Under the dry valleys in Antarctica there are several interconnected lakes and brine-saturated sediments that could sustain life, and if so, dramatically increase the likelihood of there being some types of lifeforms on Mars, says an international team of American, Danish and French scientists.

The researchers, from the Universities of Tennessee, California, Louisiana and Dartmouth College in the US, Aarhus University in Denmark, and Sorbonne Universités in France, wrote about their findings in the journal Nature Communications (citation below).

Co-author, Prof. Jill Mikucki, from the University of Tennessee, says they detected extensive salty groundwater networks using a new helicopter-borne electromagnetic mapping sensor system called SkyTEM.

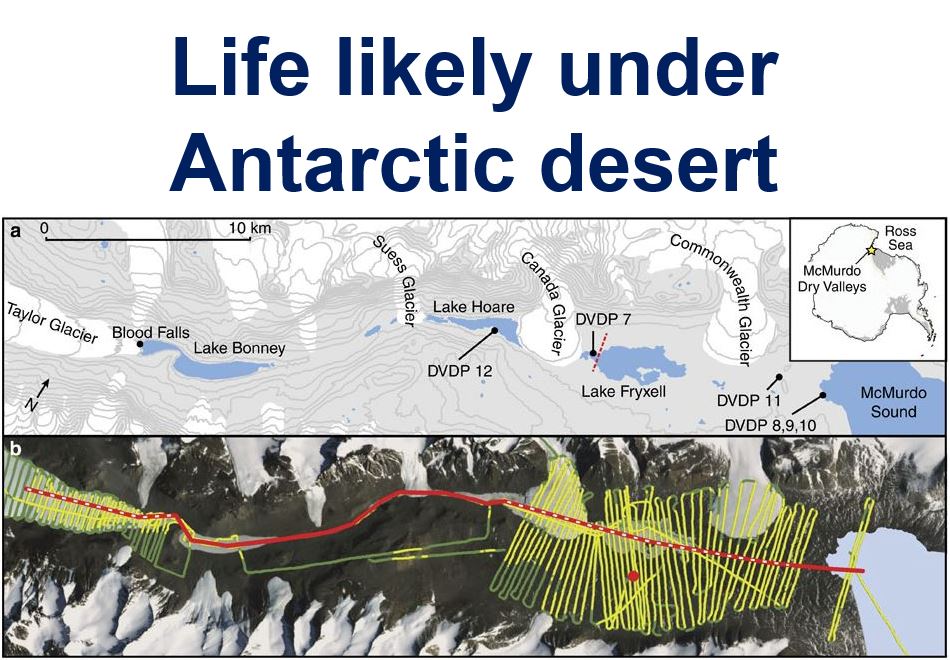

(Top picture) Map of major glaciers, lakes and DVDP (Antarctic Dry Valley Drilling Project) boreholes in Taylor Valley, Antarctica. Dotted red line shows the location of the Lake Fryxell DVDP geophysical survey. (Bottom picture) AEM flight lines in green, and survey lines for which data were processed in yellow. Terrain surveyed in the study in red. (Image: Nature Communications)

The authors say their study provides compelling evidence that underground brine-saturated sediments and lakes could support underground microbial ecosystems.

They believe their findings will help scientists better learn how Antarctica responded throughout history to climate change, Prof. Mikucki said. The data could provide insight into glacial dynamics.

Prof. Mikucki said:

“It may change the way people think about the coastal margins of Antarctica. We know there is significant saturated sediment below the surface that is likely seeping into the ocean and affecting the productivity of things that feed ocean food webs.”

“It lends to the understanding of the flow of nutrients and how that might affect ecosystem health.”

The scientists believe the newly discovered brines (water strongly impregnated with salt) harbor similar microbial communities in the deep, cold dark groundwater.

Could there be life in Mars brine?

By studying the brines, the team think they can gain insight into how microbes survive in harsh conditions, which could help in the exploration of a subsurface habitat on Mars. There are salts in the Martian soil that lower water’s freezing point, which allow briny films to form below the surface.

Prof. Mikucki and colleagues used the airborne sensor to produce sensitive imagery of the subsurface of the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica, the driest, coldest desert on Earth.

A helicopter embarks on a survey with the airborne electromagnetic sensor at Bull Pass in the Wright Valley, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. (Credit: J. Mikucki)

They used a helicopter to make the measurements, which meant vast areas of rugged terrain could be surveyed. They found that brines form extensive aquifers (underground layers of water-bearing rocks) below lakes, glaciers, and within permanently frozen soils.

The airborne sensor technology, which was developed at the University of Aarhus, was used for the first time in Antarctica during this study.

They also flew the sensor over one of the best-studied glaciers on Earth – the Taylor Glacier, which has a unique feature known as Blood Falls, where iron-rich brine from under the ground is released at the front of the glacier.

Blood Falls is known to harbor an active microbial community where organisms use sulphur (US spelling: sulfur) and iron compounds for growth and energy, and in the process facilitate rock weathering.

Researchers gathered data from the AEM sensor at Bull Pass in the Wright Valley, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. (Credit: J. Mikucki)

Co-author Peter Doran, professor of geology and geophysics at Louisiana State University, said:

“Prior to this discovery, we considered the lakes to all be isolated from one another and the ocean, but this new data suggests that there is a connection between the lakes and the ocean, which is very interesting and potentially a game changer in how we view the geochemistry and history of the lakes.”

Co-author Slawek Tulacyzk, a glaciologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said:

“Over billions of years of evolution, microbes seem to have adapted to conditions in almost all surface and near-surface environments on Earth. Tiny pore spaces filled with hyper-saline brine staying liquid down to -15 Celsius, or 5 degrees Fahrenheit, may pose one of the greatest challenges to microbes.”

“Our electromagnetic data indicates that margins of Antarctica may shelter a vast microbial habitat, in which limits of life are tested by difficult physical and chemical conditions.”

Citation: “Deep groundwater and potential subsurface habitats beneath an Antarctic dry valley,” J. A. Mikucki, E. Auken, S. Tulaczyk, R. A. Virginia, C. Schamper, K. I. Sørensen, P. T. Doran, H. Dugan & N. Foley. Nature Communications. Published 28 April, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7831.