There is a hummingbird that flies over 1300 miles (2000 km) without stopping, which is an incredible migration feat for such a tiny creature that weighs just 0.12 oz (3.4 g), says a team of researchers from the University of Southern Mississippi in the United States.

Theodore Zenzal and colleagues wrote about their study on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the journal The Auk: Ornithological Advances (citation below).

They say their study provides some of the first details of the tiny bird’s annual autumn journey from the eastern USA to Central America, showing that their migration peaks in September and that the older birds set off before the younger ones.

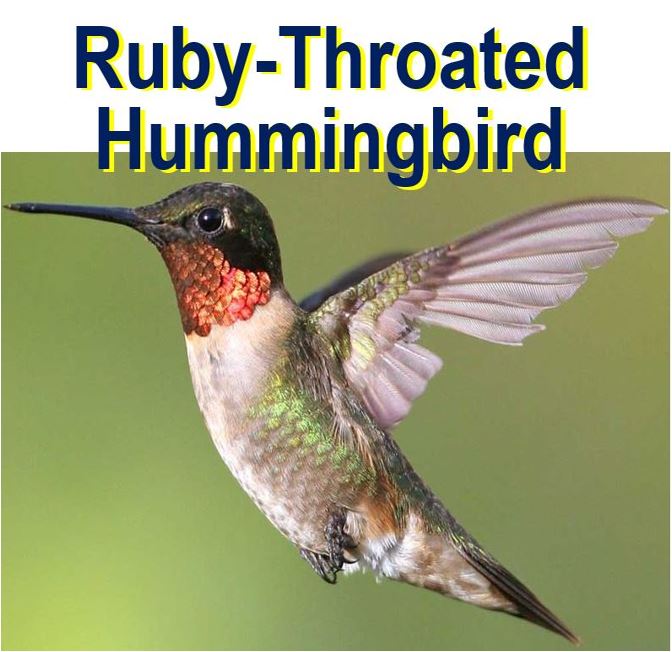

According to audubon.org: “The Ruby-throated Hummingbird beats its wings more than 50 times per second. Impressive migrants despite their small size, some Ruby-throats may travel from Canada to Costa Rica.” (Image: audubon.org)

According to audubon.org: “The Ruby-throated Hummingbird beats its wings more than 50 times per second. Impressive migrants despite their small size, some Ruby-throats may travel from Canada to Costa Rica.” (Image: audubon.org)

Older birds and males fly non-stop further and faster

Gathering data on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds passing through southern Alabama, the researchers found that they moved through the area between late August and late October. The older birds arrived earlier and in better condition.

They used a computer programme to estimate how far they flew based on their mass and wingspan, and found that the average hummingbird had a flight range of approximately 2,200 kilometres (1,367 miles).

Their programme predicted that the older birds and males were capable of travelling further non-stop than the younger ones and females.

According to their findings, the older birds are more experienced and socially dominant, and leave their breeding territories earlier and travel at higher speeds.

Ruby-throated hummingbird pair. The male (left) has a brilliant red throat, whitish underparts with dull greenish sides, and a moderately forked tail. The female has a whitish throat, the rest of its underparts are a dull greyish white, while its tail is rounded and broadly tipped white. (Image: press.princeton.edu)

Ruby-throated hummingbird pair. The male (left) has a brilliant red throat, whitish underparts with dull greenish sides, and a moderately forked tail. The female has a whitish throat, the rest of its underparts are a dull greyish white, while its tail is rounded and broadly tipped white. (Image: press.princeton.edu)

Do they cross the sea?

The researchers do not yet know whether Ruby-throated Hummingbirds fly across the Gulf of Mexico or around it. However, according to their flight-range calculations, most of them would be able to make it over the sea if weather conditions were favourable.

Zenzal, whose work was partly funded by the National Geographic Society, said:

“The most interesting thing, in my opinion, is how some of these birds effectively double their body mass during migration and are still able to perform migratory flights, especially given some of the heftier birds seem to barely make it to a nearby branch after being released.”

The research team captured the tiny birds in mist nets at Alabama’s Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge during the autumn migrations of 2010 – 2014. They banded and recorded data on an incredible 2,729 hummingbirds.

Members of a visiting documentary crew were charmed by the tiny hummingbirds.

Regarding the crew members, Zenzal said:

“All but one person on the crew was from Europe and most had never seen a hummingbird in real life, so you can imagine how fascinating these birds must have seemed.”

“During the course of filming, members of the crew would regularly ask me to place a hummingbird in their hand so they could release it.”

Hummingbird expert from UC Riverside, Chris Clark, said:

“Patterns we previously had hints of from small, anecdotal observations are documented here with a very large sample size. It’s interesting that the young of the year migrate after adults and are quite different in their stopover phenology.”

“This suggests there are substantial differences between flying south for the first time, as opposed to flying somewhere again as an adult. I think that further research on how young hummingbirds migrate, and the decisions they make, would be really interesting.”

Citation: “Stopover biology of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) during autumn migration,” Theodore J. Zenzal, Jr. and Frank R. Moore. The Auk: Ornithological Advances. April 2016, Vol. 133, No. 2, pp. 237-250. DOI: org/10.1642/AUK-15-160.1

The Costa’s hummingbird sings to its female through its feathers, a team of scientists in California reported.

Video – Hummingbird migration