Humans can be surprisingly cruel, inflicting higher levels of pain on other people when under orders, compared to what they would do when choosing freely, a new study has found. Does that mean that the plea during the post-WWII trials at Nuremberg “I was following orders, it was not me,” was a valid one, or are we really in control of what we do, regardless of what people order us to do?

Researchers from the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium and University College London (UCL) reported in the peer-reviewed journal Current Biology (citation below) that when we follow orders we feel less responsible for our actions.

When we receive coercive instructions we feel less responsible for the outcomes of our actions, rather than saying we are less responsible, the scientists explained.

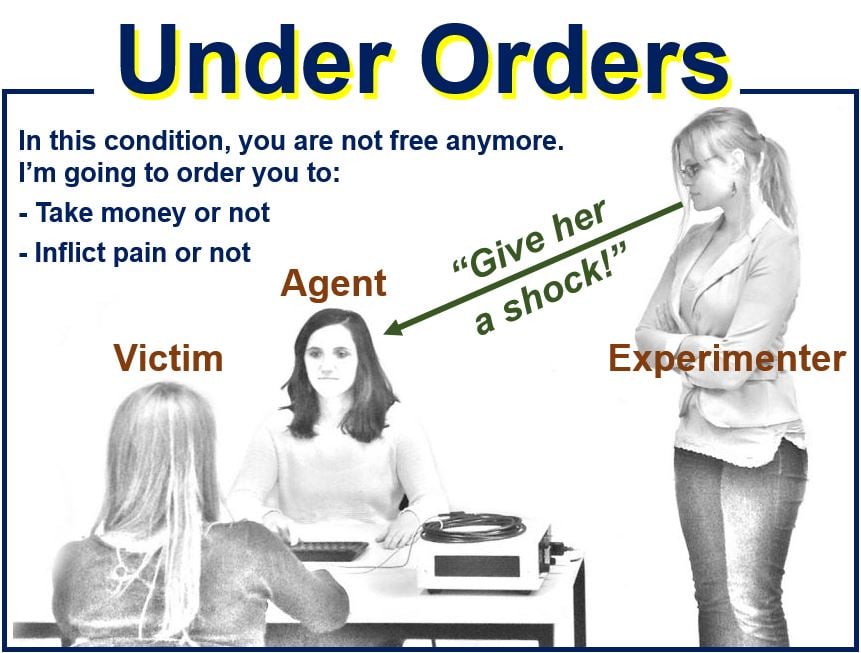

In the coercive situation, the experimenter ordered the agent at each trial either to take money from the other participant (financial harm group) or to deliver a shock (physical pain group). The experimenter stood right next to the agent and looked at her throughout the whole time. (Image: cell.com)

In the coercive situation, the experimenter ordered the agent at each trial either to take money from the other participant (financial harm group) or to deliver a shock (physical pain group). The experimenter stood right next to the agent and looked at her throughout the whole time. (Image: cell.com)

We are held responsible for our actions in most societies

In virtually all societies across the world, individuals are held responsible for all their actions. However, the defendant in court sometimes claims reduced responsibility because he or she was ‘only obeying orders’.

Most of us are generally skeptical regarding such a plea, because there is a clear motive of avoiding punishment. We wonder how responsible they would feel if they had not been caught and were not not facing possible punishment.

Several scientific studies, most notably the well-known Milgram Experiment, described by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram in 1963, concentrated on how readily or willingly people complied with coercive orders.

The Milgram Experiment measured participants’ willingness to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts which conflicted with their personal conscience.

The experiment found, surprisingly, that a significantly high proportion of people were prepared to obey, albeit unwillingly, even if they appeared to be causing serious injury or distress.

In this condition, the participants can choose freely what to do – whether or not to give an electric shock or financial penalty, or not. The experimenter does not interfere and looks away the whole time. (Image: cell.com)

In this condition, the participants can choose freely what to do – whether or not to give an electric shock or financial penalty, or not. The experimenter does not interfere and looks away the whole time. (Image: cell.com)

However, Milgram did not investigate the experience of being coerced.

Investigating the experience of being coerced

Senior author of this latest study, Professor Patrick Haggard, who works at UCL’s Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, and colleagues set out to investigate this experiment.

In one experiment, two study participants took turns to impose a financial penalty on each other. When a penalty was administered, that person received a small financial reward.

In another experiment, two participants gave each other electric shocks, and again were given a financial reward each time they administered a shock.

The shock-administrating devices were set to a level that a human can tolerate, but the maximum was above each participant’s pain threshold. In other words, the devices were capable of inflicting nasty pain, but could not kill or damage the other person.

In one situation, the participants could choose freely on each trial whether or not to give the other person a shock or penalty by pressing specific keys.

In a second situation, the person conducting the trial (experimenter) gave a coercive instruction to the participant, instructing them whether or not to give the other person a shock or administer a penalty.

Adolf Eichmann (pronounced [1906 – 1962) on trial in 1962, accused of managing the logistics of the mass deportation of Jews to ghettos and extermination camps in German-occupied Eastern Europe during WWII. He said he was acting ‘under orders’. He was executed in 1962. (Image: Wikipedia)

Adolf Eichmann (pronounced [1906 – 1962) on trial in 1962, accused of managing the logistics of the mass deportation of Jews to ghettos and extermination camps in German-occupied Eastern Europe during WWII. He said he was acting ‘under orders’. He was executed in 1962. (Image: Wikipedia)

After pressing the key, the participant would hear a tone, at a random delay of either 200, 500 or 800 milliseconds (ms).

In the experiments involving a shock or financial penalty, this occurred at the same time as the tone. On each trial, the participant had to estimate the interval, in milliseconds, between their action and the tone.

Time before tone a measure of perceived control

The perceived time gap between action and tone was used as a marker of a feeling of control over the action’s outcome, and therefore the feeling of responsibility.

In this study, the researchers showed that the time gap between the keypress action and the tone was perceived as shorter than a control condition where the participant’s hand was passively moved down onto a key, replicating previous results, and confirming that a smaller perceived interval is a useful marker of sense of control over the tone.

Most importantly, Prof. Haggard and colleagues found that coercive instructions lead to a longer perceived interval between action and tone, compared to when the action was freely chosen.

These results suggest that people feel less control over the outcomes of their actions when they are given orders, compared to when they decide independently.

This was confirmed when the participants were asked explicitly about their sense of responsibility after the experiment.

Even though the feelings of control depended strongly on the context of coercion versus choice, the results were the same on trials where the outcome was actually harmful as on trials where no harm was inflicted on the other person.

Furthermore, recordings of the brain activity involved in processing the outcome of the action showed less processing for outcomes occurred when the participant was under coercion, compared to outcomes of free choices.

Under orders we feel less responsible for actions’ outcomes

Prof. Haggard said:

“When you ask people explicitly about responsibility, they tend to report what they think reflects best on them. We wanted to know what people actually felt about the action as they made it, and about the outcome.”

“Time perception tells us something about the basic experiences people have when they act, not just about how they think they should have felt.”

“Our results suggest people who obey orders could actually feel less responsible for the outcomes of their action: they may not just be claiming that they feel less responsible. People appear to experience a sort of distance from the outcome of their actions when they are obeying instructions.”

“It’s important to distinguish between how our minds generate our subjective feelings of responsibility, and the objective facts of responsibility. Of course, just feeling less responsible does not mean that you aren’t responsible, and shouldn’t be held responsible by society. In the end, society has to deal with the objective facts of what an individual does.”

The researchers believe their findings may have wider social relevance in the real world.

We need to train order receivers and givers too

First author, Dr Emilie Caspar, said:

“There are many situations where people obey orders: in fact, society sometimes requires people to obey an order to do something unpleasant. Think of a soldier who is ordered to shoot at an enemy in the legitimate defence of his country.”

“Our study shows that people under orders may not feel responsible for what they do. Perhaps that explains why so many people appeared to obey coercive orders, in Milgram’s experiments. Our findings have several practical implications.”

“First, maybe people can be trained to feel more responsible: that might allow them to resist orders that are inappropriate. Second, our results could be particularly important for people who give orders. If people who follow orders feel a reduced sense of responsibility for their actions, then perhaps people who give orders should feel increased responsibility.”

For example, in some governments a minister is held responsible for his or her civil servants’ actions. It is important that society knows how to manage this kind of distribution of responsibility properly.

Prof. Haggard concluded:

“It is hard to see how society could function without a sense of responsibility. We therefore need to understand the factors that influence people’s feelings of responsibility, so we can manage those factors: it’s a topic where psychology and politics become quite close.”

Prof. Milgram’s original experiments were motivated by the trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, who argued that he sent Jews to their deaths because he was ‘just following orders’.

While the findings in this latest study in no way try to legitimize harmful actions, Prof. Haggard stressed, they do suggest that the ‘only obeying orders’ plea betrays a deeper truth about how an individual feels when acting under command.

Citation: “Coercion Changes the Sense of Agency in the Human Brain,” Emilie A. Caspar, Julia F. Christensen, Axel Cleeremans, Patrick Haggard. Current Biology 26, 1–8 March 7, 2016. DOI: org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.067.

Video – The Milgram Experiment

Prof. Milgram showed how humans are capable of surprising levels of cruelty when operating under orders.