What is the Plaza Accord? Definition and meaning

The Plaza Accord was an agreement signed by the finance ministers of the G5 nations – the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, West Germany and France – on 22nd September, 1985, at the Plaza Hotel in New York City.

Some of the five countries – the largest economies in the world at the time – made specific pledges on economic policy:

- The USA promised to reduce its federal deficit, which had reached 3.5% of GDP (gross domestic product).

- Japan pledged a looser monetary policy.

- Germany said it would implement a series of tax cuts.

- They all wanted to see a better balance in between Japan’s imports and exports (exports were significantly higher).

The Plaza Accord, named after the Plaza Hotel in New York City, was signed by (from left to right) Gerhard Stoltenberg, Pierre Bérégovoy, James A. Baker, Nigel Lawson and Noboru Takeshita. (Image: Wikipedia)

The Plaza Accord, named after the Plaza Hotel in New York City, was signed by (from left to right) Gerhard Stoltenberg, Pierre Bérégovoy, James A. Baker, Nigel Lawson and Noboru Takeshita. (Image: Wikipedia)

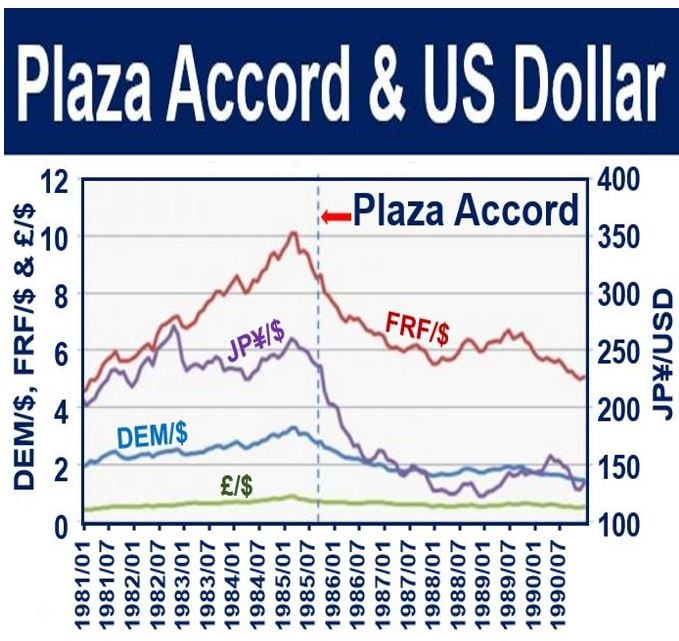

Plaza Accord and the US dollar

They all agreed that they would intervene in the currency markets whenever necessary to push down the US dollar.

Even though not all the promises were kept – the US federal deficit was never cut, and trade with Japan continued considerably in deficit – the Plaza agreement turned out to be a spectacular success.

Within two and-a-half years, by the end of 1987, the US dollar had declined by 54% against both the Japanese yen and German D-mark from its peak in February 1985.

From Plaza Accord to Louvre Accord

This steep drop triggered a new fear of a runaway free-falling dollar So, on 22nd February, 1987, the Louvre Accord was signed in Paris; the main objective being to stabilize the US currency.

The Plaza Accord was successful in its main objective – to bring down the value of the US dollar, especially in relation to the Japanese yen and the West German D-mark. (Image: data from businessinsider.com)

The Plaza Accord was successful in its main objective – to bring down the value of the US dollar, especially in relation to the Japanese yen and the West German D-mark. (Image: data from businessinsider.com)

In this second accord, the Italian and Canadian finance ministers were invited, Canada accepted but Italy declined the invitation. The US and Japan repeated the same federal deficit and monetary policy pledges.

In the Louvre Accord, the five nations promised to intervene if their currencies moved outside an agreed set of ranges – nobody outside that meeting knew what these limits were.

After the Louvre Accord, the dollar soon rose.

Plaza Accord bad for Japan?

For Japan, the signing of the Plaza Accord was significant in that it reflected the country’s emergence as an important player in managing the international monetary system.

However, the strong yen had recessionary effects on the country’s economy, which had for decades been export-dependent.

The Plaza Accord created an incentive for the expansionary monetary policies that eventually ended in the Japanese asset price bubble and **The Lost Decade that followed.

** The Lost Decade was the time following the asset price bubble’s collapse within the Japanese economy. The term refers to the 1991-2000 decade, but more recently has included the following ten-year period too – 2001 to 2010. Hence, the more recent term – The Lost 20 Years – is also used.

From 1995 to 2007, Japanese GDP fell to $4.36 trillion from $5.33 trillion, inflation remained at around zero percent, while real wages fell by approximately 5%.

Some journalists and economists have suggested that the Plaza Accord contributed to Japan’s asset price bubble and the two lost decades that followed.

In an article – The Case Against a New Plaza Accord – published by the Cato Institute, James A. Dorn wrote:

“The BOJ (Bank of Japan) sacrificed monetary stability for the sake of exchange rate intervention designed to stimulate the export sector. When the BOJ applied the brakes in mid-1989, money and credit growth dropped sharply, and asset prices collapsed in 1990.”

“Monetary disequilibrium continued to plague Japan-especially its financial sector-for the next decade.”

Video – The Plaza Accord – Definition and Meaning

This video explains why the US dollar appreciated so much against the D-mark and yen during the 1980s, which was great for Japanese and German exports, but bad for the US economy. The Plaza Accord was followed by a dollar depreciation.