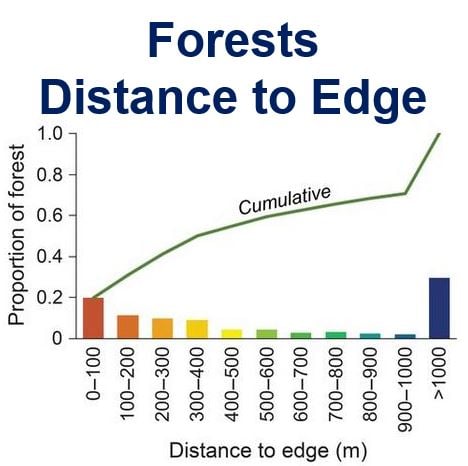

Forests globally are shrinking at an alarming rate. Today, seventy percent of forest lands are within half-a-mile (1 km) of the forest edge, where agricultural and suburban influences, plus urban encroachment can undermine the survival of animals and plants, an international research team led by North Carolina State University reported.

In other words, most of the world’s forests are very small, where it is impossible for a really wide variety of plants and animals to thrive.

The scientists tracked seven major experiments that took place on five continents that examined habitat fragmentation. They found that fragmented habitats reduced the diversity of animals and plants by between 13% and 75%, with the worst affected habitats being the smallest and most isolated fragments.

The study findings have been published by the academic journal Science Advances (citation below).

After creating a map of global forest cover, the scientists found there are very few forests left that are unencumbered by some type of human development.

Virtually no wilderness-type forests left

Corresponding author, Dr. Nick Haddad, William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor of Biological Sciences at NC State, said:

“It’s no secret that the world’s forests are shrinking, so this study asked about the effects of this habitat loss and fragmentation on the remaining forests.”

“The results were astounding. Nearly 20 percent of the world’s remaining forest is the distance of a football field – or about 100 meters – away from a forest edge. Seventy percent of forest lands are within a half-mile of a forest edge. That means almost no forest can really be considered wilderness.”

Dr. Haddad and colleagues also gathered and analyzed data from seven existing major experiments on fragmented habitats that are currently being conducted in various parts of the world. Some of them started more than thirty years ago.

The experiments, which cover several types of ecosystems, including grasslands, forests and savannas, paint a depressing picture. They show that fragmentation causes the loss of animals and plants, alters how ecosystems function, reduces the amounts of nutrients retained, lowers the amount of carbon absorbed from the atmosphere, plus a number of other harmful effects.

Dr. Haddad said:

“The initial negative effects were unsurprising. But I was blown away by the fact that these negative effects became even more negative with time. Some results showed a 50 percent or higher decline in plant and animals species over an average of just 20 years, for example. And the trajectory is still spiraling downward.”

Mitigating the effects of fragmentation

There are some ways the negative effects of fragmentation can be reduced, Dr. Haddad says:

- conserving and maintaining larger habitat areas,

- utilizing landscape corridors, or connected fragments that are effective in achieving higher biodiversity and better ecosystem function,

- improving agricultural efficiency,

- concentrating on urban design efficiencies.

Dr. Habbad said:

“The key results are shocking and sad. Ultimately, habitat fragmentation has harmful effects that will also hurt people. This study is a wake-up call to how much we’re affecting ecosystems – including areas we think we’re conserving.”

The study was financed by the National Science Foundation.

Citation: “Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems,” Nick M. Haddad, Lars A. Brudvig, Jean Clobert, Kendi F. Davies, Andrew Gonzalez, Robert D. Holt, Thomas E. Lovejoy, Joseph O. Sexton, Mike P. Austin, Cathy D. Collins, William M. Cook, Ellen I. Damschen, Robert M. Ewers, Bryan L. Foster, Clinton N. Jenkins, Andrew J. King, William F. Laurance, Douglas J. Levey, Chris R. Margules, Brett A. Melbourne, A. O. Nicholls, John L. Orrock, Dan-Xia Song, and John R. Townshend. Science Advances. Published 20 March, 2015. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500052.