If you want to encourage panda love and have lots of panda babies you have to let them choose their mate, i.e. mate preference is king in the panda world. You need to focus less on genetic matches, ovulation cycles, etc. If you don’t let pandas choose their mate, you will have a much harder time getting them to reproduce, a team of zoologists explained in the academic journal Nature Communications.

Pandas are not that different from humans – most of them are not keen on arranged marriages. If the chemistry is not there, neither is the attraction, and consequently neither are the cubs.

The giant panda is close to extinction in the wild. Scientists have devised all kinds of conservation breeding programmes in the hope of reviving a dwindling population. Endless studies have faced the challenges of female pandas’ limited ovulation cycles and a very small window for conceiving. Female pandas ovulate only once a year and have a 2-to-3-day window for conceiving.

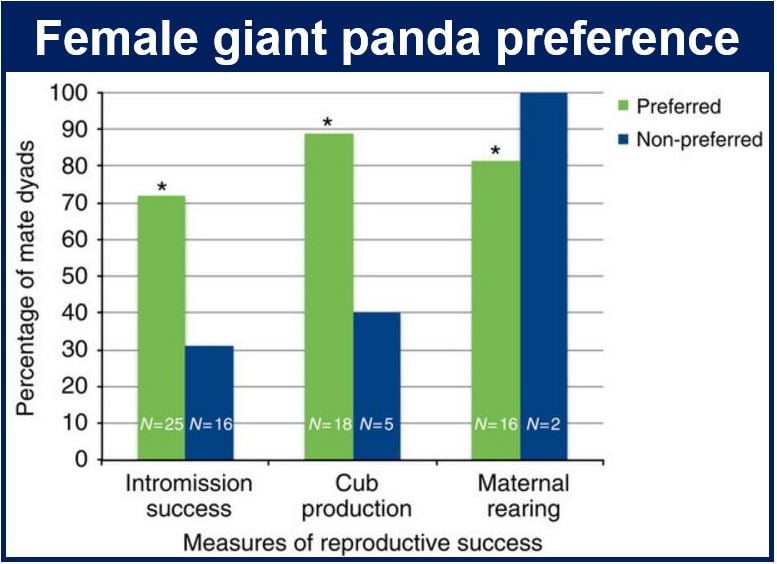

Female panda reproductive performance was notably higher when mated with preferred than non-preferred partners. Intromission (inserting penis into vagina) was more than twice as likely with preferred males and among those that copulated females were approximately two times more likely to produce a cub with a preferred male. (Image: Nature Communications)

Female panda reproductive performance was notably higher when mated with preferred than non-preferred partners. Intromission (inserting penis into vagina) was more than twice as likely with preferred males and among those that copulated females were approximately two times more likely to produce a cub with a preferred male. (Image: Nature Communications)

Apart from getting the timing right, researchers have written a great deal about the compatibility challenge. Breeding pairs have historically been placed together because their genes ‘matched’. However, this has not often resulted in a cub. Scientists have even turned to Viagra and ‘panda porn’ to get the fussy animals in the mood.

Mate preference matters more than genetic compatibility

In a new study led by Portland State University biology alumna Meghan Martin-Wintle, Ph.D. ’14, the researchers found that successful panda breeding and cub survival are influenced much more by mate preference than genetic compatibility.

The researchers carried out an experiment in a Chinese zoo where forty pandas were allowed to choose between two potential mates. Females would signal which male they preferred by scent making, interactions through a mesh barrier and chirping.

Male pandas were also allowed to choose. When compatibility was found, i.e. the panda feelings were mutual, the chances of them having a cub was 80% higher compared to pairs that were not allowed to choose their mate.

Male panda mate preference also had a significant effect on reproductive measurements, with males achieving intromission more than twice as frequently with preferred females than with non-preferred females. For those that did copulate, those mating with preferred females were more likely to produce cubs than those mating with non-preferred females. The study also found that older males had higher rates of intromission and cub production. (Image: Nature Communications)

Male panda mate preference also had a significant effect on reproductive measurements, with males achieving intromission more than twice as frequently with preferred females than with non-preferred females. For those that did copulate, those mating with preferred females were more likely to produce cubs than those mating with non-preferred females. The study also found that older males had higher rates of intromission and cub production. (Image: Nature Communications)

Conservation programmes must include mate choice

Martin-Wintle said:

“This suggests that incorporating mate choice could make a huge difference for the success of many conservation breeding programmes.”

“Giant pandas number fewer than 2,000 in the wild. If we can produce more individuals through these kinds of programs, we’ll have a larger surplus for reintroduction.”

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors wrote:

“If managers were to incorporate mate preferences more fully into breeding management, the production of giant panda offspring for China’s reintroduction programme might be greatly expedited.”

“When extended to the increasing numbers of species dependent on ex situ conservation breeding to avoid extinction, our findings highlight that mate preference and other aspects of informed behavioural management could make the difference between success and failure of these programmes.”

Meghan Martin-Wintle, who is currently a Post Doctorate Associate at San Diego Zoo Global, carried out this research while studying for her Ph.d. at Portland State University with Oregon Zoo. (Image: www.pdx.edu)

Meghan Martin-Wintle, who is currently a Post Doctorate Associate at San Diego Zoo Global, carried out this research while studying for her Ph.d. at Portland State University with Oregon Zoo. (Image: www.pdx.edu)

Captive breeding helping species survive

In 2012, the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums informed that 31 of the 33 animal species classified as ‘Extinct in the Wild’ on the IUCN Red List are actively bred in captivity in aquariums and zoos. Some species, such as the California condor, would today be completely extinct if it weren’t for captive breeding.

The findings in this latest study mirrored what Martin-Wintle, David Shepherdson, Oregon Zoo deputy conservation manager, and others had discovered in a previous study on Columbia Basin pygmy rabbits, an endangered Pacific Northwest native that was successfully bred at Oregon Zoo and reintroduced.

“Zoos are in a unique position to protect endangered species, captive breeding being only one example of how we can help. Of course, breeding programs can only be successful if we have suitable and safe habitat to reintroduce animals into.”

“Wildlife conservation takes many tools, from habitat protection to community support and advocacy. Captive breeding is only one of the tools in the toolbox.”

For successful giant panda breeding, they must be allowed to choose their mate.

For successful giant panda breeding, they must be allowed to choose their mate.

Martin-Wintle added:

“The take-home message is that we should probably conduct more of this kind of research with other conservation breeding programs in other species.”

Oregon Zoo partnerships with graduate students

Martin-Wintle is one of several Portland State students to carry out research together with Oregon Zoo. The partnership provides biology graduate students a research opportunity and the benefit of being mentored by both a scientist from Oregon Zoo and their faculty advisor.

Debbie Duffield, a Portland State University professor of Biology and Martin-Wintle’s advisor, said:

“The partnership between Portland State University Biology and the Oregon Zoo has been a fantastic opportunity for our students. They are conducting research that can lead to important changes in the way we understand and approach saving endangered species.”

The study was funded by a Future of Wildlife grant awarded by the Oregon Zoo Foundation in 2011.

Citation: “Free mate choice enhances conservation breeding in the endangered giant panda,” Meghan S. Martin-Wintle, David Shepherdson, uiquan Zhang, Hemin Zhang, Desheng Li, Xiaoping Zhou, Rengui Li & Ronald R. Swaisgood. Nature Communications 6. Article number: 10125. December 15, 2015. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms10125.

Video – Giant panda bears in the forest – David Attenborough

In this BBC video, Sir David Attenborough talks about giant pandas, the only bears known to be active during the winter months.