When insects start eating and wounding a specific plant, it secretes sweet droplets which attract ants – the ants kill the plant-devouring insects and protect the plant, says a team of German scientists. In biology this is an example of ‘mutualism’, when two organisms of different species – in this case a plant and an ant – exist in a relationship in which each individual benefits from the activity of the other. The ant gets its sugar, while the plant gets protection from plant-eating insects.

Several plant species attract predators of herbivores by secreting nectar from extrafloral nectaries – specialized glands. Extrafloral nectaries provide a nutrient source to animal mutualists, which in turn provide antiherbivore protection.

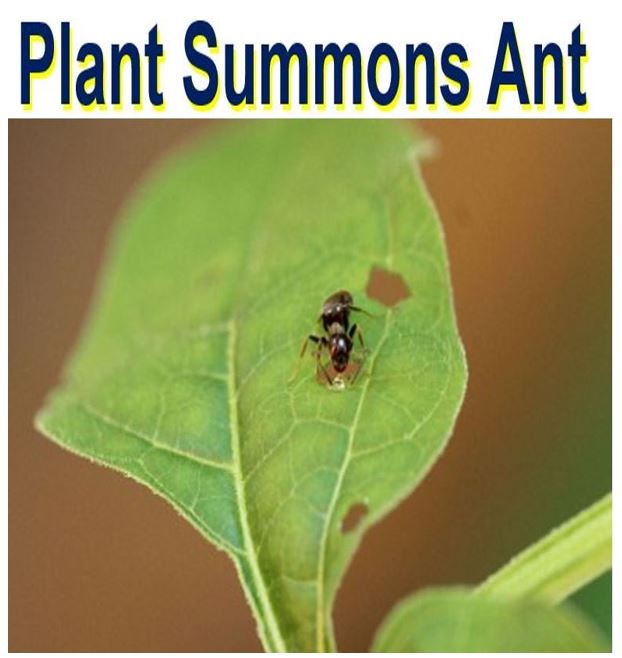

The plant secretes sweet droplets of water and sucrose, which the ants love. The ants come, consume the droplets, and also kill off some of the plant-eating insects. (Image: Tobias Lortzing)

The plant secretes sweet droplets of water and sucrose, which the ants love. The ants come, consume the droplets, and also kill off some of the plant-eating insects. (Image: Tobias Lortzing)

Nightshade has no nectar-producing glands

However, Solanum dulcamara (bittersweet nightshade), has no specialized nectar-producing glands, but still does this – secretes a sweet liquid that attracts ants – the researchers explained in the prestigious journal Nature Plants (citation below).

Prof. Dr. Anke Steppuhn, who works at the Free University’s Institute of Biology in Berlin, Germany, and colleagues found that sweet droplets ooze out from wounds anywhere on the nightshade when it is chewed into by herbivores.

The scientists are not sure how the plant secretes the sweet liquid. Perhaps it has a few sucrose-transporting proteins within the wounded tissue, they suggest.

The fluid is simply water and sucrose, not sap. In experiments carried out in a greenhouse, the researchers found that the secretions attracted three species of ants, which came and effectively patrolled the plants.

A common red ant attacking a flea beetle larva. These larvae feed on the young shoots of the bittwersweet nightshade. (Image: Tobias Lortzing)

A common red ant attacking a flea beetle larva. These larvae feed on the young shoots of the bittwersweet nightshade. (Image: Tobias Lortzing)

The scientists mimicked the secretions by placing drops of sucrose solution on wild plants. Ants were soon attracted to those plants, which experienced significantly less leaf damage compared to the control plants that were treated with just water.

The protection provided by the ants led to better plant growth and reduced predation by slugs, which are voracious plant-eaters that work their way through entire leaves.

Ants did not attack adult flea beetles

Adult flea beetles, however, which were responsible for most of the wounds on the plants, were not affected by the presence of ants. However, the flea beetle larvae were attacked and carried away by the ants. These bore into the pith of young shoots that sprout from the woody stem.

When an ant kills a beetle larva, it not only stops the damage that larva is causing to the plant, but also the destruction that would occur if it grew up to become an adult beetle.

The New Scientist quoted Prof. Steppuhn, who said:

“We’ve now observed that the plant, without any structure for secreting nectar, can use this kind of defence – which means that you do not need an organ.”

Botanists had long been mystified by the presence of extrafloral nectaries in several species of plants, which suggested that they had evolved independently several times.

Is this first step towards extrafloral nectaries?

Now that we know plants can secrete this nectar without specialized organs – it could be a common first step in evolution towards the emergence of nectaries outside flowers.

Prof. Steppuhn believes there are many more plants out there that bleed nectar to attract ants – we just need to look more carefully.

Therefore, if they are found on one plant, it generally means there are sap-sucking insects around that excrete sugar.

Prof. Steppuhn said:

“If none of those insects are found, we should search those plants for plant-derived nectar that attracts the ants.”

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors wrote:

“In greenhouse experiments, we reveal that ants can defend S. dulcamara from two of its native herbivores, slugs and flea beetle larvae.”

“Since nectar is defined by its ecological function as a sugary secretion involved in interactions with animals, such ‘plant bleeding’ could be a primitive mode of nectar secretion exemplifying an evolutionary origin of structured extrafloral nectaries.”

Citation: “Extrafloral nectar secretion from wounds of Solanum dulcamara,” Tobias Lortzing, Onno W. Calf, Marlene Böhlke, Jens Schwachtje, Joachim Kopka, Daniel Geuß, Susanne Kosanke, Nicole M. van Dam & Anke Steppuhn. Nature Plants. 25 April 2016. DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2016.56.