In the PISA problem-solving test, students from Korea and Japan came top. Students who do well in the OECD PISA first assessment of creative problem-solving are rapid learners, highly inquisitive, and skilled at solving unstructured problems in unfamiliar contexts.

A total of 85,000 students from 44 nations and economies did the computer-based test, which involved real-life situations to gauge the skills utilized by young people when faced with everyday problems, such as finding the fastest route to a destination or setting a thermostat.

Chinese Taipei, Shanghai-China, Hong-Kong China, Macao-China and Japan also ranked among the top-performing economies, while students from Belgium, the US, Germany, the Czech Republic, Italy, the Netherland, France, Estonia, England, Finland, Australia and Canada scored above the OECD (Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation) average.

Problem solving versus academic tests

While some countries did well on school subjects like science or mathematics, their students struggled with the problem-solving test. Conversely, kids in Japan, the US and UK were much better at problem-solving than in key school subjects.

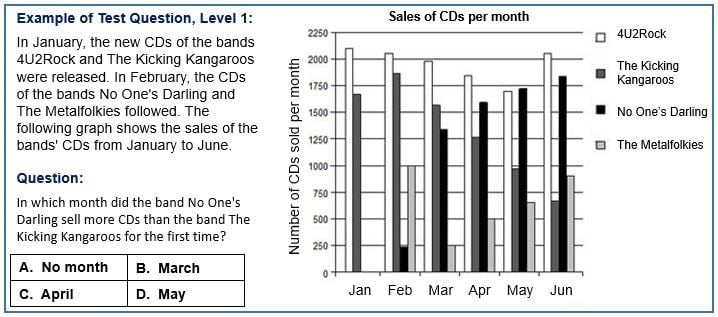

Example of mathematics question, level 1. There are six levels. (Source: OECD PISA Sample Questions)

Andreas Schleicher, acting Director of Education and Skills at the OECD, said:

“Today’s 15-year-olds with poor problem-solving skills will become tomorrow’s adults struggling to find or keep a good job. Policy makers and educators should reshape their school systems and curricula to help students develop their problem-solving skills which are increasingly needed in today’s economies.”

While 11.4% of 15-year-olds across OECD nations could solve the most complex problems, the figure in Japan, Korea and Singapore was over 20%.

However, across OECD nations about 20% of students were able to solve only the simplest problems, suggesting they do not have the skills required in the modern workplace.

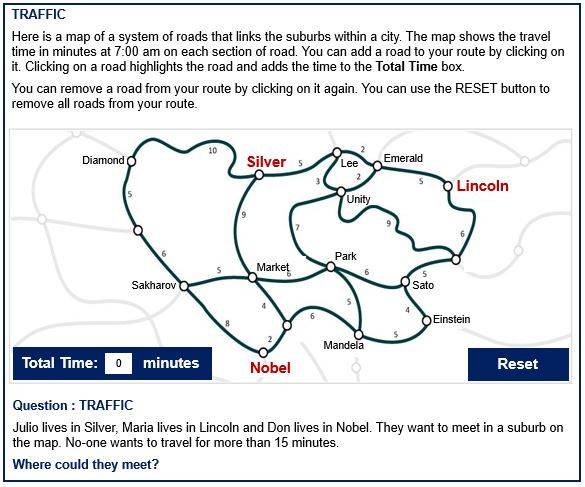

An example of a problem-solving question. (Source: OECD PISA problem-solving question)

Gender gap in the PISA problem-solving test

Among the low-performing students, the gender gaps in problem solving were small, according to the report. With the exception of Norway, Finland and Australia, the highest performing 15-year-olds were boys. Across OECD countries for every three top-performing boys there were two top-performing girls in problem solving.

According to a communique by the OECD “The impact of socio-economic status on problem-solving is much weaker than for the other PISA subjects of mathematics, reading and science: in France and Spain, for example, the relationship between socio-economic background and performance is only half as strong as in maths. But disadvantaged students are still twice as likely on average to score at the very lowest level compared to their more advantaged peers.”