Our ancient human ancestors developed compassion, kindness and a sense of beauty well before we started becoming intelligent, an archaeologist from the University of York informs in a new book.

Australopithecines, one of our prehistoric human ancestors that existed about three million years ago, had brains just one third the size of modern humans’. According to Dr. Penny Spikins, a Senior Lecturer in the Archaeology of Human Origins, at the Department of Archaeology, University of York, England, australopithecines carried pebbles shaped like babies’ faces.

There is evidence that Homo ergaster was caring for sick family members about 1.5 million years ago. Their brains were only 60% of the size of ours.

In her new book, author Penny Spikins argues that compassion, which emerged millions of years ago, lies at the heart of what makes us human. (Image: How Compassion Made Us Human)

Homo heidelbergensis adults were caring for disabled children about 450,000 years ago.

Human intelligence and the ability to communicate with sophisticated language is thought to have developed between 500,000 and 150,000 years ago.

In an interview with the Sunday Times, Dr. Spikins said:

“Human evolution is usually depicted as driven by intelligence, with empathy and deeper emotions following.”

“However, the evidence suggests it happened the other way round. Evolution made us sociable, living in groups and looking after one another, even before we had language. Our success since then, including the evolution of intelligence, all sprang from that.”

Dr. Spikins, who has published her research in a new book – “How Compassion Made Us Human” – says that archeological findings suggest that hitherto unknown levels of emotional depths were present even among our pre-human ancestors.

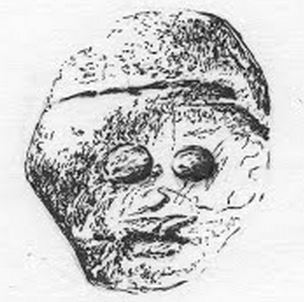

The Makapansgat pebble

One of the earliest pieces of evidence is the Makapansgat pebble (pebble with many faces), dating back 3 million years, found in a South African cave.

The Makapansgat pebble, picked out and brought to Makapansgat cave by an australopithecine 3m years ago. (Image: How Compassion Made Us Human)

Makapansgat pebble is a small, 260g (9oz) reddish-brown jasperite cobble with natural chipping and wear patterns that make it look like a human face. It is probably the oldest example of manuport (a natural object which has been moved from its original context by a human, but otherwise remains unmodified).

Australopithecines were our direct ancestors. Archeologists in the 1930s described them as killer ape-like creatures because archeological findings in a cave pointed to evidence of warfare – skulls and bones appeared to have been smashed.

Dr. Penny Spikins has been a lecturer in Early Prehistory at the University of York since 2004. (Image: University of York)

Their discovery inspired the early scenes in the movie 2001: A Space Odessy, which insinuated that aggression and fighting were two important factors in helping apes evolve into humans.

According to Dr. Spikins, australopithecines survived by cooperating rather than fighting. They were hunted by other animals.

Dr. Spikins said:

“What is remarkable is that this pebble was carried several miles back to its cave by an australopithecine. Did it remind them of a baby? It is impossible to tell for sure but this is not the only tantalising sign of something perhaps approaching tenderness.”

Early humans also appeared to have a sense of artistic beauty. A 250,000-year-old hand axe found at West Tofts, Norfolk, England, was found, made from a rock with a fossilized scallop shell. The shell had been placed on the axe with beauty in mind – it was the centerpiece of the tool.

Hand Axe Knapped Around Fossil Shell. Palaeolithic (100,000 to 10,000 BC). Length 13cm. (Image: Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

Dr. Spikins said:

“A uniquely human feeling lies behind both the creation of such finely crafted tools and caring for the vulnerable. It suggests early humans, from two million years ago, were emotionally similar to us.”

“The idea that we are all innately selfish, which comes from modern economics, has had a strong influence on how we interpret archeological finds but the evidence suggests that … early humans’ survival would have depended on co-operation: aggressive or selfish behaviour would have been very risky.”

Testimonials

Two authors made the following comments after reading Dr. Spikins’ book:

Robin Dunbar, author of Thinking Big: How the evolution of social life shaped the human mind, wrote:

“Archaeologists often seem to forget that our ancestors had an intensely social and emotional life. In this delightfully written book, Penny Spikins gives us some beautifully crafted insights into that ancient world.”

Paul Gilbert, author of The Compassionate Mind, wrote:

“Takes the reader on a fascinating new journey through the archaeological evidence for what makes humans unique.”