A huge Roman Villa belonging to a wealthy family over 1,400 years ago was unearthed by a team of electricians while they were digging up a garden to lay an electric cable to supply power to a barn in Wiltshire in England.

Rug designer, Luke Irwin and his wife had recently bought a farmhouse in Brixton Deverill, a small village approximately four miles south of Warminster.

An old barn near the farmhouse had no electrical supply, and Mr. & Mrs. Irwin wanted their children to be able to play ping pong in it. So they called an electrical contractor to determine the best way to convert the barn.

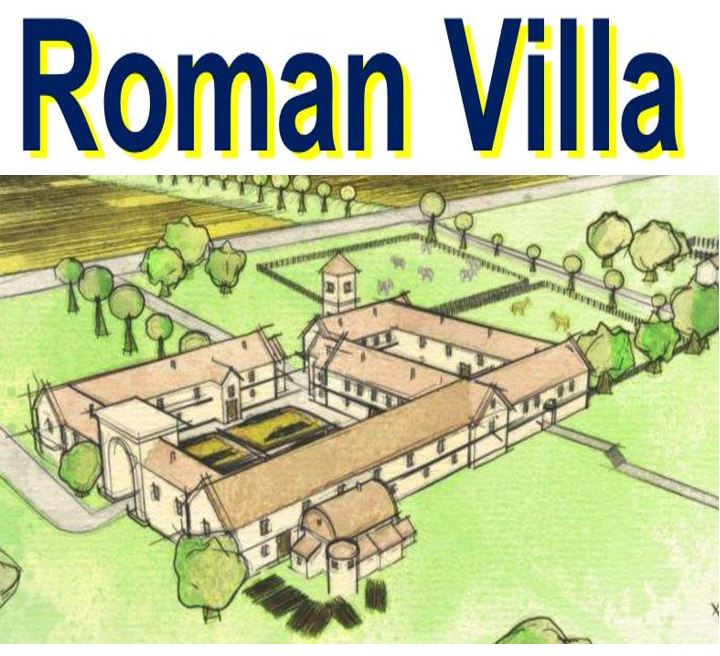

An artist’s impression of the palatial Roman villa that belonged to a very wealthy family. Had Mr. Irwin decided to connect an overhead cable to the barn, nobody would know today that the ancient villa existed. (Image: Historic England)

An artist’s impression of the palatial Roman villa that belonged to a very wealthy family. Had Mr. Irwin decided to connect an overhead cable to the barn, nobody would know today that the ancient villa existed. (Image: Historic England)

The electricians recommended connecting the barn via an overhead cable from the farmhouse. However, Mr. Irwin decided he wanted the cable to go under the ground. Had it not been for that fateful decision and his insistence, nobody would have known that an ‘extraordinarily well-preserved villa’ as well as an untouched mosaic had been buried under his land, undisturbed, for over 1,400 years.

The electricians started digging

The team of electricians started drilling a hole when suddenly one of them noticed he had hit a hard layer, approximately eighteen inches below the surface. They cleared the earth carefully and discovered pieces of mosaic.

Mr. Irwin knew immediately that they had discovered something remarkable, and probably of great historical significance.

Mr. Irwin said:

“No one since the Romans has laid mosaics as house floors in Britain. Fortunately we were able to stop the workmen just before they began to wield pickaxes to break up the mosaic layer.”

Tesserae – individual tiles formed in the shape of a cube – used in creating a mosaic, found at the Roman villa in Wiltshire. (Image: Historic England)

Tesserae – individual tiles formed in the shape of a cube – used in creating a mosaic, found at the Roman villa in Wiltshire. (Image: Historic England)

Wiltshire Archaeology Service called

On seeing the beautiful mosaic, Mr. Irwin halted the barn-conversion work and called the Wiltshire Archaeology Service, which invited Salisbury Museum and Historic England to investigate the discovery.

Salisbury Museum and Historic England carried out an 8-day excavation on part of the site. They confirmed that the mosaic had formed part of an extremely well preserved, complex villa which had been build between 175 and 220 AD.

It had been re-modelled several times right up into the middle of the 4th century. There was some evidence that the site was reused during the fifth century.

The Roman Villa

The structures found at Brixton Deverill are very similar to those found in the Chedworth Roman Villa in Gloucestershire, one of the largest Roman villas in Britain. This new discovery probably belonged to a family of great wealth and importance, archaeologists say.

Regarding this latest discovery, Historic England wrote:

“We believe that parts of the double-courtyard villa had three storeys, based on the very thick walls which survive to almost 1.5m high and 0.9m wide.”

“These are capped with a base for a timber frame so we understand that the ground floor walls were built in large blocks, with a second storey of timber, topped with a stone tile roof.”

Mosaic found at the Roman villa discovered in Wiltshire. (Image: Historic England. Credit: Wiltshire Archaeological Service)

Mosaic found at the Roman villa discovered in Wiltshire. (Image: Historic England. Credit: Wiltshire Archaeological Service)

They also unearthed hundreds of discarded oyster shells, a stone coffin of a Roman child, several coins, a perfectly-preserved Roman well, hunted wild animals, the bones of animals including a suckling pig, and stone roof tiles with nails still in place. The child’s coffin had held geraniums until it was identified.

The oysters had been artificially cultivated and brought live from the coast in barrels of salt water. According to the archaeologists, only extremely wealthy families would have had the resources to have so many live oysters carried across land.

Dr. David Roberts, an Archaeologist who works for Historic England, said:

“This site has not been touched since its final collapse around 1500 years ago and so has great potential to teach us about life in Roman and post-Roman Britain.”

“The discovery of such an elaborate and extraordinarily well-preserved palatial villa, undamaged by agriculture, is unparalleled in recent years and we think has great potential for further research.”

Among the extraordinary finds was a Roman child’s coffin via @WesternDaily https://t.co/YBWOFyyfOu pic.twitter.com/YmJ7LnMpU2

— Historic England (@HistoricEngland) April 17, 2016

The excavation work was carefully recorded following geophysical surveys by Archaeological Survey Ltd. (commissioned by Mr. Irwin) and volunteers from Salisbury Museum.

In order to better preserve the remains, the excavation trenches have been backfilled. If they had been left open, the walls and features left in the site by the archaeological team would have been endangered.

Post-Roman Remains

Post-built timber structures were built within the partly-ruined villa after the Roman period. These remains have the potential to provide us with useful insight into a little known period of British history – between the beginning of the 5th century and the completion of Saxon domination two centuries later.

Historians and anthropologists know very little about how the people in England at the time responded to the collapse of the Roman Empire – the mega-power of that period.

Historic England wrote:

“Historic England will continue to work with the owner, Salisbury Museum and Wiltshire Archaeological Service to explore future options for protecting and understanding this intriguing site.”

1400 year old site “unquestionably of enormous importance” https://t.co/SeDWsOqpXT

— Historic England (@HistoricEngland) April 17, 2016

The house that Mr. and Mrs. Irwin had recently bought was created out of two farm labourers’ cottages. It had been built in the centre of the ancient villa on a huge slab of Purbeck marble, which archaeologists think is probably of Roman origin.

Fortunately, this large villa was not destroyed following the collapse of the Roman Empire.

The discovery of the child’s coffin

In front of the Irwin’s kitchen window, out in the garden, was a long trough-shaped pot with some very tired geraniums. Dr. Roberts repeatedly asked the property’s new owner about it.

All Mr. Irwin knew was that it was already there when he moved in. He contacted the previous owner who said the same – the object of interest had been there before she bought the property in the 1980s.

Mr. Irwin asked Dr. Roberts why he was so interested in an old geranium pot that looked more like a cattle trough. Dr. Roberts responded that he believed it would well have been a Roman child’s coffin.

Regarding the coffin, which had been ‘hiding in plain site’ for so many hundreds of years, Mr. Irwin said:

“This is about eyes being open and accumulation of knowledge. It is seeing things in a different way – taking a knowledge you have for topography, seeing undulations in a field and being able to build a story of what is going on there.”

“To me it is quite staggering that what is effectively a palace that can lie unknown and undetected for over a thousand years. It is quite extraordinary.”

Video – An artist’s recreation of the Roman villa

This Lewis Irwin Rugs video shows the Roman villa as rendred by a video artist, based on the discoveries made at the excavation site.