A posteriori – definition and meaning

A posteriori is a judgment or conclusion based on experience or by what others tell us about their experiences. For example, I know the Sun will set this evening because it always has. My a posteriori knowledge tells me that the sun will set again. The Sun setting is a conclusion I have from something I have experienced all my life.

I also know that millions of people in Tokyo will speak Japanese tomorrow. I have never been to Tokyo; it is not my experience. However, I know this from other people’s testimony. I have gained with knowledge by watching TV, listening to the radio, reading newspapers, and listening to other people.

Hence, my a posteriori knowledge tells me that the Sun will rise and that many Tokyo residents speak Japanese.

A priori vs. a posteriori

The term a posteriori contrasts with a priori. We gain a priori knowledge through pure reasoning. A priori comes from our intuition or innate ideas.

For example, I know that 2+2=4 because of pure reasoning; in other words, a priori knowledge. The sum does not happen because I have seen it happen, so I assume it will happen again.

The sum, 2+2=4, happens because I worked out the numbers in my head. I came to that conclusion because of logic rather than making a prediction due to experience.

According to Dictionary.com, a posteriori is:

“1. From particular instances to a general principle or law; based upon actual observation or upon experimental data: ‘An a posteriori argument that derives the theory from the evidence’. 2. Not existing in the mind prior to or independent of experience.

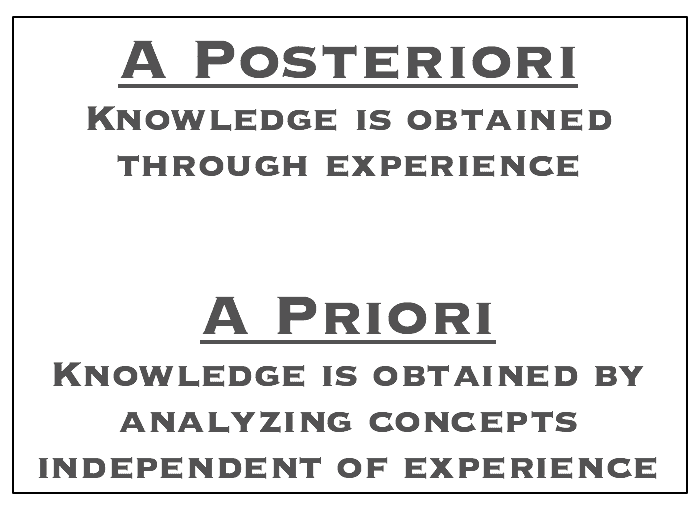

‘A posteriori’ refers to knowledge that we obtain through experience. It also refers to knowledge we acquire from other people’s testimony, i.e. listening to others’ experiences. ‘A priori’ is knowledge we obtain by analyzing concepts and using logic. In other words, ‘a priori’ is independent of experience.

‘A posteriori’ refers to knowledge that we obtain through experience. It also refers to knowledge we acquire from other people’s testimony, i.e. listening to others’ experiences. ‘A priori’ is knowledge we obtain by analyzing concepts and using logic. In other words, ‘a priori’ is independent of experience.

The University of Tennessee Martin’s Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy makes the following comment regarding the two Latin terms:

“In general terms, a proposition is knowable a priori if it is knowable independently of experience, while a proposition knowable a posteriori is knowable on the basis of experience.”

“The distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge thus broadly corresponds to the distinction between empirical and non-empirical knowledge.”

A posteriori – empirical

We also call a posteriori knowledge empirical knowledge. With empirical thinking, we base our knowledge on experience or observation, rather than theory or pure logic.

We consider the natural sciences as a posteriori disciplines. The social sciences are also a posteriori disciplines. Social sciences include economics, politics, human geography, demography, sociology, anthropology, jurisprudence, history, and linguistics. Jurisprudence is the study of law.

Logic and mathematics, on the other hand, are a priori disciplines.

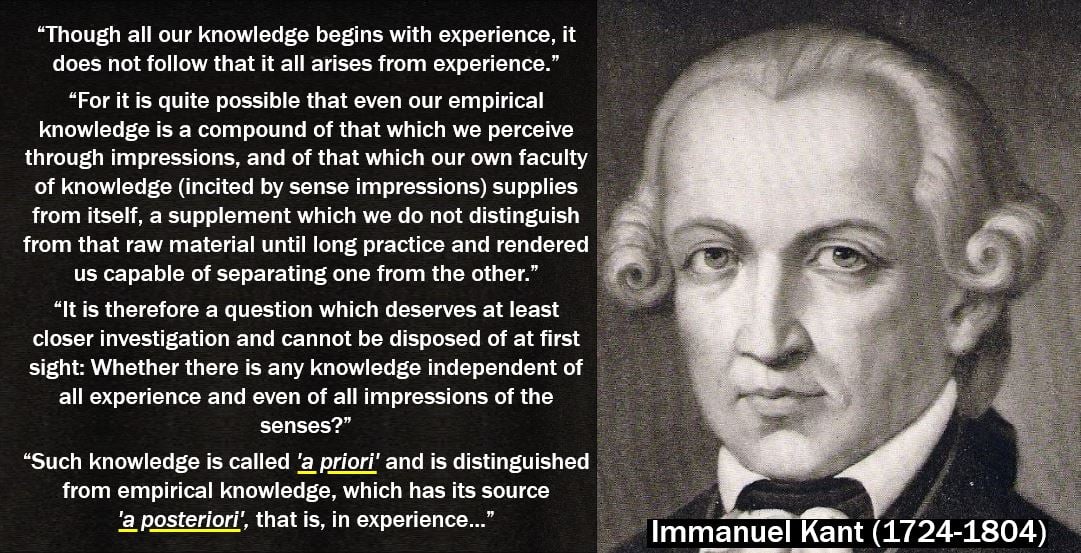

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), born in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), was probably the most influential thinker of the Enlightenment era. In fact, today we see him as one of the leading Western philosophers of all times. His works had a profound influence on later and contemporary philosophers. His works in the theory of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and aesthetics especially, influenced philosophers. (Image: adapted from philosophers.co.uk)

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), born in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), was probably the most influential thinker of the Enlightenment era. In fact, today we see him as one of the leading Western philosophers of all times. His works had a profound influence on later and contemporary philosophers. His works in the theory of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and aesthetics especially, influenced philosophers. (Image: adapted from philosophers.co.uk)

A posteriori is a Latin term which translates into English as ‘from the one behind.’ A priori is also a Latin, and means ‘from the one before.’

We gain most of our empirical knowledge through a combination of direct experience and what other people tell us.

Scientists use more complicated and organized ways of gaining empirical knowledge.

The statement ‘God exists’

Is the statement ‘God exists’ the result of empirical knowledge or pure logic? Most philosophers will say that it is a trick question because we can argue the answer either way.

If we propose that ‘God exists’ from design in the world, we are presenting an empirical argument. I have to experience ‘design’ to present the argument of God as the grand designer. Therefore, the argument is empirical, says one argument.

By arguing that ‘God exists‘ because it makes logical sense, then I am presenting an a priori analytical argument. “This is because, according to Anselm, existence is a logical necessity for God,” says an article in Philosophyzer.wordpress.com.

Video – A priory/posteriori

This Philosophy Tube video explains what ‘a priori’ and ‘a posteriori’ mean. We gain a priori knowledge by analyzing concepts independent of experience. On the other hand, we gain a posteriori knowledge through experience. They are both methods of obtaining knowledge.