A team of researchers has developed a new way to extract moisture from the air and convert that water into electricity.

Wearable Devices

Their creation could be a blessing for people who must wear electronic devices, especially those with healthcare applications that need to be worn continuously.

-

Healthcare wearables

For the past decade, wearable devices have become increasingly popular. In the healthcare sector, there are fitness trackers, ECG monitors, blood pressure monitors, glucose monitors, pulse oximeters, and wearable cardiac monitors, to name just a few.

-

Batteries and Wireless Power Transfer

They currently run on traditional batteries. However, they do not last very long if the user must wear them continuously, and they are often too rigid.

Wireless power transfer techniques are a solution in some cases, but they have a limited range and are not portable.

Getting energy out of thin air!

Professor Seokheun “Sean” Choi, assistant professor Anwar Elhadad, and PhD student Yang “Lexi” Gao, all from State University of New York at Binghamton, found a way to generate electricity by pulling moisture from the air.

They wrote about their research in the peer-reviewed academic journal Small (citation below).

Choi said:

“Wearable electronics will use energy-harvesting techniques in the future, but right now, the techniques are very irregular in time, random in location and inefficiently converted. The reason why I was interested in this topic is that the moisture in our air is ubiquitous, and I realized that energy harvesting from moisture is very easy.”

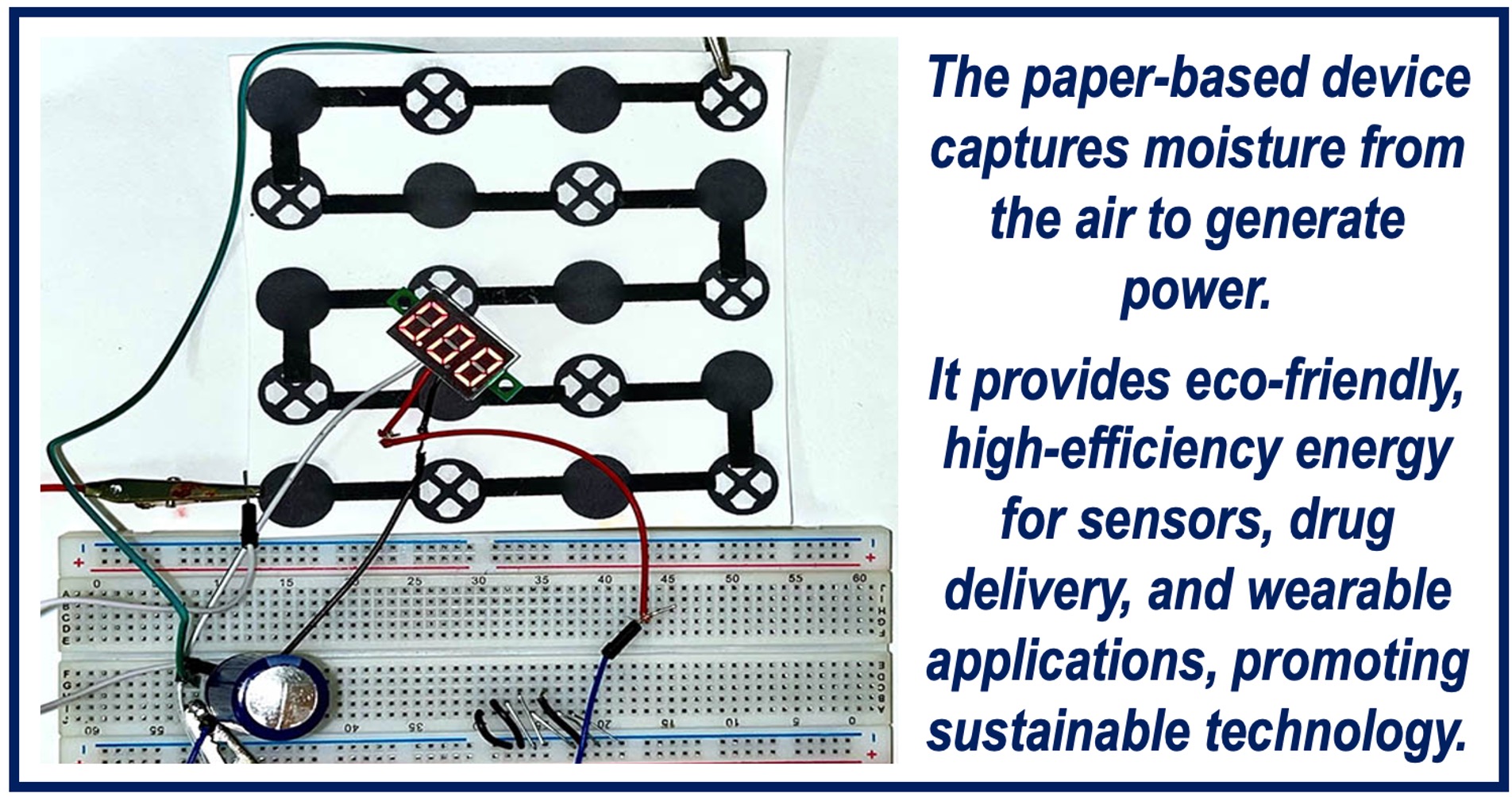

Building on 15 years of research into biobatteries at Choi’s Bioelectronics and Microsystems Lab, the generator utilizes bacterial spores as the “functional group” to break down water molecules into positive and negative ions.

The paper’s capillaries – a microporous structure – absorb the spores, creating a concentration gradient of positive ions. This imbalance generates an electric charge.

By adding a Janus paper layer that is *hydrophobic on one side and *hydrophilic on the other, moisture absorption is enhanced. This draws water molecules into the device and retains them until they are processed.

* Hydrophobic means water-repelling, and hydrophilic means water-attracting. For example, a duck’s feathers are hydrophobic, repelling water and keeping the bird dry. In contrast, a chicken’s feathers are more hydrophilic, allowing water to penetrate and soak through.

Environmentally Friendly Paper-Based Devices

The study extends Choi’s ongoing exploration of papertronics, which focuses on creating fully paper-based devices that are flexible, wearable, scalable, and disposable in an environmentally friendly way.

He envisions the moist-electric generator as a groundbreaking technology for applications such as low-power sensors, drug delivery systems, and electrical stimulation.

The researchers say they are pursuing the following improvements and refinements:

- Developing a method for energy storage.

- Greater power output.

- Integrating their technology with other energy-harvesting techniques.

- Shrinking the device to match the scale of micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS).

Choi added the following with a laugh:

“The size of one device is too big for me. I’m a MEMS guy! By decreasing each individual unit and connecting more cells within a small footprint, we can improve the power density significantly. Also, because we are using paper, we can try many other ideas, including origami techniques.”

Most researchers are developing long-term wearable devices. Choi, however, is going in the opposite direction. He is focusing on disposable devices that won’t lead to mountains of electronic waste.

Choi oncluded,

“I don’t want to wear something all day for four months. I want to use it for short time and then throw it away — so in that way, paper is the best.”

Citation

Gao, Y., Elhadad, A., & Choi, S. A Paper-Based Wearable Moist–Electric Generator for Sustained High-Efficiency Power Output and Enhanced Moisture Capture. Small, 2408182. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202408182