (Image: Adapted from Wikipedia)

With the exception of Australia and New Zealand, national debt as a percentage of GDP is considerably higher in the advanced economies than in the emerging ones. (Image: Adapted from Wikipedia)

Is the national debt risk-free?

Lending to a national government in that country’s domestic currency is usually considered ‘risk-free’. This is because the interest and debt – the national debt – can be paid back by raising tax receipts, cutting spending, or printing new money.

If the government decides the create more money, the inflation rate will rise, which will reduce the real value of the government bonds.

In Weimer Germany (Weimar Republic) in the 1920s, when hyperinflation meant prices rose by several thousand percent each year, the government massively printed money to cover its debts and public expenditure. The real value of its bonds declined considerably.

The interest rate paid on government bonds varies, depending on how stable and solvent a country’s economy is estimated to be. For example, in the eurozone – countries that use the euro as their national currency – interest rates on Greek bonds are higher than those issued in Germany. The more solvent an economy is, the lower the interest rates on its bonds are.

Government bonds issued in the United States, Germany, United Kingdom, Japan and Switzerland, for example, are considered as risk-free as you can get, because those countries historically have had excellent credit ratings, and stable economies. It is cheaper for the United States to service its national debt (proportionally) than it is for Venezuela, because interest rates in the US are considerably lower.

Even so, the sovereign ratings of the UK, France and the USA since the global financial recession of 2007/8 have slipped.

Other languages

Below you can see a translation of the term ‘The National Debt’ in various different languages:

- Spanish: La deuda nacional

- Hindi: राष्ट्रीय ऋण

- French: La dette nationale

- Arabic: الدين العام

- Bengali: জাতীয় ঋণ

- Russian: Государственный долг

- Portuguese: A dívida nacional

- Indonesian: Utang Nasional

- Urdu: قومی قرض

- German: Die Staatsschulden

- Japanese: 国の借金

- Swahili: Deni la Taifa

- Marathi: राष्ट्रीय कर्ज

- Telugu: జాతీయ ఋణం

- Turkish: Ulusal Borç

- Korean: 국가 부채

- Tamil: தேசிய கடன்

- Vietnamese: Nợ quốc gia

- Italian: Il debito pubblico

- Gujarati: રાષ્ટ્રીય દેવું

- Farsi: بدهی ملی

- Bhojpuri: राष्ट्रीय कर्जा

- Hakka: 國家債務 (This term may vary regionally, and Hakka speakers might use the standard Mandarin term.)

- Mandarin Chinese: 国家债务

- Cantonese Chinese: 國家債務

- Jin Chinese: 國家債務 (This term may vary regionally, and Jin Chinese speakers might use the standard Mandarin term.)

- Southern Min: 國家債務 (This term may also be based on the Mandarin term, as specific Southern Min terms can vary.)

- Kannada: ರಾಷ್ಟ್ರೀಯ ಸಾಲ

Video – What is The National Debt?

This video, from our sister channel in YouTube – Marketing Business Network, explains what ‘The National Debt’ is, using simple and easy-to-understand language and examples.