Huge amounts of ancient carbon stored in Arctic permafrost are being transformed into carbon dioxide and released into the atmosphere because temperatures are rising, scientists reported last week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. This carbon has been locked up in the frozen region for more than 20,000 years.

While most of the world’s climatologists are concentrating on CO2 levels in the atmosphere, a group of scientists from the US, UK, Germany, Switzerland and Russia is exploring a colossal storehouse of carbon that has the potential to considerably affect the climate change picture.

Assistant Professor Aron Stubbins, a researcher at the University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, and colleagues are focusing on ancient carbon that has been locked away in Arctic permafrost for thousands of years, and is now making its way into our atmosphere as CO2.

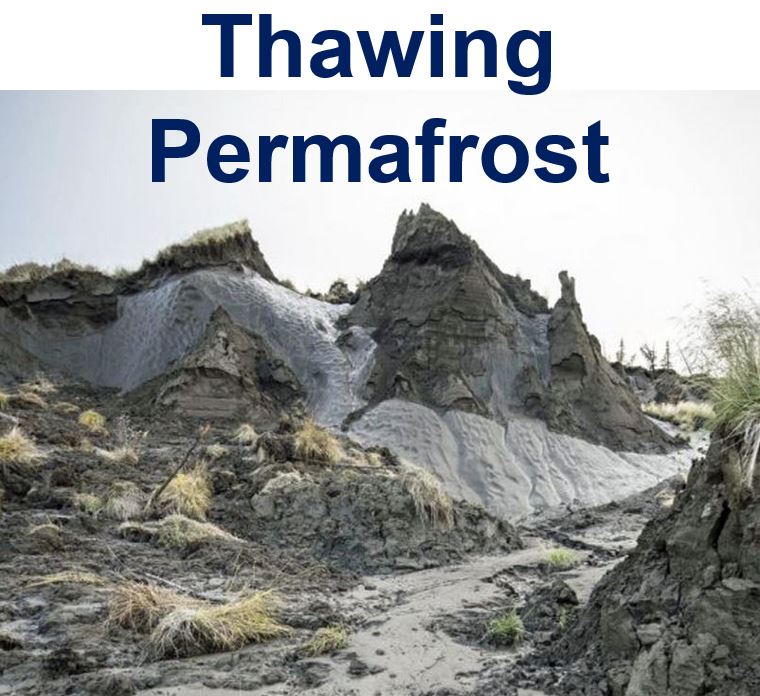

A bank of permafrost thaws near the Kolyma River in Siberia. (Image: Skidaway Institute of Oceanography)

Massive amounts of carbon in the form of frozen soil – the remnants of animals and plants that died over 20,000 years ago – are stored in the Arctic.

As this organic material has been permanently frozen all year round, it has never undergone decomposition by bacteria the way organic material does at higher temperatures.

Permafrost starting the thaw

Just like the food in your freezer at home, it has been locked away from bacteria that would otherwise cause it to decay and convert it into CO2.

Prof. Stubbins said:

“However, if you allow your food to defrost, eventually bacteria will eat away at it, causing it to decompose and release carbon dioxide. The same thing happens to permafrost when it thaws.”

It is estimated that the amount of carbon in the Arctic soil is ten times greater than all the carbon that has been put into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution started.

Looking at it another way, researchers have calculated there is 2.5 times more carbon locked away in the Arctic than there currently is in our atmosphere.

As our planet warms up, that Arctic deep freezer is starting to thaw and that long-frozen carbon is beginning to make its way into our atmosphere.

Prof. Stubbins said:

“The study we did was to look at what happens to that organic carbon when it is released. Does it get converted to carbon dioxide or is it still going to be preserved in some other form?”

In this latest study, the research team carried out its fieldwork at Duvanni Yar in Siberia, where the Kolyma River carves into a bank of permafrost, exposing the frozen organic material.

The scientists managed to find streams that consisted of 100% thawed permafrost. They measured carbon concentrations, how old the carbon was, and what forms of carbon were present in the water.

They then bottled it with a sample of local microbes, and measured the changes in the carbon concentration after two weeks, as well as its composition and amount of CO2 that had been produced.

Prof. Stubbins said:

“We found that decomposition converted 60 percent of the carbon in the thawed permafrost to carbon dioxide in two weeks. This shows the permafrost carbon is definitely in a form that can be used by the microbes.”

Lead author Robert Spencer, Assistant Professor at Florida State University added:

“Interestingly, we also found that the unique composition of thawed permafrost carbon is what makes the material so attractive to microbes.”

Their findings also confirmed what they had suspected – the carbon being used by the bacteria is at least 20,000 years old. This is significant; it means that the carbon being used is not part of the global carbon cycle in the recent past.

Prof. Stubbins explained:

“If you cut down a tree and burn it, you are simply returning the carbon in that tree to the atmosphere where the tree originally got it. However, this is carbon that has been locked away in a deep-freeze storage for a long time.”

“This is carbon that has been out of the active, natural system for tens of thousands of years. To reintroduce it into the contemporary system will have an effect.”

Carbon release will create a a positive feedback loop

This carbon release could create what the researchers call a positive feedback loop – as more carbon is released into the atmosphere, it would amplify global warming, which in turn, would result in further thawing of permafrost and the release of even more carbon, thus perpetuating the cycle.

Prof. Spencer said:

“Currently, this is not a process that shows up in future (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) climate projections; in fact, permafrost is not even accounted for.”

Prof. Stubbins added:

“Moving forward, we need to find out how consistent our findings are and to work with a broader range of scientists to better predict how fast this process will happen.”

Citation: “Detecting the Signature of Permafrost Thaw in Arctic River,” Robert G. M. Spencer, Paul J. Mann, Thorsten Dittmar, Timothy I. Eglinton, Cameron McIntyre, R. Max Holmes, Nikita Zimov and Aron Stubbins. Geophysical Research Letters. Published 23 April, 2015. DOI: 10.1002/2015GL063498.