Perfectly-preserved mummies dating as far back as 5050 BC have been degrading rapidly over the past ten years, gradually turning into black slime, say scientists from Harvard University, who suggest climate change could be the culprit.

More than two thousand years before the pharaohs were mummified in ancient Egypt, the Chinchorro, a hunter-gatherer people along the coast of modern-day Peru and Chile, developed sophisticated methods to mummify their community members, and not just elites, but also men, women, children, and even unborn fetuses.

According to radiocarbon dating, which estimates they were mummifying their dead as far back as 5050 BC, their mummies are the oldest around today.

A Chinchorro mummy at San Miguel de Azapa Museum in Arica, Chile. (Photo: Harvard University)

Chile preservationists turned to a Harvard scientist with a track record of solving mysteries related to threatened cultural heritage artefacts after noticing that the 7-thousand-year-old mummies had suddenly started to degrade.

Super ancient mummies suddenly turning into black ooze

The University of Tarapacá’s archaeological museum in Arica, Chile, houses nearly 120 Chinchorro mummies. That is where the alarming degradation was first detected. In some cases “they were literally turning into black ooze,” Harvard scientists wrote.

Marcela Sepulveda, professor of archaeology in the anthropology department and Archeometric Analysis and Research Laboratories at the University of Tarapacá in Chile, said during a recent visit to Cambridge:

“In the last ten years, the process has accelerated. It is very important to get more information about what’s causing this and to get the university and national government to do what’s necessary to preserve the Chinchorro mummies for the future.”

The chest of this mummy is literally turning into black ooze.

What was destroying these mummies?

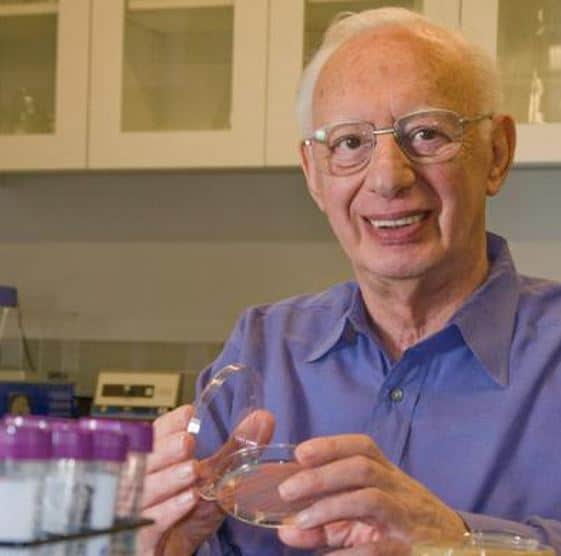

Prof. Sepulveda called on experts in North America and Europe to help solve the riddle of the degrading mummies, including Ralph Mitchel, a Gordon McKay Professor of Applied Biology, Emeritus at Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Prof. Mitchell has used his expertise in environmental microbiology to determine the causes of decay in a wide range of artefacts, from the Apollo space suits to the manuscripts to the walls of King Tutankhamen’s tomb.

Prof. Mitchell said:

“We knew the mummies were degrading but nobody understood why. This kind of degradation has never been studied before. We wanted to answer two questions: what was causing it and what could we do to prevent further degradation?”

It is amazing that more than 5,000 years before Christ, the Chinchorro people knew how to preserve the bodies of their deceased. (Image: www.historiayarqueologia.com)

A complicated process

Prof. Sepulveda explained that preparing the mummies thousands of years ago “was a complicated process that took time – and amazing knowledge.”

The Chinchorro would first extract the dead person’s organs and brains, and then reconstruct their body with fiber, fill the skull cavity with ash or straw, and sew everything back together – from jaw to cranium – with reeds.

The spine was kept straight with a stick that was tethered to the skull. The embalmer would sometimes keep the skin in place with patches of skin from other animals, such as sea lions.

Finally, they would cover the mummy with a paste, which varied in color depending on when it was done – black paste was made from manganese and was used in the oldest ones, later they used a red mixture made from ocher, with the most recent finds being covered with brown mud.

Prof. Mitchel and colleagues asked Prof. Sepulveda to send some samples. Both undamaged and degrading skin taken from the museum’s collection was sent.

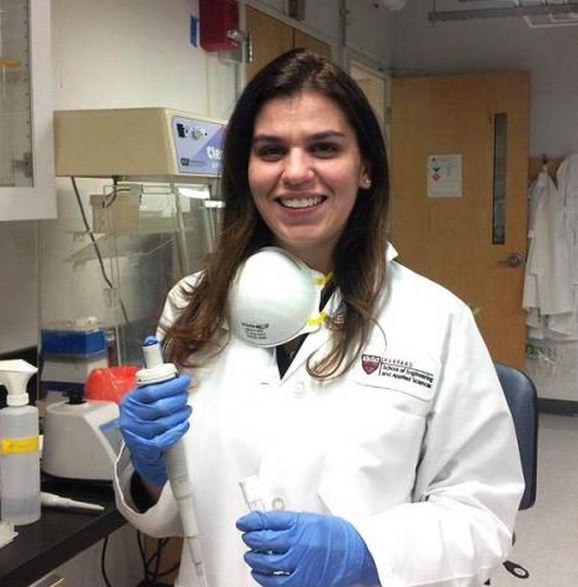

Alice DeAraujo, a research fellow in Mitchell’s lab, was given the task of receiving the samples.

Alice DeAraujo received the Harvard Extension School Dean’s Prize for Outstanding ALM Thesis for her research on the Chilean mummies. (Photo courtesy of Alice DeAraujo.)

Skin degradation was microbial

The scientists realized immediately that the degradation was microbial. They needed to determine whether a microbiome on the mummy’s skin was the culprit.

Prof. Mitchell said:

“The key word that we use a lot in microbiology is opportunism. With many diseases we encounter, the microbe is in our body to begin with, but when the environment changes it becomes an opportunist.”

Prof. Mitchell needed to answer a series of questions:

– Is the microbiome in these mummies different from normal ones found in human skin?

– Is there a different population of microbes?

– Does this population behave differently?

“The whole microbiology of these things is unknown,” Prof. Mitchell explained.

Prof. Mitchell and Ms. DeAraujo isolated the microbes present in both samples of degrading and unaffected skin. However, they did not have much skin to work with, and needed a surrogate – pig skin. They cultured the organisms in the lab and tested them to see what happened when the samples were exposed to different levels of humidity.

Atmospheric moisture levels linked to skin damage

Ms. DeAraujo acquired pig skin from colleagues at Harvard Medical School and started a series of tests. After finding that the pig samples started degrading after 21 days at high humidity, she repeated the results using the mummy skin samples, and confirmed that higher moisture levels in the air triggered skin damage.

Prof. Sepulveda had commented that humidity levels in Arica, where the museum is located, have been rising recently. Arica is known as the driest inhabited place on Earth, with annual rainfall of just 0.76 mm (0.03 inches).

According to DeAraujo’s analysis, the ideal humidity range for mummy conservation in the museum is between 40% and 60%. Any higher atmospheric moisture concentrations could lead to degradation, while lower levels could trigger damaging acidification. The researchers do not yet know what the ideal temperature and light ranges should be.

And the mummies outside museums?

Prof. Mitchell said that so far, the museum will be able to fine-tune humidity levels, and later (when the scientists have the data), light and humidity levels too. However, he says he is keen to solve an even larger challenge.

Prof. Ralph Mitchell is concerned about what might happen to the (possibly) hundreds of mummies in Chile and Peru that are not in museums. (Image: Harvard University)

Prof. Sepulveda and colleagues in Chile and Peru say there are maybe hundreds of Chinchorro mummies buried just beneath the sandy surface in valleys across the region.

During new construction and public works projects they are often uncovered. Higher humidity levels could also make the unrecovered mummies more susceptible to damage. In the museum it is relatively easy to control the environment and preserve the mummies, but what about those exposed to the natural environment?

Prof. Mitchell asks:

“What about all of the artifacts out in the field? How do you preserve them outside the museum? Is there a scientific answer to protect these important historic objects from the devastating effects of climate change?”

Twenty-first century science may help provide the solution to preserving the 7,000-year-old Chinchorro mummies, Prof. Mitchell believes. “You have these bodies out there and you’re asking the question: How do I stop them from decomposing? It’s almost a forensic problem.”

The following scientists also contributed to the research: Philippe Walter from the Laboratoire d’Archéologie Moléculaire et Structurale in Paris, and Vivien Standen, Bernardo Arriaza, & Mariela Santos of the University of Tarapacá in Chile.

The work was jointly funded by the Universidad de Tarapacá, Harvard SEAS, and the Consejo Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica in Chile.

Video – Are mummies being damaged by climate change?