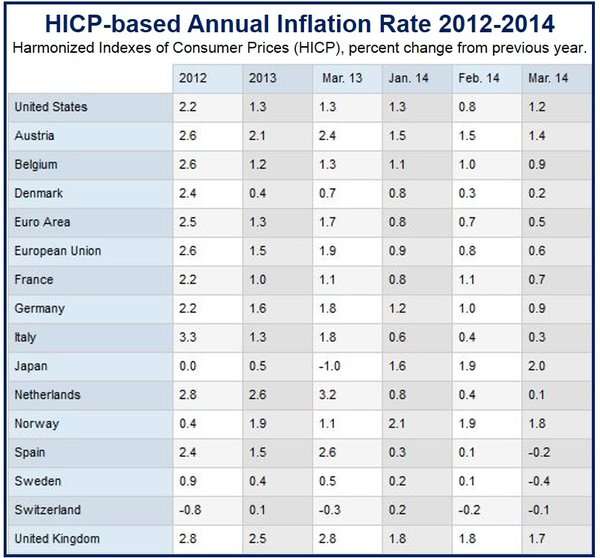

Low European inflation persists, particularly in the Eurozone, according to the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). In all European economies, with the exception of Switzerland, prices fell in March 2014.

Switzerland’s deflation fell from (minus) –0.2% in February to (minus) -0.1% in March, i.e. even though it was the exception regarding the European inflation trend, the country still saw prices falling.

The US inflation rate in March increased from 0.8% to 1.2% (annualized). However, it was still well below the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%.

In Japan, prices rose from from 1.9% in February to 2% in March.

Deflationary pressures in Europe

Elizabeth Crofoot, Senior Economist with the International Labor Comparisons program at The Conference Board, said:

“In March, Spain and Sweden joined Switzerland among the ranks of deflationary economies. Germany’s dip to below one percent inflation in March is a wake-up call that even the euro area’s largest economy is not immune to deflationary pressures.”

“For the euro area as a whole, the combination of low inflation and record unemployment suggests that inflation will remain low in the foreseeable future.”

(Source: The Conference Board)

March inflation rates were highest in:

- Japan: 2%

- Norway: 1.8%

- The UK: 1.7%

and lowest in:

- Sweden: -0.4%

- Spain: -0.2%

- Switzerland: -0.1%

While Switzerland has had recent episodes of falling prices, Sweden has not seen deflation since 1998, and Spain since the global financial crisis in 2009. A northern European country to report falling prices is a worrying development, economists say.

German inflation, at 0.9%, dipped below 1% for the first time in nearly four years.

There is concern that as Eurozone inflation moves further and further away from the European Central Bank’s target of 2% per year, the region could slide into a damaging period of persistent deflation. Inflation has been below 1% for six success months in the Eurozone.

Why the fear of deflation?

Those of us who are old enough to remember the high inflation years of the 1970s may wonder why falling prices are a bad thing.

The problem with persistently falling prices is that consumers and businesses postpone their purchases, because they know they can get better deals later on. If personal consumption slows down businesses sell less, and the economy overall slows down.

Long-term deflation leads to falling wages and increased debt-to-income ratios. If you have a mortgage and pay, for example, $800 per month in installments and your income is $4,000 per month, your mortgage payment represents one-fifth of your income. However, if your wages are cut to $3,200, the proportion will rise to one-quarter.

With persistent deflation people spend less, businesses earn less, there is less borrowing, debt-to-income ratios rise, unemployment starts to increase and the economy slows down. This is what Japan has been battling with for about twenty years.