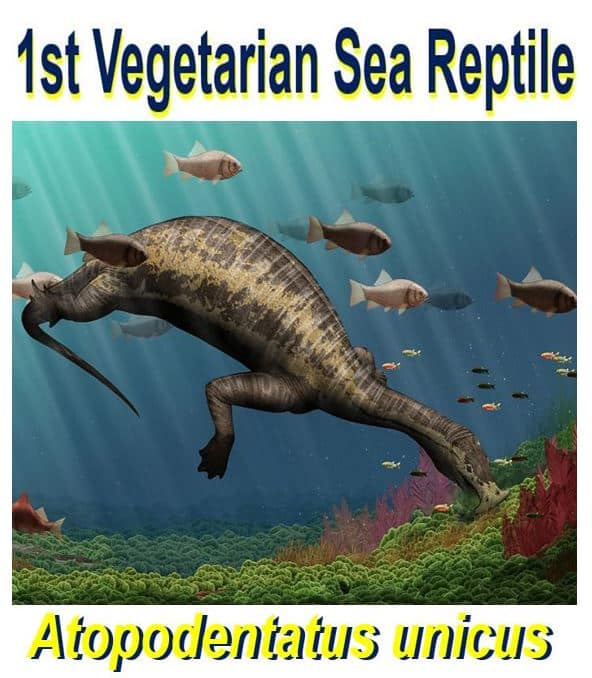

A strange-looking ‘hammerhead’ crocodile-sized plant eating marine reptile fossil, that existed about 242 million years ago, was probably the first known example of a vegetarian sea reptile, says a team of scientists from China, the US and Scotland.

Some bizarre-looking animals emerged in the wake of one of Earth’s greatest mass extinctions. That includes this vegetarian marine reptile that had an amazing hammerhead skull – a shape hitherto never seen in the reptilian fossil record.

The unusual creature, called Atopodentatus unicus, was first described two years ago based on a number of fragmentary fossils that had been unearthed. Its name is a blend of Greek and Latin for ‘unique and stange-toothed’.

When the first fossil fragments were discovered, scientists initially thought the creature had a dietary lifestyle similar to that of the modern flamingo, scooping with its downturned beak into sediment on the seafloor for prey. However, they later concluded that the animal was a herbivore, and probably the earliest vegetarian marine reptile. (Image: Science Advances)

When the first fossil fragments were discovered, scientists initially thought the creature had a dietary lifestyle similar to that of the modern flamingo, scooping with its downturned beak into sediment on the seafloor for prey. However, they later concluded that the animal was a herbivore, and probably the earliest vegetarian marine reptile. (Image: Science Advances)

At first scientists thought it was a carnivore

At the time, paleontologists (fossil scientists) believed the reptile, which was two-to-three metres long, had a downturned snout like a flamingo, that it used to stir up sediments on the seafloor as it foraged for mud-dwelling life forms.

However, newer and better-preserved fossils suggest that this animal, which lived in what today is south-central China 243-244 million years ago, had a quite different dietary lifestyle.

The front of its snout, which was very broad and T-shaped, was filled with chisel-like, stubby teeth, while the sides of its jaws had a series of closely-spaced, needle-shaped teeth, the research team reported in the latest issue of the journal Science Advances (citation below).

Such an arrangement of teeth would have been completely useless for chewing prey.

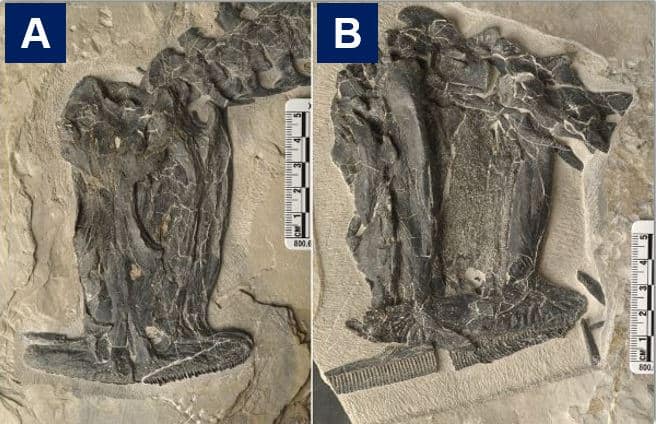

Prepared skulls of A. Unicus. (A) exposed in dorsal view. (B) exposed in ventral (underside) view. (Image: Science Advances. Credit: W Gao, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.)

Prepared skulls of A. Unicus. (A) exposed in dorsal view. (B) exposed in ventral (underside) view. (Image: Science Advances. Credit: W Gao, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.)

The authors Li Chun, from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China, Olivier Rieppel, who works at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, USA, and Nicholas Fraser, from the National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh, say that Atopodentatus most likely used its front teeth to chip algae and other plant life from rocky surfaces and then, with mouth closed, forced mouthfuls of water through its side teeth, which would have acted as a filter.

If what they suggest was the case, and most experts believe it probably was, Atopodentatus was the earliest vegetarian among marine reptiles we know of.

Overall, the animal is so bizarre that it is hard to determine where to place it on the reptile family tree, the scientists say.

As its fossils are relatively complete, scientists will likely have to unearth fossils of relatives – which are yet to be discovered – to better figure this out.

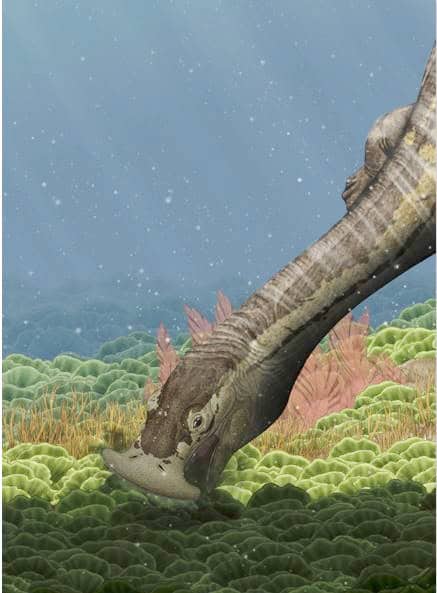

An artist’s depiction of A. unicus grazing on marine plants growing on a hard substrate in the eastern Tethyan Sea during Middle Triassic times. (Image: Science Advances. Credit: Y. Chen, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.)

An artist’s depiction of A. unicus grazing on marine plants growing on a hard substrate in the eastern Tethyan Sea during Middle Triassic times. (Image: Science Advances. Credit: Y. Chen, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.)

In the meantime, Atopodentatus appears to be most closely related to the plesiosaurs, the sea reptiles with typically long necks that were top of the food chain in dinosaur-era oceans.

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors wrote:

“The evidence indicates a novel feeding mechanism wherein the chisel-shaped teeth were used to scrape algae off the substrate, and the plant matter that was loosened was filtered from the water column through the more posteriorly positioned tooth mesh.”

“This is the oldest record of herbivory within marine reptiles.”

Citation: “The earliest herbivorous marine reptile and its remarkable jaw apparatus,” Nicholas C. Fraser, Li Chun and Olivier Rieppel. Science Advances, Vol 2 no 5 E1501659. 6 May 2016. DOI: 10.1126/sciedv.1501659.