As Iceland’s glaciers melt because of global warming, there is less weight pushing down on the land, which has started to rise, by as much as 1.4 inches annually in some areas, say scientists from the University of Iceland and the University of Arizona in a new study.

Imagine what happens to the surface of a trampoline as you get off it – it rises when your weight is gone. In Iceland’s case, the surface of the trampoline is the land (Earth’s crust).

The research team have also forecast that volcanic activity is likely to increase – about 12,000 years ago, during the last deglaciation, volcanic eruptions were more frequent and more intense.

The geoscientists have published their findings in the journal Geophysical Research Letters (citation at end of article).

There are 62 global positioning satellite receivers throughout Iceland that have helped geoscientists detect movement of the crust. (Image: Richard A. Bennett/UA Department of Geosciences)

The researchers say theirs is the first study to clearly show a direct link between the current rising of land levels resulting from deglaciation and today’s global warming which started in the 1980s.

At some of the sites studied by the team in south-central Iceland, the land was found to be rising by up to 1.4 inches each year.

Study first author, Kathleen Compton, a geosciences doctoral candidate, said:

“Our research makes the connection between recent accelerated uplift and the accelerated melting of the Icelandic ice caps.”

We have long-known that the land rises (rebounds) as glaciers melt and weigh less. There was uncertainty as to whether the current rises in land levels were due to modern ice loss or past deglaciation … until now, said Richard Bennett, associate professor of geosciences at the University of Arizona.

Faster land uplift means faster ice mass loss

“Iceland is the first place we can say accelerated uplift means accelerated ice mass loss.”

Ms. Compton, Prof. Bennett and Sigrun Hreinsdóttir of GNS Science in Avalon, New Zealand, used a network of sixty-two global positioning satellite (GPS) receivers that had been fixed to rocks across Iceland to determine how fast the land was rising.

They tracked the position of the GPS receivers over a period of several years – literally “watching” the rocks move – and calculated how much they had risen. This technique is known as geodesy.

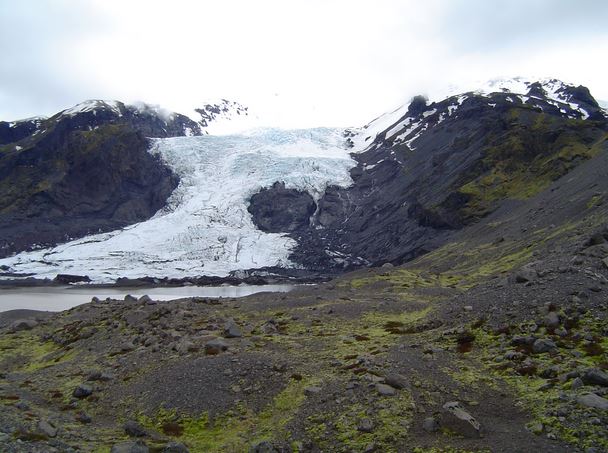

Gígjökull – an outlet glacier from Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland. As glaciers melt their reduced weight results in land uplift. (Photo: Ólafur Ingólfsson)

Their study showed that in Iceland’s case the crust’s current accelerating uplift was directly linked to the melting and subsequent thinning of the glaciers and global warming, the authors explained.

Climate change is altering the Earth’s surface

Prof. Bennett said:

“What we’re observing is a climatically induced change in the Earth’s surface.”

According to Prof. Bennett, about twelve thousand years ago, during the last deglaciation, volcanic activity in some parts of the island increased by a factor of thirty.

Other studies have predicted that as Iceland’s land rises because of global warming-induced ice loss, volcanic eruptions, such as the one in 2010 (Eyjafjallajökull), which had negative global economic effect, are going to become more frequent.

Many of the GPS receivers were placed in Iceland twenty years ago. Prof. Bennet and Dr. Hreinsdóttir installed 20 GPS receivers in 2006 and 2009, thus enlarging the coverage of the country’s geodesy network.

The geodesy network’s main function is to track geological activity, such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

In 2013, Prof. Bennett noticed that one of the long-standing stations in the center of the Island was showing that it was rising more rapidly. He and his team decided to check other nearby stations to see whether the same might be happening elsewhere.

Prof. Bennett said:

“The striking answer was, yes, they all do. We wondered what in the world could be causing this?”

Rate of land uplift linked to where ice caps are

After analyzing several years of signals from all 62 GPS receivers, the team found that the fastest rate of uplift was taking place in the area between several large ice caps. The rate of accelerating uplift went down the farther the receiver was from the ice cap region.

According to other geoscientists who had been measuring ice loss in Iceland, the rate of ice melting has been accelerating significantly since 1995. According to Iceland’s records, which date back to the 19th century, temperatures have been rising since 1980.

Ms. Compton used mathematical models to see whether the same annual rate of ice loss over an extended period could cause the land to rise at a faster rate. She found it could not. For uplift to be occurring at a faster rate, the glaciers had to be melting at an accelerating rate each year.

The team found that the ice-loss and the onset of rising temperatures corresponded closely with Ms. Compton’s estimates of when the uplift began. She said she was surprised at how well everything lined up.

Prof. Bennett said:

“There’s no way to explain that accelerated uplift unless the glacier is disappearing at an accelerated rate. Our hope is we can use current GPS measurements of uplift to more easily quantify ice loss.”

The team now plans to see how seasonal variations affect the land uplift rate, as ice caps shrink during the summer and grow in winter.

Citation: “Climate driven vertical acceleration of Icelandic crust measured by CGPS geodesy,” Kathleen Compton, Sigrun Hreinsdóttir, and Richard A. Bennett. Geophysical Research Letters. January 2015. DOI: 10.1002/2014GL062446.