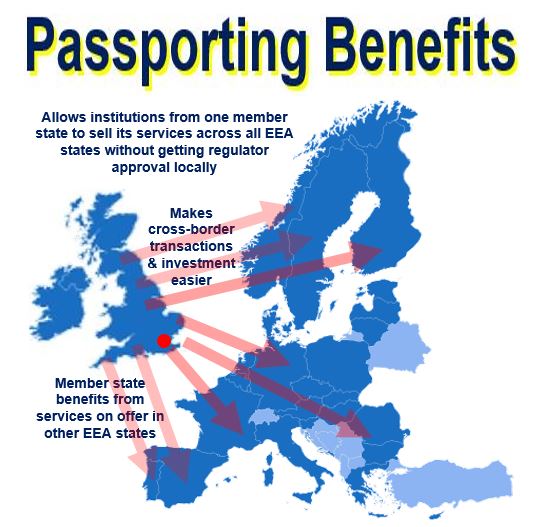

Passporting or passporting rights refers to exercising the right for a company registered in the EEA (European Economic Area) to do business in any other EEA country without having to request further authorization in that country. Put simply, it is a type of passport that financial institutions get to do business across the whole of Europe.

The EEA agreement, which was established in 1991, is an area in Europe which provides for the free movement of goods, services, capital and people. There are thirty-one EEA member states – 28 European Union member states plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway.

The following EEA countries currently have passporting rights: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus (southern part), Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

The main benefit of passporting is being able to operate across a whole continent without having to apply to each country’s regulatory authorities individually.

The main benefit of passporting is being able to operate across a whole continent without having to apply to each country’s regulatory authorities individually.

Non-EEA companies, such as those based in the US or Japanese will get authorized by one EEA state – if they set up an office there – and use that country’s passporting rights to either provide cross-border services or open an establishment elsewhere in the EEA.

When an EEA state plans to undertake cross-border services, it must apply for a passport. In the UK, for example, the Bank of England says this is done with the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA).

You may need a different passport to be able to offer advice on different products – even if you are advising just one client on a range of products.

As long as you meet the conditions set out in the relevant directive, you can either:

– get a Services Passport, which allows you to provide cross-border services, or

– get an Establishment or Branch Passport: which allows you to set up a branch in an EEA state.

Switzerland is not an EEA state. However, Swiss general insurers are allowed to set up an establishment in the EEA under special bilateral treaties between Switzerland and the EU. EEA general insurers can also set up an establishment in Switzerland.

Head of the German Federal Bank Jens Weidmann (top left) said a hard Brexit would definitely mean the loss of passporting rights. Credit agency Moody’s (bottom left), however, does not believe losing passporting would be that bad for the City of London.

Head of the German Federal Bank Jens Weidmann (top left) said a hard Brexit would definitely mean the loss of passporting rights. Credit agency Moody’s (bottom left), however, does not believe losing passporting would be that bad for the City of London.

Passporting does away with having to go through all the red tape associated with getting authorization from each country individually, a process that is expensive and time-consuming for companies.

Regarding passporting, the European Banking Authority writes:

“In accordance with the principle of single authorization, the decision to issue an authorization valid for the entire EU shall be the sole responsibility of the competent authorities of the home Member State.”

“A financial institution may then provide the services, or perform the activities, for which it has been authorised, throughout the Single Market, either through the establishment of a branch or the free provision of services.”

Does Brexit mean no more passporting?

The big question now – after Britons voted on June 23rd to leave the European Union – is whether the UK will lose its passporting rights after Brexit occurs. London, Europe’s major financial center, is an important hub for non-EEA-based companies that do business within the EU.

Brexit stands for Britain Exiting the EU.

After the Brexit vote, financial markets experienced a high level of uncertainty because nobody knew what would happen to the British economy. Would most of the non-EEA companies that use London as their European headquarters leave the city and move their operations across the channel in order to retain their passporting rights and access to the single market?

Not only non-European companies are worried, but British ones too. Currently, UK companies can provide a range of financial services anywhere in the EU and the wider EEA. Will they also have to move some of their operations into the European mainland if those passporting rights are lost?

The longer this uncertainty lingers the more nervous London-based financial services companies will become. Earlier this month, Lloyd’s of London said it may have to move some of its operations to continental Europe.

The financial services sector accounts for 3.4% of all jobs in the UK, 8% of its GDP (gross domestic product) and 10% of its exports. Any deterioration in this sector’s ability to do business would have a considerable impact on Britain’s overall economy.

British Foreign Secretary, Boris Johnson, who campaigned for Brexit prior to June’s referendum, believes that London will keep its passporting rights. Mr. Johnson said: “In the European time zone, London is the place to do it (financial business). That will continue.” (Image: Wikipedia)

British Foreign Secretary, Boris Johnson, who campaigned for Brexit prior to June’s referendum, believes that London will keep its passporting rights. Mr. Johnson said: “In the European time zone, London is the place to do it (financial business). That will continue.” (Image: Wikipedia)

Passporting post Brexit

What will happen to passporting rights after Brexit occurs and what impact will that have on Britain’s financial services?

That depends on what type of Brexit there will be – a hard one or a soft one.

– Hard Brexit means there is no trade deal between the UK and EU, and passporting rights are lost.

– Soft Brexit means some of the privileges enjoyed by EU member states, such as free access to the single market and passporting will prevail.

If Britain remains in or re-joins the EEA, companies in London will be able to carry on operating across the EEA countries as they currently do.

If the UK left the EU without retaining EEA membership, the country would have two options regarding passporting:

1. Some level of bilateral agreements, as there currently is with Switzerland.

2. No passporting agreement at all.

Both these options would have a detrimental impact on the ability of British companies to provide comprehensive services to the rest of the EEA.

London’s status as Europe’s major financial center, its influence in helping to set financial regulations across the world, plus its current compliance with EU directives on financial services, makes it extremely likely that the European Union will want to come to a passporting agreement so that its businesses can retain access to Britain’s financial services.

However, many experts argue that some EU cities such as Frankfurt and Paris would be happy grab London’s current status as Europe’s leading financial hub, and will push for Britain to be denied any passporting rights.

Passporting – German Federal Bank comment

Jens Weidmann, head of the German Federal Bank, said in September 2016 that UK banks would lose valuable passporting rights if the UK finally left the EU completely, i.e. if there was a hard Brexit.

Mr. Weidmann said that passporting rights are “tied to the single market and would automatically cease to apply if Great Britain is no longer at least part of the European Economic Area.”

If the UK loses its passporting rights, Mr. Weidmann expects ‘several businesses’ will reconsider using London as their European headquarters.

Mr. Weidmann added:

“As a significant financial centre and the seat of important regulatory and supervisory bodies, Frankfurt is attractive and will welcome newcomers. But I don’t expect a mass exodus from London to Frankfurt.”

Moody’s says passporting loss would be manageable

Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s), the bond credit rating business of Moody’s Corporation, one of the world’s most respected credit agencies, said in a report that the loss of passporting rights would have a modest and manageable effect on the City (London’s financial district).

According to Moody’s:

“The greater impact would be felt through higher costs and diversion of management attention, as the companies concerned restructure, reducing profitability for a time.”

“This is credit negative but manageable. And other critical factors such as capital and liquidity, which are largely determined by global standards, are unlikely to face material changes due to Brexit per se.”

According to Simon Ainsworth, Senior Vice-President at Moody’s, incoming financial services regulations could provide alternative means of accessing the single market.

Mr. Ainsworth said:

“In particular, we consider that the third-country equivalence provisions contained within the incoming MiFID II EU directive may provide firms with an alternative means of accessing the single market.”

“The complexity of (quickly) unwinding the status quo and a desire to minimise the initial impact on European domiciled banks will likely lead to the preservation of most cross-border rights to undertake business.”

Video – Passporting after Brexit

Jon Danielsson, a Reader in Finance at the London School of Economics, talks about what the UK faces in the future if it loses or retains its passporting rights.