A record number of corals have died this year in the Great Barrier Reef – 2016 has seen the largest die-off of corals since records began, say scientists from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies in Australia.

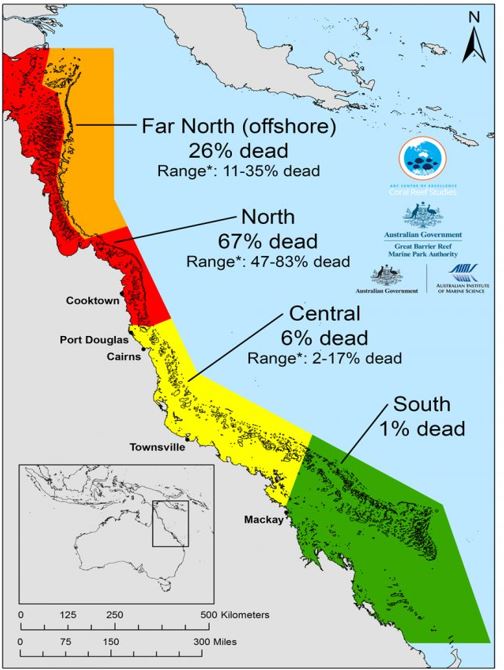

A 700-kilometer (435-mile) stretch of reefs in the northern region of Australia’s Great Barrier reef has lost an average of sixty-seven percent of its shallow-water corals since the first quarter of this year.

Scientists were relieved to discover that the vast central and southern regions fared better – even though deaths were registered, numbers were significantly lower.

Average loss of corals along each section of the Great Barrier Reef. (Image: coralcoe.org.au)

Average loss of corals along each section of the Great Barrier Reef. (Image: coralcoe.org.au)

Most corals died in northern section

Professor Terry Hughes, Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, based at James Cook University, who carried out extensive aerial surveys at the height of the bleaching, said:

“Most of the losses in 2016 have occurred in the northern, most-pristine part of the Great Barrier Reef. This region escaped with minor damage in two earlier bleaching events in 1998 and 2002, but this time around it has been badly affected.”

Andrew Baird, Professorial Research Fellow and Chief Investigator, an ARC Future Fellow at James Cook University, who re-surveyed the reefs in October and November with a team of divers, said:

“The good news is the southern two-thirds of the Reef has escaped with minor damage. On average, 6% of bleached corals died in the central region in 2016, and only 1% in the south. The corals have now regained their vibrant colour, and these reefs are in good condition.”

Research team member, Grace Frank, completing a bleaching survey in the southern Great Barrier Reef. (Image: coralcoe.org.au)

Research team member, Grace Frank, completing a bleaching survey in the southern Great Barrier Reef. (Image: coralcoe.org.au)

Tourism industry spared

People employed in the tourism industry can breathe a sigh of relief after hearing that the southern two-thirds of the Reef fared better.

Craig Stephen, who runs one of the Great Barrier Reef’s biggest live-aboard tourist operations, said: “This is welcome news for our tourism industry.”

Great Barrier Reef tourism employs over seventy-thousand people, and generates approximately $5 billion in income annually.

Mr. Stephen added:

“The patchiness of the bleaching means that we can still provide our customers with a world-class coral reef experience by taking them to reefs that are still in top condition.”

In the northern offshore corner of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, coral death figures were considerably lower than in the other northern reefs, researchers reported.

They talked to people who study, care, work and rely on it. This is how you save the #GreatBarrierReef https://t.co/zJtZH9B7YS pic.twitter.com/J6cmKOPEVU

— Greenpeace (@Greenpeace) November 28, 2016

Prof. Hughes said:

“We found a large corridor of reefs that escaped the most severe damage along the eastern edge of the continental shelf in the far north of the Great Barrier Reef.”

“We suspect these reefs are partially protected from heat stress by upwelling of cooler water from the Coral Sea.”

It will take at least a decade, and perhaps up to fifteen years, for the area to recover. Scientists are worried about what might happen if a fourth bleaching event occurs sooner and halts the slow recovery.

What is coral bleaching?

Coral bleaching occurs when unfavourable environmental conditions, such as rising sea temperatures, cause corals to expel tiny photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae.

When the corals turn white – when they bleach – they are at risk of death if water temperatures do not cool.

When the corals turn white – when they bleach – they are at risk of death if water temperatures do not cool.

When zooxanthellae levels fall below a certain point, corals bleach – they turn white. If the water temperature cools and the tiny algae can recolonise the corals, they have a chance at making a full recovery – otherwise they will probably perish.

Scientists say that the impact of coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reeeef is still unfolding.

Prof. John Pandolfi, who works at the ARC Centre at the University of Queensland, said earlier this year:

“It is critically important now to bolster the resilience of the Reef, and to maximise its natural capacity to recover. But the reef is no longer as resilient as it once was, and it’s struggling to cope with three bleaching events in just 18 years.”

Video – Corals dying too fast

In this ARC Center video, a news anchor informs that in some parts of the Great Barrier Reef, there is less than five percent live coral cover.