Neanderthals in Europe were perhaps infected by tropical diseases that we, that is modern humans, carried out of Africa, says a team of scientists from the universities of Cambridge and Oxford Brookes. As both Neanderthals and modern humans were species of hominin, it would have been easier for infectious agents to jump populations.

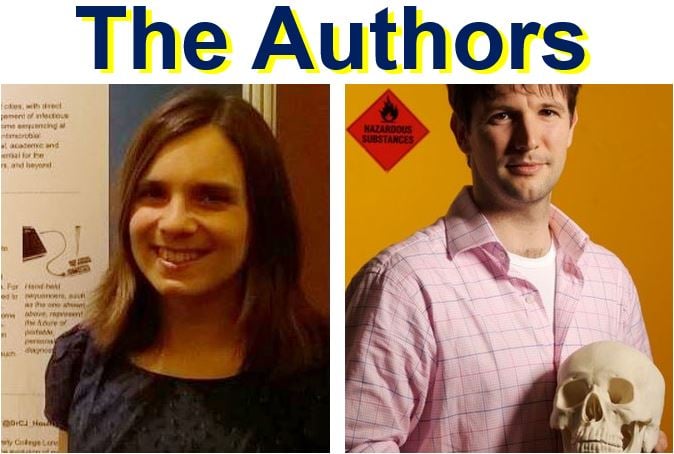

Dr. Charlotte Houldcroft, who works at Cambridge University’s Division of Anthropology, and Dr. Simon Underdown, a human evolution scientist from Oxford Brookes University, wrote in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology (citation below) that these tropical diseases brought from Africa might have contributed to the extinction of Neanderthals.

When our ancient ancestors moved out of Africa to Europe and Asia, where the Neanderthals lived, they interbred and infected the Neanderthals with tropical diseases. These diseases weakened them and contributed to their demise. (Image: catholic.org)

When our ancient ancestors moved out of Africa to Europe and Asia, where the Neanderthals lived, they interbred and infected the Neanderthals with tropical diseases. These diseases weakened them and contributed to their demise. (Image: catholic.org)

Many infectious diseases older than first thought

The authors have gathered and analysed the latest evidence gleaned from the pathogen genomes and DNA from ancient bones, and concluded that a number of infectious diseases are probably several thousands of years older than previously thought.

Evidence exists that our ancient ancestors interbred with Neanderthals and exchanged genes linked to disease. There is also evidence suggesting that viruses moved into humans from other hominin species while still in Africa.

The authors therefore argue that it makes sense to assume that modern humans may, in turn, have passed diseases to Neaderthals, and that – if we were interbreeding with them – we probably did.

Dr. Houldcroft said that several of the infections that modern humans passed to Neanderthals – such as types of herpes, stomach ulcers, tuberculosis and tapeworms – are chronic diseases that would have debilitated the hunter-gathering Neanderthals, undermining their ability to find food, which may have exacerbated their demise.

Neanderthals were hunter-gatherers. In order to get good to survive, they needed to be fit and in excellent health. The tropical diseases we spread to them were mainly chronic (long-term) ones, which undermined their ability to find food. (Image: Natural History Museum, London)

Neanderthals were hunter-gatherers. In order to get good to survive, they needed to be fit and in excellent health. The tropical diseases we spread to them were mainly chronic (long-term) ones, which undermined their ability to find food. (Image: Natural History Museum, London)

Foreign pathogens catastrophic for Neanderthals

Dr. Houldcroft said:

“Humans migrating out of Africa would have been a significant reservoir of tropical diseases. For the Neanderthal population of Eurasia, adapted to that geographical infectious disease environment, exposure to new pathogens carried out of Africa may have been catastrophic.”

“However, it is unlikely to have been similar to Columbus bringing disease into America and decimating native populations. It’s more likely that small bands of Neanderthals each had their own infection disasters, weakening the group and tipping the balance against survival.”

Modern techniques developed over the past few years mean scientists are now able to peer into the distant past of modern disease by unravelling its genetic code, as well as extracting DNA from the fossils of our earliest ancestors to identify traces of disease.

Dr. Houldcroft, who also studies modern infections at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, and Dr. Underdown explain in the journal that genetic data suggests that several infectious diseases have been ‘co-evolving with humans and our ancestors for tens of thousands to millions of years.’

Many diseases pre-date agriculture

Scientists have long believed that infectious disease exploded when humans turned from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture about 8,000 years ago. Human populations became denser and more sedentary, co-existing with livestock, thus creating a perfect storm for pathogens to spread.

The authors say that according to latest evidence, disease had a much longer ‘burn in period’ that pre-dates agriculture.

Dr. Charlotte Houldcroft is an Infectious Diseases Researcher at the University of Cambridge. Dr. Simon Underdown is Principal Lecturer in Biological Anthropology at Oxford Brookes University. (Images: (Left – twitter.com. Right – brookes.ac.uk)

Dr. Charlotte Houldcroft is an Infectious Diseases Researcher at the University of Cambridge. Dr. Simon Underdown is Principal Lecturer in Biological Anthropology at Oxford Brookes University. (Images: (Left – twitter.com. Right – brookes.ac.uk)

In fact, they say that several diseases traditionally classed as ‘zoonoses’ – transferred from animals into humans – such as tuberculosis, were actually transmitted the other way round, i.e. from humans into livestock. A zoonosis (zoonotic disease or zoonoses -plural) is a disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans or vice-versa.

Dr. Houldcroft said:

“We are beginning to see evidence that environmental bacteria were the likely ancestors of many pathogens that caused disease during the advent of agriculture, and that they initially passed from humans into their animals.”

“Hunter-gatherers lived in small foraging groups. Neanderthals lived in groups of between 15-30 members, for example. So disease would have broken out sporadically, but have been unable to spread very far. Once agriculture came along, these diseases had the perfect conditions to explode, but they were already around.”

Human-to-Neanderthal transmission must have occurred

No hard evidence has so far been uncovered showing that infectious diseases were transmitted between humans and Neanderthals. However, considering the overlap in geography and time, and not least the evidence of interbreeding, the authors are convinced it must have occurred.

Neanderthals would have adapted to the pathogens of their European environment. Evidence suggests that humans benefited from receiving genetic components through interbreeding that gave them protection from some of these: types of bacterial sepsis – blood poisoning occurring from infected wounds – and encephalitis caught from ticks that exist in Siberian forests.

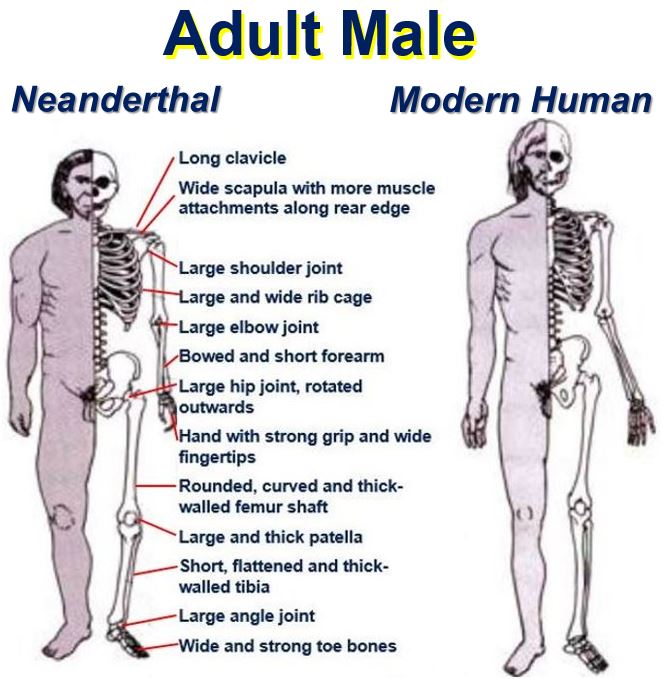

While modern humans and Neanderthals were genetically quite similar, there were several physical differences. In 2014, biomedical reporter Ewen Callaway wrote in Nature that when the two species interbred, the hybrid offspring probably suffered from significant fertility problems.

While modern humans and Neanderthals were genetically quite similar, there were several physical differences. In 2014, biomedical reporter Ewen Callaway wrote in Nature that when the two species interbred, the hybrid offspring probably suffered from significant fertility problems.

The humans, unlike their Neanderthal cousins, would have been adapted to tropical (African) diseases, which they would have brought with them during several waves of expansion into Europe and Asia.

The authors describe Helicobacter pylori, a gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium that causes stomach ulcers, as a prime candidate for a disease that early humans may have passed to Neanderthals.

H. pylori is estimated to have first infected humans in Africa between 88,000 and 116,000 years ago, and reached Europe after 52,000 years ago. According to the most recent evidence, Neanderthals died out about 40,000 years ago.

Another candidate is the virus known to cause genital herpes – herpes simplex 2. Evidence preserved in the genome of this disease suggests that it was transmitted to humans 1.6 million years ago in Africa from another, currently unknown hominin species, that in turn acquired it from chimpanzees.

Dr. Houldcroft said:

“The ‘intermediate’ hominin that bridged the virus between chimps and humans shows that diseases could leap between hominin species.”

“The herpesvirus is transmitted sexually and through saliva. As we now know that humans bred with Neanderthals, and we all carry 2-5% of Neanderthal DNA as a result, it makes sense to assume that, along with bodily fluids, humans and Neanderthals transferred diseases.”

Neanderthal extinction caused by combination of factors

There are several theories that try to explain how Neanderthals died out, from climate change to an early human alliance with wolves resulting in domination of the food chain.

The authors believe the demise of Neanderthals was caused by a combination of factors “and the evidence is building that spread of disease was an important one,” Dr. Houldcroft added.

“As Neanderthal populations became more isolated they developed very small gene pools and this would have impacted their ability to fight off disease. When Homo sapiens came out of Africa they brought diseases with them.”

“We know that Neanderthals were actually much more advanced than they have been given credit for and we even interbred with them. Perhaps the only difference was that we were able to cope with these diseases but Neanderthals could not.”

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors wrote:

“Coupled with pathogen genomics, this approach supports the view that many infectious diseases are pre-Neolithic, and the list continues to expand.”

“The transfer of pathogens between hominin populations, including the expansion of pathogens from Africa, may also have played a role in the extinction of the Neanderthals and offers an important mechanism to understand hominin–hominin interactions well back beyond the current limits for aDNA extraction from fossils alone.”

Citation: “Neanderthal genomics suggests a pleistocene time frame for the first epidemiologic transition,” Charlotte J. Houldcroft &Simon J. Underdown. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 10 April, 2016. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.22985.

Video – Neanderthals and US

In this 2014 Natural History Museum (London) video, Human Origins expert, Chris Stringer, tells us how recent genetic discoveries have changed our understanding of the overlap of several thousands of years between Neanderthals and modern humans.